This data visualization from Northeastern University researchers helps make sense of the Democratic presidential debates in real time

Who will challenge President Donald Trump in the 2020 election?

Nick Beauchamp, an assistant professor of political science at Northeastern. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

The 10 Democrats who participated in the latest debate Thursday in Houston revealed a variety of strategies. Julian Castro took on frontrunner Joe Biden. Andrew Yang separated himself from his rivals by offering prizes of $1,000 a month to 10 people. Leading progressives Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders dueled over the same turf without openly attacking one another.

What does all of it mean as the candidates zero-in on the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary five months away?

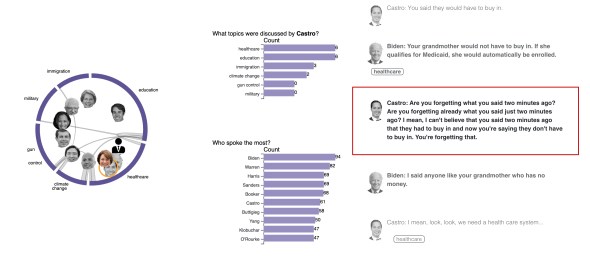

The subjects addressed in the debate help to reveal the candidates’ strategies, says Nick Beauchamp, an assistant professor of political science at Northeastern, who has joined with Laura South, a doctoral candidate in data visualization, to develop a real-time analysis of the debate as the candidates are speaking.

“You can see the top four candidates dynamically moving through the space of words, with occasional zaps between them when they attack each other—amusingly looking like a video game,” Beauchamp says of the visualization tool.

Beauchamp, who specializes in quantitative text analysis, pinpointed the key issues of the debate for News@Northeastern.

Based on what we’ve seen from the two rounds of debates thus far, have the key issues of the Democratic campaign emerged?

Based on recent polling (scroll down to the 10:09 p.m. post), Democrats are most concerned with beating Trump (40%), the economy and inequality (16%), healthcare (10%), climate change (8%), and guns (4%).

Based on the data collected by Laura South and a team I’ve worked with, in this debate the candidates spoke most on healthcare, education, guns, military and foreign policy, immigration, and climate change, in that order. So beating Trump got relatively shorter shrift—understandable, since everyone mostly agrees on the need to beat him—as did the economy and inequality, which got very little attention in this debate, though more so in previous debates.

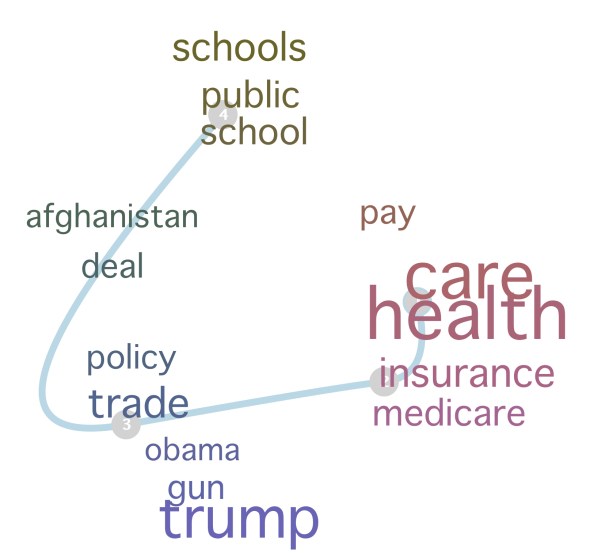

You can also see the top issues via a Plotmap and a dynamic visualization that I did:

Courtesy of Nick Beauchamp.

The Plotmap shows the overall trajectory of the debate, starting with the first quarter (the circle with a 1 in it, slightly obscured) and ending with the fourth (circle with a 4 in it), where the words closest to each segment are the terms most prevalent at that stage of the debate.

Note how the debate begins in healthcare, moves into segments on trade, immigration, and guns (which also involve more references to Trump and Obama), then onto foreign policy and war, and finishes with education. Note also that “pay,” one of the few explicitly economic terms and a point of contention between the center and left, recurs in both the healthcare and education segments.

What do you make of the tension facing Democratic candidates who are united in their ambition to defeat Donald Trump, but first must criticize and defeat each other en route to the nomination? As a matter of perspective, do you find this group of competing candidates to be relatively civil in their criticism of each other because of their shared urgency to beat Trump?

I’m not sure that the urgency to beat Trump to the exclusion of all else is as equally shared among the candidates as many people think. For instance, I was reading the cross-tabs on a recent CNN poll and noticed that one of the questions asked respondents whether they preferred a candidate who had a better ability to beat Trump or a candidate with whom they shared policy preferences. The interesting results were:

The upshot is that white people, women, the college-educated, and the wealthier are much more interested in beating Trump relative to non-white people, men, non-college educated, and the less wealthy, who emphasize policy positions more, though they still want to beat Trump too. Since these demographic groups also support the candidates differently, this suggests that the candidates themselves might be incentivized differently in terms of time spent attacking Trump vs. taking other positions.

In this debate, the candidates differed quite a lot in mentioning Trump (scroll down to the 10:58 p.m. post), with Harris at 11 mentions, Sanders at five, and Biden and Warren at only one each. While they all agree that beating Trump is the ultimate goal, the candidates and the public do seem to vary in how highly they emphasize that goal in the short term.

There is also a strategic element. In most of these debates, the only thing that has hurt Biden in the polls has been attacks from other Democrats (for example, Harris’s attack in June). So it is in Biden’s best interest to focus on unity topics: not just Trump, but other areas where Democrats somewhat agree (or at least don’t disagree too loudly), such as foreign policy, guns, and possibly immigration. Every minute spent attacking Trump or the status quo is a minute Biden avoids another potentially damaging hit.

There is a definite asymmetry between the candidates in terms of who wants to focus on Trump and unity vs. highlighting contrasts between the candidates. So we got a relatively uncivil though highly interactive segment on healthcare, followed by longer stretches of civility and non-interaction apart from an occasional jab.

In the end, apart from that feisty start, it was a relatively civil debate, which is perhaps not the best move strategically for Warren, Sanders or Harris. But it’s also hard to shift the discourse from what the moderators lay out without engaging in jabs like Castro did against Biden, which have a high risk of backfiring.

We are very early in the campaign. Do you have a sense for which outsiders may rise to challenge the poll leaders Biden, Warren, and Sanders?

It’s no longer quite so early. The Iowa caucus is February 3, and New Hampshire is February 11, only a few months away now. Biden has maintained a steady lead at around 30% for almost a year now, and Sanders has been similarly steady at around 15 to 20%. The only real change has been Warren shifting from single digits to somewhere in the 15 to 20% range, and Harris’s brief excursion up and then back down.

So things have been pretty stable, far more so than the 2016 Republican primary or the even more volatile 2012 Republican primary. And similarly, for all of the turmoil of the past couple years, Trump’s own approval has been remarkably stable. So while the betting markets appear a bit more volatile, with Warren recently taking the lead, overall things look pretty stable absent some major event.

I think it’s more likely that one of the front-runners stumbles and loses ground than one of the outsiders has a dramatic rise—but on the other hand, if I’ve learned anything from a grant I’m using to study forecasting, it’s that it’s a mug’s game making predictions.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.