Americans and Canadians agree: More AI training is critical to combat job loss

Findings from a multi-year study show that many adults in the U.S. and Canada want the government to address AI-related job loss through workplace retraining and reskilling — a solution that cuts across party lines.

As fears of artificial intelligence-fueled job loss ripple through society, one potential fix is seeing broad support from Americans and Canadians alike: giving workers the right skills to thrive in the AI age.

A multiyear study, highlighted in a recent Foreign Affairs article, reveals that many adults in the U.S. and Canada want the government to address AI-related job loss through workplace retraining and reskilling — a solution that cuts across party lines and far and away trumps other proposed alternatives.

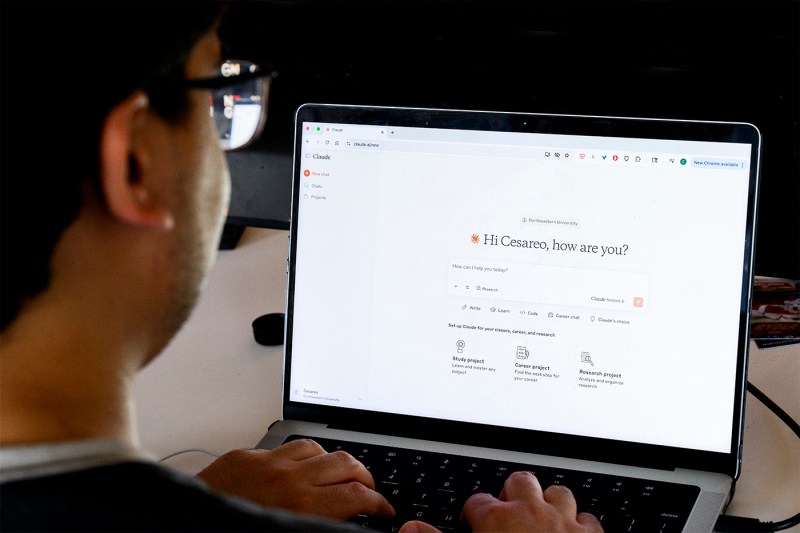

The researchers surveyed 6,000 Americans and Canadians, randomly presenting them with different economic shock scenarios involving either AI adoption or offshoring, and then asked them to evaluate a range of potential policy responses. Beatrice Magistro, an assistant professor of AI governance at Northeastern University, and her colleagues analyzed the results to compare how attitudes varied across the two types of disruption and identify which policies drew the most support.

“We tried to understand what their attitudes and opinions toward generative AI were and what the political consequences might be,” says Magistro, who co-wrote the Foreign Affairs article titled “The Coming AI Backlash.”

It turns out, regardless of which political party they belonged to, respondents in both countries ranked worker retraining as their top policy choice. Greater regulatory oversight was the second-most popular policy, which also saw support across the political spectrum, followed by expanded safety nets.

Support for retraining programs — initiatives that have proliferated across higher education and the private sector — makes sense on paper: some data shows that they can boost earnings among displaced workers entering new occupations. Those initiatives can include a wide range of programs — from self-guided learning and free online courses or tutorials, to online degree programs and employer-sponsored boot camps or other kinds of immersive trainings.

Experts note that the concept is often used interchangeably with “reskilling.”

“The trick to staying relevant in the labor market has always been to keep re-skilling and AI is no different except that the pace is much more rapid than what we have seen when other transformative and disruptive technologies have been introduced, like personal computers, the internet, 3D printing and cloud services,” says Alicia Modestino, associate professor of public policy and urban affairs and economics at Northeastern and research director of the summer jobs program.

Other solutions to AI-driven changes, Modestino notes, lie with “apprenticeships, co-ops, and other subsidized educational opportunities could help preserve future talent pipelines.”

Of course, not all sectors face immediate AI job loss. Industries like health care, skilled trades, management, and emergency services tend to be less exposed — due to less automation — than fields such as legal services and media.

Editor’s Picks

“There is a lot of discussion about what we mean by retraining,” Magistro says. “Does it mean to teach people to use artificial intelligence, or to train people to work in less AI-exposed sectors?”

Aside from solutions, the survey gathered a lot of data about how people feel about the technology more broadly.

Based on how participants responded to the more than 81 scenarios put to them, Magistro says they tended to fall into two groups: complementers and substituters. Complementers believe AI will enhance workers’ skills, create new jobs, and drive lower prices and higher wages. Substituters take the opposite view — that AI will replace human workers and worsen economic conditions.

“What’s interesting is that these two groups of people have very different policy and political preferences,” she says.

Broadly speaking, complementers are more likely to favor policies such as reskilling, education programs or social insurance. Substituters are more likely to favor immigration restrictions and measures such as robot taxes, which penalize companies that replace humans.

Based on those preferences, Magistro says complementers tend to lean liberal, while substituters skew more conservative. But she notes that political attitudes toward AI are far from fixed.

“Public attitudes on AI are still very malleable, so they’re definitely changing,” she says.

Other data paint a similarly complicated picture. Recent research from the multiuniversity Civic Health and Institutions Project (CHIP50) finds that views on regulating AI don’t follow typical red-blue state lines, and concerns about workplace disruption are widespread.

President Donald Trump has embraced the AI revolution not only in an effort to spur innovation and transform the workforce, but also to hedge against Chinese advances in the tech space. Billionaire Elon Musk, who once led Trump’s cost-cutting Department of Government Efficiency, has also leveraged artificial intelligence in numerous ways — including to develop his own widely used chatbot, Grok.

Magistro says political attitudes toward AI will play a significant role as the administration ramps up investment in the technology and as legislation takes shape in statehouses across the country.