Researchers decode the chemistry behind a deadly genetic disorder

Northeastern researchers used AI to predict which genetic mutations cause OTC deficiency, uncovering clues to guide future treatments.

Northeastern University researchers used an original machine learning tool to predict how genetic mutations cause a rare metabolic disease known as OTC deficiency, uncovering some underlying biochemical mechanisms at play and laying the groundwork for future treatments.

Ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency is a genetic disorder that impairs the body’s ability to safely eliminate ammonia, a byproduct of the normal recycling of proteins that happens in cells. Ammonia buildup can be toxic and can lead to serious harm, including brain or liver damage and even death.

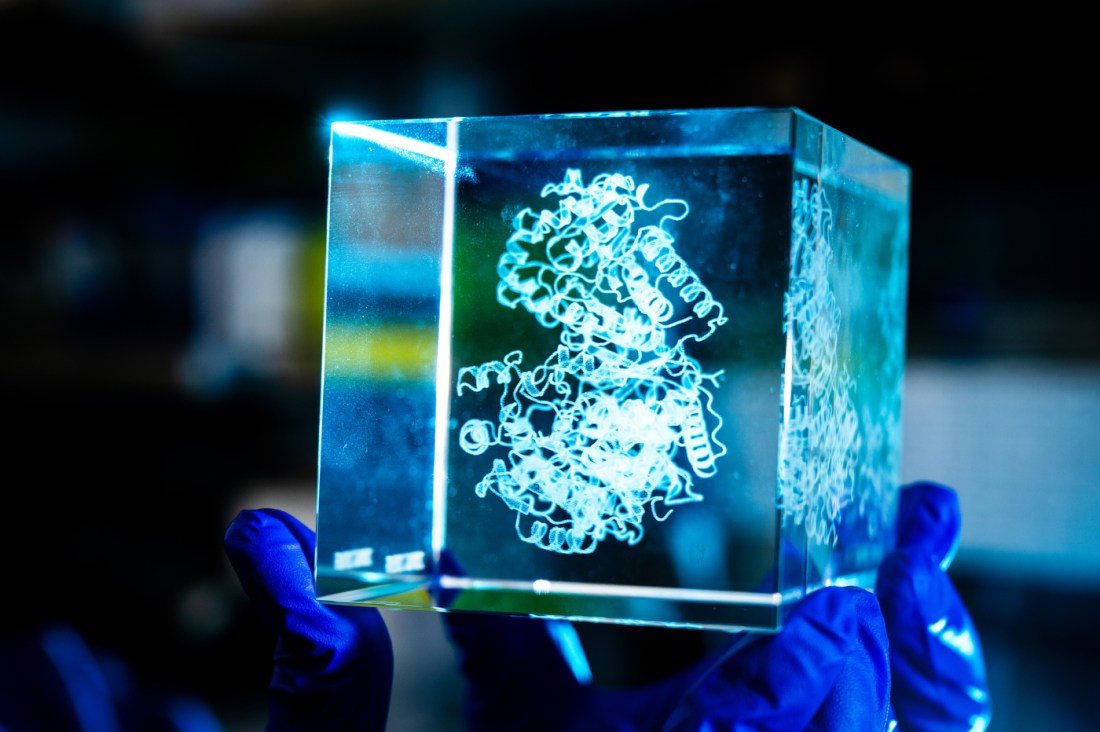

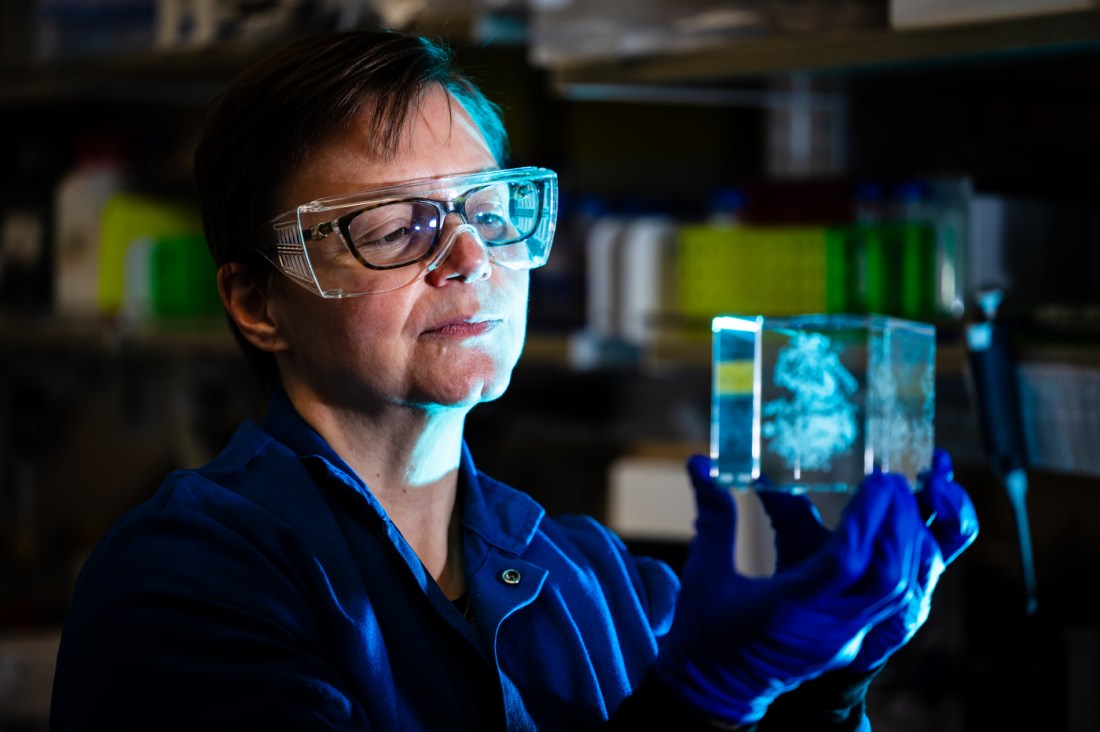

A research team led by Northeastern professors of chemistry and chemical biology Mary Jo Ondrechen and Penny Beuning combined their original machine learning tool, called Partial Order Optimum Likelihood, or POOL, with biochemical laboratory experiments to study dozens of mutations in the OTC gene. This gene produces the OTC enzyme — a protein that accelerates chemical reactions — which is part of the cycle that converts nitrogen into urea so the body can excrete it in urine.

“Professor Ondrechen’s machine learning method is extremely good at predicting the effects of mutations on the function of a protein,” Beuning says. “This is the second time we used this method to analyze hundreds of mutations in an enzyme that is associated with a disease, and the experimental analysis in both cases showed that the predictions were accurate.”

The study sheds light on how certain mutations disrupt the enzyme’s normal activity. This deeper, molecular-level understanding of disease mechanisms is an important step toward developing personalized treatments in the future.

“Right now we’re asking fundamentally, ‘Why is this mutation bad? Why is it causing disease?’” Ondrechen says. “And then you could try to think of a drug, a small molecule that would bind to the protein and counteract the effect of the mutation.”

Every year, between 14,000 to 77,000 individuals are diagnosed with OTC deficiency. A severe form of the disorder affects some newborns — typically boys — shortly after birth. A milder form of the disorder can appear later in childhood or adulthood.

“Here in Massachusetts, every baby is tested for a variety of inherited mutations, including OTC deficiency,” Ondrechen says.

Symptoms vary in severity but can include vomiting, fatigue, seizures, developmental delays, and psychiatric issues. Current treatments focus on managing ammonia levels through a low-protein diet, medications that remove excess nitrogen and, in severe cases, liver transplants.

The Human Gene Mutation Database reports 486 known mutations in the OTC gene. Of those, 332 involve a change in just one building block of DNA and can weaken or completely disable the enzyme.

“It is also possible that only some of the mutations actually reduce the activity of the enzyme,” Beuning says. “Some of them will arise randomly and not be associated with disease, even though they are found in a person’s cells.”

In their experiments, the researchers discovered something unexpected: some mutations linked to disease behaved normally in test-tube experiments but became impaired when tested in living cells.

The researchers focused on specific amino acids in the enzyme that can switch their electrical charge on or off — a property that enables the protein to catalyze chemical reactions. They computed a measure called μ4, which describes how strongly these charged amino acids interact with their surroundings and helps predict which genetic mutations might interfere with the enzyme’s function.

“One of the benefits of the machine learning method is to narrow down the set of mutations to identify the ones most likely to change the activity of OTC,” Beuning says.

Editor’s Picks

POOL learns patterns in biological data — for example, which mutations are more damaging — even when scientists don’t have complete information about every case. It predicts which variants are likely to cause stronger or weaker effects based on available evidence.

The scientists selected 17 disease-associated mutations and one additional mutation to study in detail. Half were predicted to cause disease by directly impairing the enzyme, and the other half by some other mechanism.

POOL combined with μ4 analysis was able to predict correctly which 17 out of 18 mutations hindered the enzyme’s ability to do its job. Most of the mutations that did not hinder the enzyme in a test tube did hinder the enzyme in cells.

The team also proposed possible explanations for how the disease develops after analyzing the affected enzymes in cell cultures.

“The scale at which we did this study would not have been possible without the innovations from our doctoral students,” Beuning says. “Their very dedicated effort made it possible to obtain the enzyme and study its mutations in the laboratory to determine the effects of the mutations at the molecular level.”

The findings show that the μ4 measure can complement existing bioinformatics tools for predicting how mutations affect enzyme activity.

Ondrechen says the research has already revealed some reasons why certain mutations directly impair the enzyme’s ability to speed up chemical reactions. The next challenge is to understand why other mutations, which don’t affect catalysis directly, still lead to disease.

“That’s the tougher question, and that’s what we’re pursuing now,” she says.

There are many possible explanations, Beuning says, from the amount of protein the cell makes to its interactions with other proteins in the pathway.

“We are now working on understanding these other contributing factors to the enzyme activity to determine how these different mutations affect activity, which of course could be different factors for the different mutations,” she says.