This adaptive splint could transform autism care

Northeastern researchers are developing a new splint that can relax and stiffen on command.

In the summer of 2024, Northeastern University professor Matthew Goodwin invited a small group of colleagues on a trip to the Marcus Autism Center in Atlanta with a simple goal.

For quite a while now, Goodwin has been frustrated by a lack of tailor-made garments designed to keep individuals with severe autism, also known as profound autism, from hitting themselves or others when they exhibit self-injurious behavior.

The options available resemble riot gear — hockey pads, football helmets and mixed martial arts equipment, he said.

“They’re very scary looking and stigmatizing,” said Goodwin, who is jointly appointed in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences and the Khoury College of Computer Sciences and conducts research regularly in collaboration with the Marcus Autism Center.

So, Goodwin assembled a team of Northeastern researchers to help him solve the problem, meeting directly with the Marcus Autism Center’s staff to understand the issue and develop a plan forward.

Now, that group, backed by the National Science Foundation, is developing an adaptive splint designed for autistic patients to address that issue head-on.

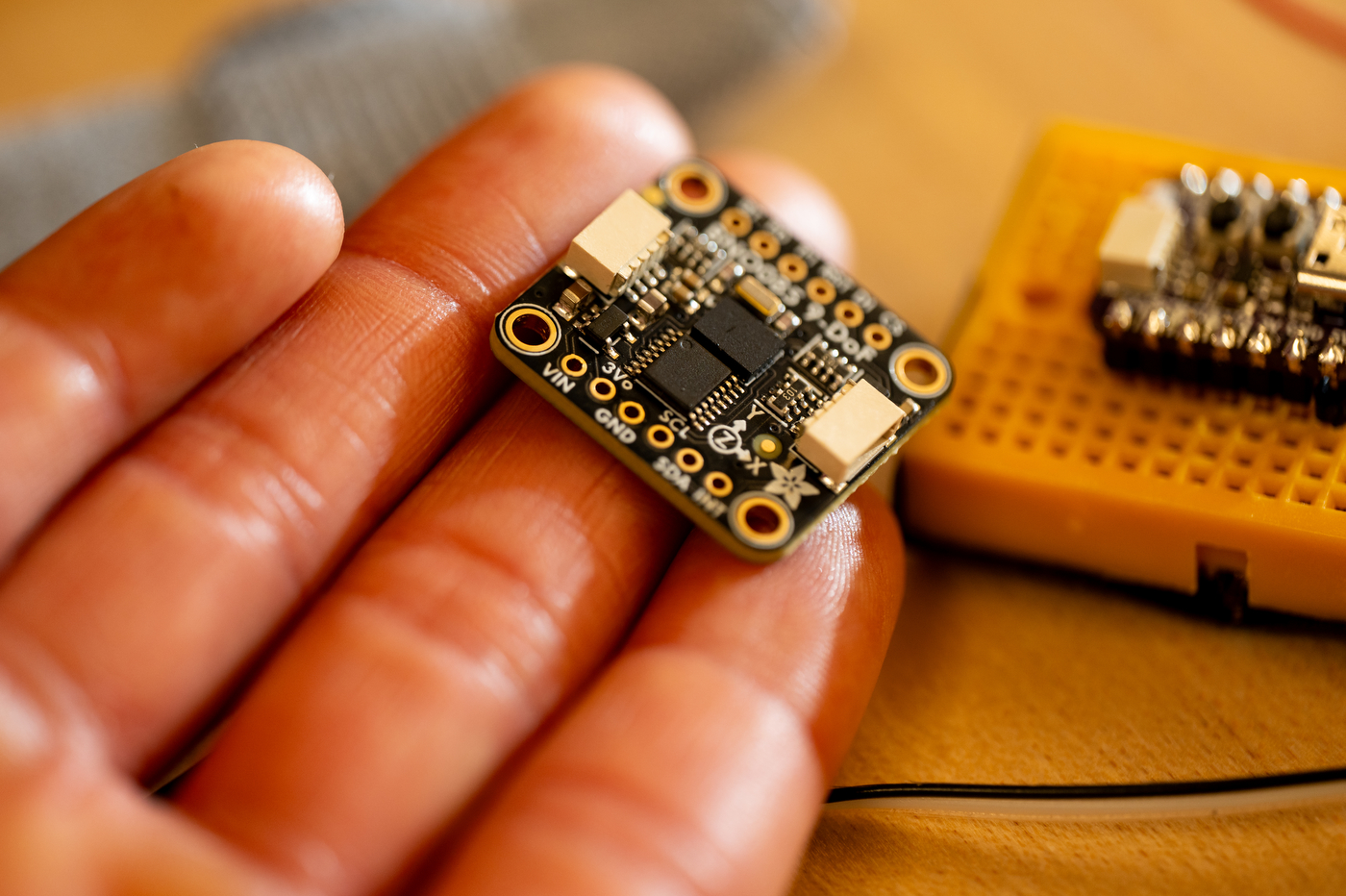

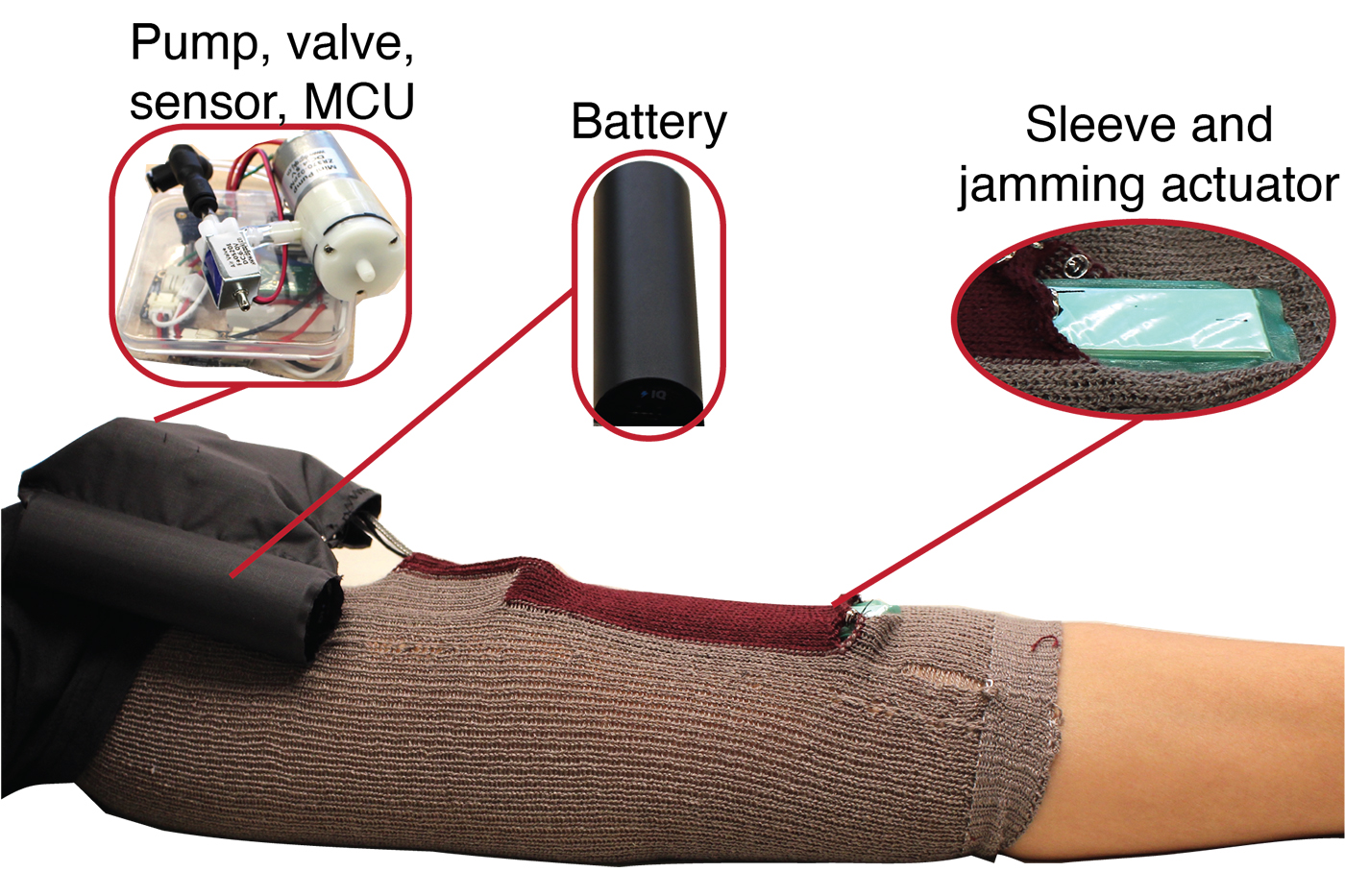

Taking advantage of a range of sensors, actuators and soft robotics technology, the splint’s key feature will be its ability to relax and stiffen on command, said Kris Dorsey, a Northeastern professor in the College of Engineering and Bouvé College of Health Sciences and the principal researcher on the project.

The splint will be placed on an autistic patient’s arm and used during certain medical exercises, particularly during times when patients may exhibit self-injurious behavior, she explained.

Dorsey visited the center with Goodwin, alongside Megan Hofmann, a professor in the Khoury College of Computer Sciences and the College of Engineering, and Aston McCullough, a professor in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences.

All four are now collaborating on the project, each bringing their own area of expertise to the undertaking. Dorsey is leading and specializing on the soft robotics side; Hofmann, the specialized materials; McCullough, the kinematics and video data; and Goodwin, the physiology and motion-sensing technology.

But the researchers aren’t starting from scratch. This work builds on a previous splint Dorsey developed with Hofmann this year.

“We’re going to be making the entire system more robust, easier to use, to sense where the wearer’s elbow is to make it something that’s useful for clinical deployment,” she said.

Unlocking a new level of therapy

This new splint will be key for behavioral therapy, particularly for registered behavior technicians, or RBTs, who work closely with these populations, said Goodwin.

The biggest benefit of the splint for RBTs is that they will be able to relax and stiffen it to help reshape the autistic individual’s behavior, he said.

One standard method that RBTs use to determine the source of an autistic person’s aggression is a protocol called a functional analysis of behavior. It deliberately involves evoking a child to act out, Goodwin explained.

That might call for putting a child in a crowded room or in a situation without their favorite toy.

The goal of that exercise is to determine whether their behavior is either socially driven, meaning they want other people to behave a certain way, or an “automatically maintained behavior,” meaning it is not socially driven and meant to influence others.

That type of situation can put an RBT and the patient in harm’s way. The researchers’ splint could help make that situation safer for both, Goodwin said.

Editor’s Picks

The splint could also be used to collect valuable biological sensing data — like cardiovascular information — that could be used to predict when and why people might start to get aggressive.

Northeastern is working in tandem with the Marcus Autism Center, which is a part of Emory University, on the three-year project, Dorsey said.

“We are so excited about this collaboration with Northeastern,” said Dr. Mindy Scheithauer, a psychologist at the Marcus Autism Center. “(Professor) Dorsey and her team have seen the high needs of these kids and their families and are dedicated to using cutting-edge technology to improve their quality of life. The concept of splints that can be worn in a loose state that does not impede range of motion but can be made rigid enough to keep the child safe is truly groundbreaking and would be a game changer for these kids.”

The team will spend year one building the hardware. During the second year, the team will work closely with the RBTs to make sure the splint fits the clinic’s needs.

“Is the battery long enough? Is it going to withstand someone dropping it? If we need to wash it, how do we do that? Answering those user-centric questions” are important,” Dorsey said.

Year three will involve actually testing the splint in clinical settings and behavioral therapy sessions.

This type of therapy is often hard to find and not many clinics offer it, Dorsey explained. Many families are on wait lists for years before they get to be seen. The hope is that the adaptive splint will make treatment more accessible for those who need it.

“Our ultimate goal beyond this project is to make this type of behavioral therapy more efficient, which will help more individuals access this type of care,” she said.