The Thames gives up centuries of history to Northeastern mudlarkers

The immersive experiences of mudlarking and a migration-themed walking tour forms a core part of the London: Literature, Culture, Identity course.

LONDON — There is 2,000 years of history lying underneath the London asphalt. But there is no digging required to get your hands on a piece of it.

As Northeastern University students scoured the muddy banks of the River Thames during their mudlarking experience, they discovered centuries of London life at the tips of their fingers.

After an hour of scavenging under Millenium Bridge, in the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral and with Shakespeare’s The Globe theatre and the Tate Modern — a former coal power station turned art gallery — opposite, their finds gave clues to British history going back a millennium.

In their clear plastic bags were shards of medieval pottery, handmade Tudor crockery and clay tobacco pipes. Not all discoveries were as desirable as others — animal bones and sheep’s teeth were quickly put back.

Looking at her collection, Jenny Gardiner, an English major from Stroud, south-west England, said she was surprised at how accessible the treasures were. “It’s really fascinating because I didn’t think there would be much on the floor but then as we were walking, we looked down and there was stuff everywhere, which was really cool,” said the third-year student.

The Thames Explorer Trust led two mudlarking sessions as part of the London: Literature, Culture, Identity course, led by Charlotte Grant, an associate professor in English. As well as mudlarking, the course also involves a walking tour guided by the Migration Museum. They are then asked to put together their own tour experience based on written works that explore the topics of migration and identity.

Mudlarking, the practice of scavenging for artefacts on the beds of tidal rivers, has been a pastime for hundreds of years in London, explained Chris Webb, a freelance educator with the trust. In the 19th century, it was mostly carried out by the city’s poorest as they searched near docked cargo ships for items to sell but it continues to hold appeal.

Even today, the Thames still gives up items from the past that it has held onto for centuries. Webb said that on the south side of the river by The Globe, a replica of Shakespeare’s most famous playhouse, a bear claw had been found — a gruesome reminder of the days of bear-baiting and other animal cruelty.

Webb said mudlarking had grown in popularity because it was able to bring history to life. The Port of London Authority introduced permits in 2016 but has since suspended issuing new licences after the waiting list reached 10,000 people.

“You go to a museum and sometimes they’ve got a handling collection, but a lot of it might be replicas,” said Webb. “I’m still amazed that this stuff, thousands of years of history, just sits here.”

Grant, co-editor of the book “Cultures of London: Legacies of Migration”, said mudlarking was a “great way of demonstrating the multi-layered history of London in a very practical way.”

“I wanted to give students an experience that they wouldn’t necessarily have had and to shake up the way we think about history, objects and material culture,” she said.

Grant tasked her class with writing about one of their mud-coated finds. Gardiner said she planned to use a clay pipe she discovered to explore the origins of tobacco in northern Europe. “I would be interested to look at tobacco coming over to the U.K. and the enlargement of the tobacco pipes as the tobacco became cheaper,” she explained.

Clay pipes were previously sold with pre-packaged tobacco and thousands of them have been discovered in the river. Webb, when briefing the students about what they might find on the riverbed, said they would be able to tell when a clay pipe dated from by inspecting its size. Smaller examples were likely older due to tobacco being more expensive when first imported in the 1580s, but as it arrived in larger quantities and became cheaper towards the 1700s, the pipes grew larger as a result.

A week after mudlarking, the class reassembled for another study visit, this time to learn about the history of the area surrounding Northeastern’s One Portsoken building. Their guide, Liberty Melly, head of learning at the Migration Museum, said the tour was about “telling the rich and diverse history that has brought us all together”.

Editor’s Picks

The students were taken to the Roman wall in Vine Street, situated yards from their classrooms, and told about the origins of America Square, a block away. Melly told the group that the name was chosen in the 18th century as a dedication to the American colonies, reflecting their pre-independence importance to Britain in terms of trade.

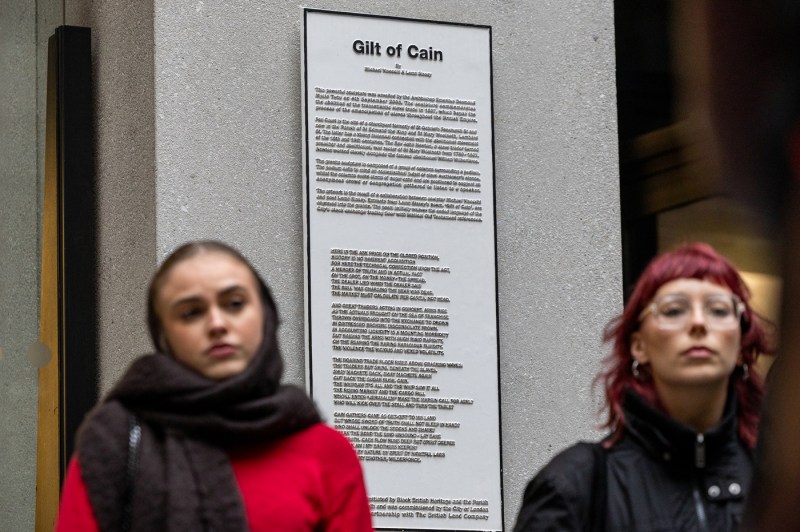

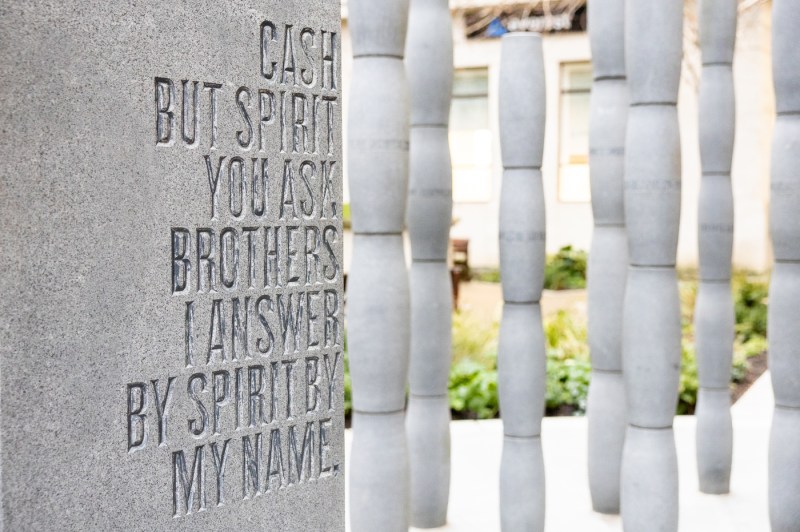

Melly also took them to the Gilt of Cain, a “hidden” sculpture and poem that was commissioned to commemorate 200 years since Britain passed a law abolishing the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

“The wealth that was generated by slavery underpinned the City of London,” she told them.

Anastasia Riches, a third-year politics and international relations student from Lisbon, said she felt the tour had helped her consider how her own tour route would work. She is planning to put together an experience that will take participants through the story of the Bangladeshi migrant community in Whitechapel, east London.

“I found it really informative in terms of how we’re meant to present our project, in the way that we would establish a storyline through a certain section of London,” Riches said.

Grant said the course is designed to provide the students with “enhanced” research, presentation and communications skills, along with “a new sense of how we present history and heritage.”

As part of the tour aspect of the course, Grant also arranged for Odile Jordan, a history Ph.D. student and research assistant with Northeastern’s Mapping Black London project, to give a talk on how to find materials in archives.

“This is hopefully something that will fire students’ own interests,” continued Grant, “and they can do work that is meaningful to them. Or, conversely, just learn about something they know nothing about.”