Frank Lloyd Wright may be the most famous architect of the 20th century, but Amanda Lawrence says that even he shouldn’t be considered a singular genius — or even, necessarily, that original.

Lawrence, an associate professor of architecture at Northeastern University, has published a new book, “The Architecture of Influence: The Myth of Originality in the Twentieth Century,” which argues that no architectural work is truly original — but also that this isn’t a bad thing.

Unoriginality is “really the basis of a creative practice, which I think is at the core of architecture,” Lawrence says. “I think ‘unoriginality’ has a negative connotation that is actually unnecessary and inaccurate.”

Booklaunch recently announced the shortlists for the 2024 Architectural Book Awards, which included “The Architecture of Influence” in its Architectural Treatise of the Year category.

An Ancient Greek temple in Tennessee

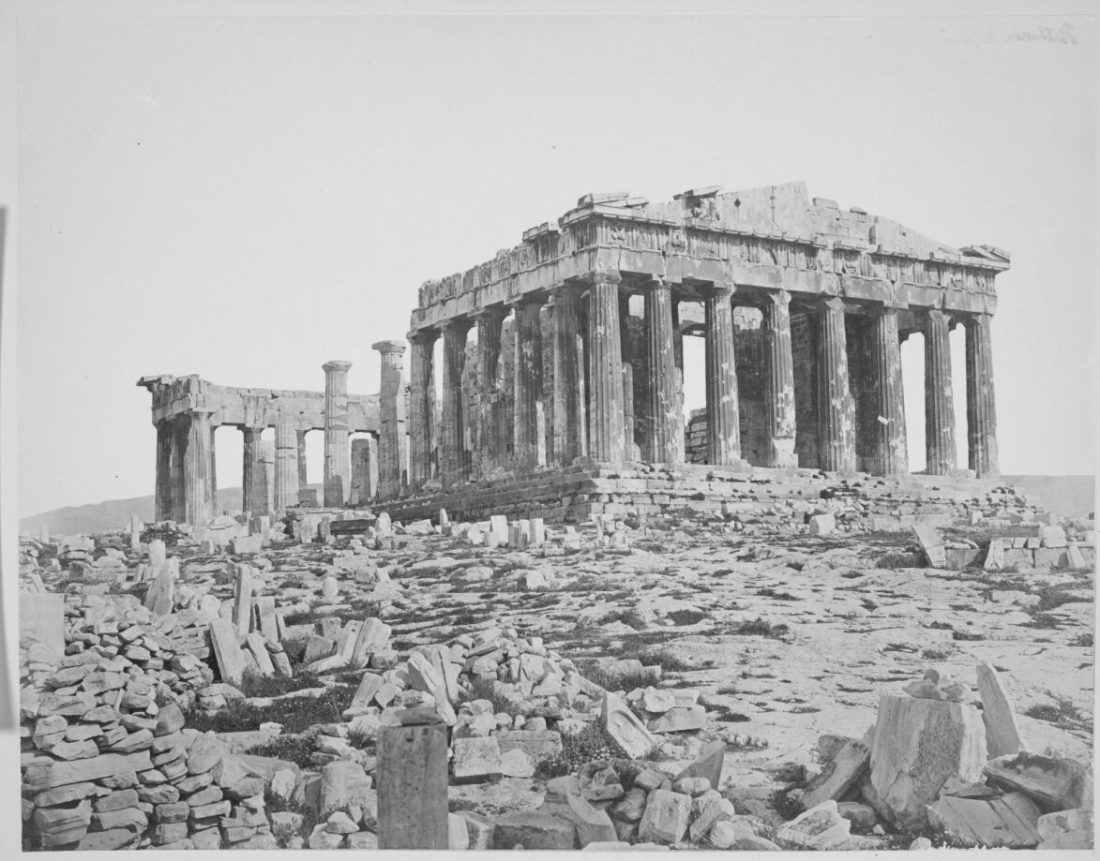

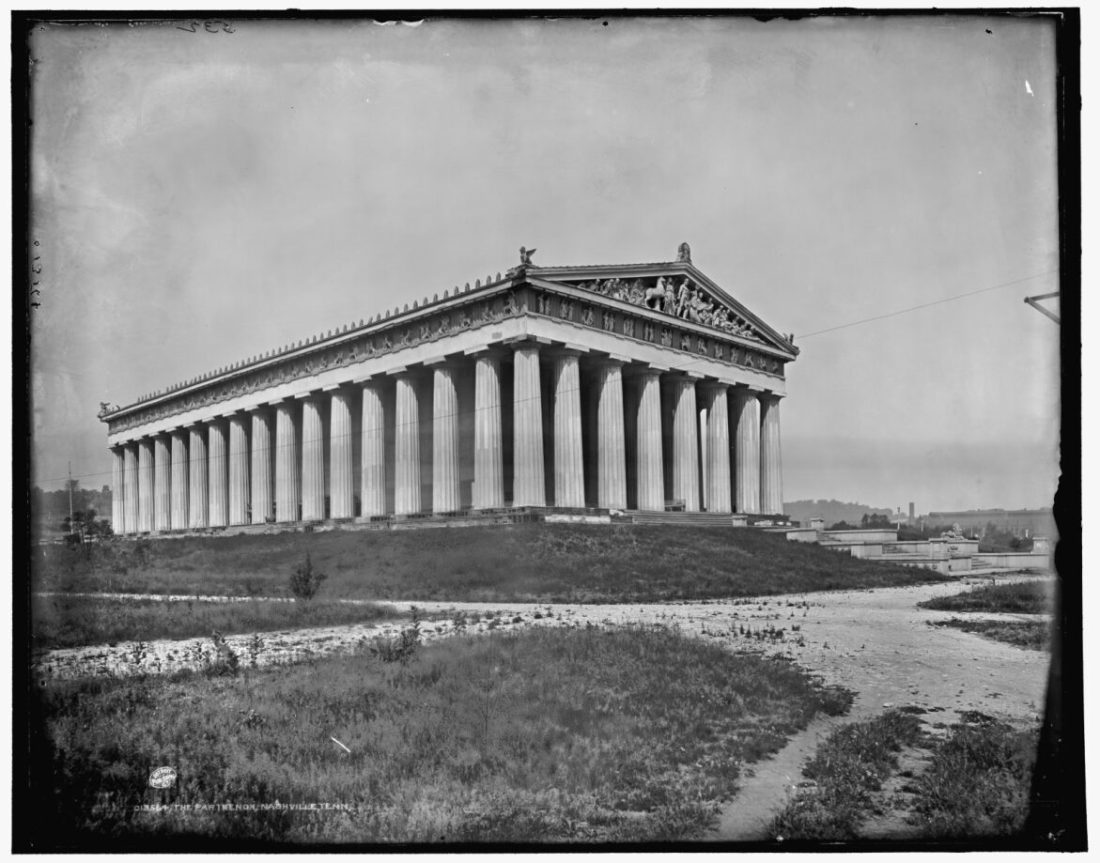

One example Lawrence provides is the Nashville Parthenon, an exacting replica of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, but located in Nashville, Tennessee.

The replica was built as part of the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition, an event modeled on the world’s fairs of the period, where organizers and architects “would often reproduce works of architecture from around the world,” Lawrence says.

In this case, a copy — a one-for-one duplication — became a source of innovation.

In its first iteration, Lawrence says, the Nashville Parthenon was constructed out of plaster, but “it was so popular [they decided], ‘Oh, well, we want to keep this.’” But because they couldn’t afford to use the materials of the original in Athens — marble — they instead went with concrete.

“The architects and engineers developed a special method using rose-colored bits of aggregate, so they could simulate the color of the marble in Athens,” Lawrence says.

Often, reproductions like the Nashville Parthenon are “seen as kind of silly,” Lawrence says, “because they’re not ‘real architecture.’ They’re not seen as producing anything new.”

But, in this case, the effort of producing the replica led to “all this technological innovation that went into the making.”

To turn the supposed authority of originals even more on its head, Lawrence then points out that, because the replica Parthenon was so precise and based on so much research, when there were debates about rebuilding the original, ruined structure in Athens, proponents of the rebuild looked to Nashville for their designs.

“So then you get this kind of inversion where the copy becomes the original,” Lawrence says. “The replica becomes the thing that they are looking to as the ‘source.’”

While the Nashville Parthenon might be an extreme example of one building duplicating another, “The Architecture of Influence” highlights many ways that existing buildings reference prior models and change our understanding of them.

“The book is organized by what I would call influence ‘types,’” Lawrence says, broken into seven chapters covering “Replicas, Copies, Compilations, Generalizations, Revivals, Emulations and Self-Repetitions,” according to the publisher’s webpage.

Frank Lloyd Wright and the unoriginality of genius

In thinking about architecture as a set of reinterpretations, Lawrence says that it’s also important to challenge the concept of the “genius.”

Take Frank Lloyd Wright. “He often would deny any influences,” Lawrence says. Part of the work of “The Architecture of Influence” is to “interrogate that concept of the genius and actually debunk it.”

Lawrence highlights two Austrian architects who worked under Wright, Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra. “Both architects emulated Wright, but also made their own contributions to his projects.”

During one of Wright’s extended travels, Schindler “oversaw the work in Wright’s office, and there’s correspondence back and forth where [Schindler] says, ‘Okay, but I’m doing all the work,’ and Frank Lloyd Wright says, ‘Yes, but you know — you’re just doing me,’” Lawrence pantomimes.

“Which brings up an interesting question of signature, and what defines a Schindler or a Wright project anyway?”

So while Frank Lloyd Wright “embodies the myth of the genius,” Lawrence says, by complicating that myth, scholars can suddenly “see all the other voices that went into the making of things.”

“When we talk about geniuses,” she says, “the next word is always, ‘inventive,’ ‘original,’ ‘innovative.’” Debunking the idea of the genius provides “a different set of ideas through which we look at architecture—ideas like accommodation, rearrangement and imitation.”

Considering architectural works within their historical contexts can radically change the conversation. “Not only is every new work inevitably borrowing from the past,” Lawrence says, “it’s also informing and changing our conception of that past that it references.”

Rather than any one project standing on its own, all architects are in conversation with their predecessors, Lawrence says, “reworking the past” into new forms that may eventually be reworked themselves, creating “a kind of conversation with earlier previous works.”

“The Architecture of Influence” provides “hopefully new interpretations,” she says, “new ways of seeing works that we thought that we knew.”

“That’s how ideas work, right?” Lawrence continues. This conversation between the past and present is “ultimately how fields move forward and advance.”