In 1976, the cultural critic Raymond Williams published a volume titled “Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society.”

After Williams returned from World War II, says Sari Altschuler, associate professor of English at Northeastern University, he made the observation that “people were using the word ‘culture,’ and it didn’t mean what it meant before.”

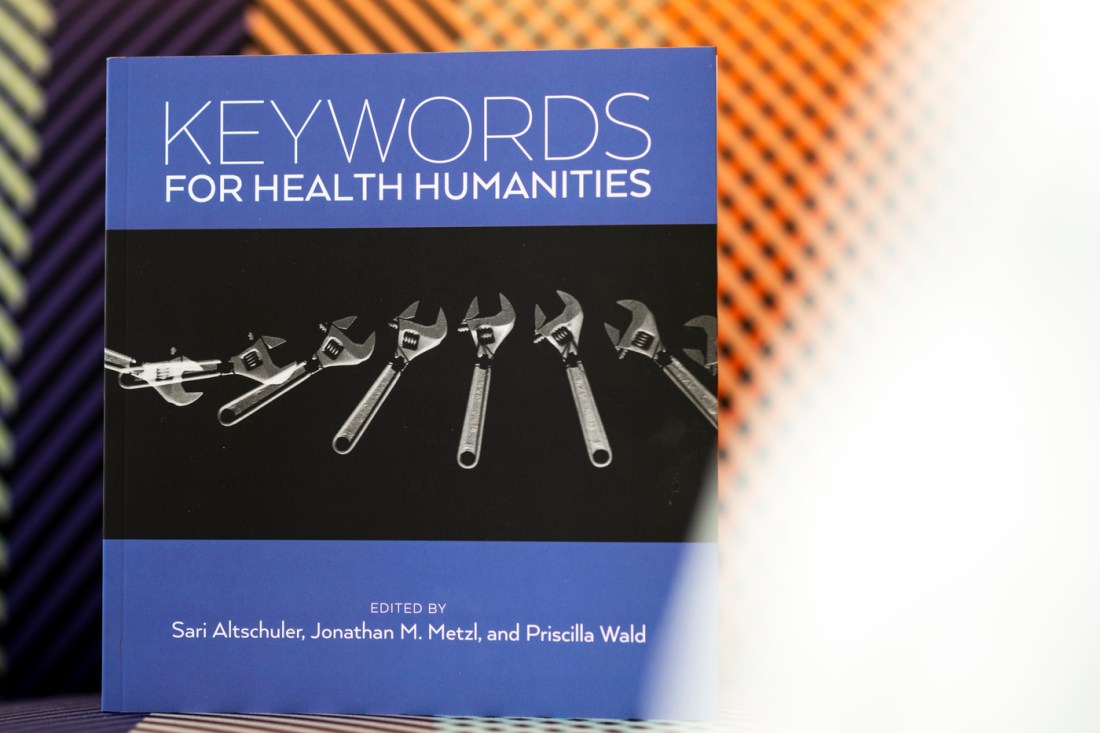

Williams’ intervention, his recognition that certain commonly used words are more fraught and complex than we often recognize — or might prefer them to be — is at the heart of Altschuler’s latest project, “Keywords for Health Humanities” (part of the NYU Press’s “Keywords” series).

Altschuler edited the volume alongside Jonathan M. Metzl of Vanderbilt University and Priscilla Wald of Duke University.

The textbook contains articles — each exploring an individual word related to the health humanities — written by over 70 leading scholars across disciplines in the humanities.

But these are neither dictionary definitions nor all-encompassing encyclopedia entries. Rather, Altschuler “would call them meditations on words and language as it changes, and has changed, historically,” she says, and “as it emerges in different, sometimes competing ways.”

For instance, one entry, written by Ed Cohen, professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Rutgers University, looks at “Chronic.” This entry is “a meditation on how time works in medicine,” Altschuler says. “What are the time periods that medicine can think with, and what are the time periods that medicine has difficulty with?”

“Chronic disease itself is quite a challenge for medicine, which tends to think about things in the acute,” she notes. “And if we can’t fix it, maintenance is more of a challenge for medicine.”

In opening up these words’ definitions and interlocking histories, Altschuler says that the articles are “meant to be provocations. They’re not meant to be comprehensive.”

Asked to define the field of “health humanities,” Altschuler says, with a laugh, that she actually wrote the article for that term in the volume. It needed an entry because “there’s a lot of creative misunderstanding about the word ‘humanities’ in the health humanities.”

“Doctors tend to use the word [‘humanities’] to confuse or conflate the arts and the humanities, and … to kind of describe things that they like rather than things that they have training in.”

But for Altschuler, “health humanities should really begin from the humanities themselves: as the study of human culture.”

“Keywords for Health Humanities,” then, is simultaneously a project of clarification — here are all the complicated meanings of a particular term — and complexification — yes, this term has a lot of complicated meanings.

“Part of the argument of the book,” she continues, “is taking seriously the humanities as ways of knowing, as disciplines that shed particular kinds of light and offer particular insights into health care.”

Altschuler also flags the provocation on “immunity,” written by Cristobal Silva of the University of California Los Angeles, as a good example.

“What does it mean,” Altschuler asks, “that ‘immunity’ began as a legal term? How does that help us think about how the concept of immunity works, how we think about what it means for a person to be immune?”

“These aren’t neutral, scientific terms.”

When Altschuler founded the Health, Humanities and Society minor and initiative at Northeastern, she faced a quandary as she developed its introductory course: she didn’t have the right kind of textbook.

“That’s part of the appeal of having these extremely short entries,” she says, “in non-jargony, layman’s terms. You certainly could use it to develop a whole humanities program.”

“Somebody might say, ‘Oh, that’s such a niche project. It’s based on this scholarly model that has to do with this cultural critic from England [Raymond Williams] in the ’70s or whatever.

“But actually, I think that a lot of professionals, especially in health care, [assume] that, when they’re using words, that everybody means the same thing by them.”

As “Keywords for Health Humanities” shows, that’s often not the case.

Altschuler doesn’t think that “Keywords for Health Humanities” will solve the problem of miscommunication — rather, she hopes it leads to further discussion among everyone from undergraduate students to health care professionals.

“I would love to see health care practitioners of all stripes picking it up,” she says. “Maybe they want to think a little differently about things that have seemed very simple to them, words that they use every day [but which] have more complicated histories than they might imagine, and are actually really historically specific.”

Altschuler says that “Keywords for Health Humanities” invites its readers to ask questions like, “How can I think differently about death? How can I think differently about memory or harm?” and, “How do we bring the person back into health care?”

Health care, she says, “should be about care. It should begin from one person really listening to another, and we should strive to understand each other as best we can.”

“The words are meant to be provocations in that way, too.”

Noah Lloyd is the assistant editor for research at Northeastern Global News and NGN Research. Email him at n.lloyd@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter at @noahghola.