For American students in London, the cost of World War II hits home

Students studying at Northeastern University in London visited the World War II memorial site where 3,811 war dead are buried and another 5,127 missing are remembered.

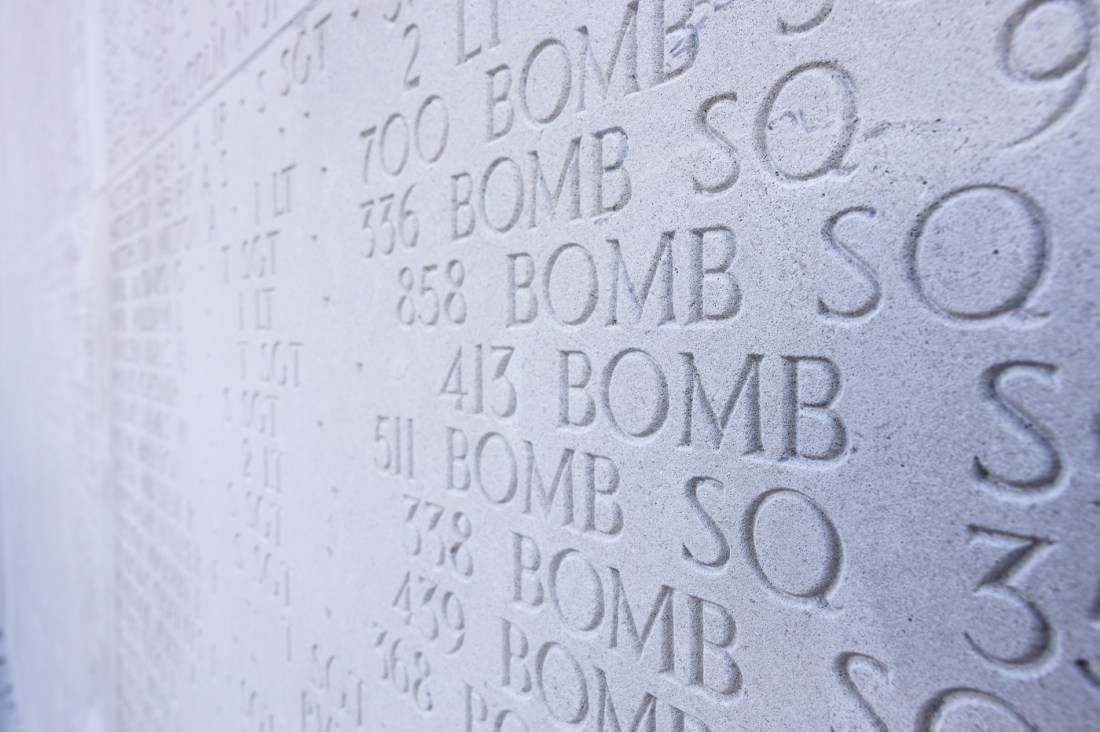

LONDON — The Wall of the Missing dwarfed Jamison Nielsen as he stared at the imposing slab of graying Portland stone.

The 500-foot-long wall in Cambridge American Cemetery bears the weight of the inscribed names of 5,126 men and one woman who served in the U.S. military during World War II and were never found.

Another 3,811 of their comrades who perished fighting for freedom on foreign soil have been laid to rest in the cemetery under its immaculately kept lawns.

Nielsen, an American architecture major studying in London with Northeastern University, said he felt a deep emotion as he stood in front of the wall, which lists the names of those missing-in-action, along with their squadron and home state.

As the midday sun stilled the cold North Sea winds that were blowing through, the 19-year-old searched the wall for mention of those from his home in Washington state. “These people might have some similar history to people from my town,” he remarked.

The freshman was part of a group of students who, on Nov. 1, ahead of Veterans Day, visited the American military memorial, situated about 5 miles outside the historic city of Cambridge, England. The trip was arranged by Northeastern history professor Olly Ayers and the university’s London student life team.

For Nielsen, the connection to these countrymen and their sacrifice is closely felt, coming from a family of servicemen. Both his grandfathers served during the Vietnam War and his father was awarded the Bronze Star by the U.S. Armed Forces for his work as a surgeon during the Afghanistan conflict.

Nielsen plans to follow in their footsteps after graduation. He is part of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program while studying at Northeastern and hopes to join the National Guard.

For him, Veterans Day is traditionally a day to rally around the community of veterans and their loved ones. “Fortunately, we haven’t had too many service members, in my family at least, who have passed away,” he said. “But we definitely know people and families that have been affected by that. This is a real day to spend with family.”

Mark Connelly, a historian and tour guide from the Connelly Contours company, told the students how there was a decision in the mid-1950s to relocate American war dead who were buried in the east of England to one permanent memorial site. The land was purchased by the United Kingdom government and given to the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Some of those memorialized are well-known, including Navy bomber pilot Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. who was killed in action in 1944. His younger brother, John F. Kennedy, would go on to become president of the United States. Others are known simply as “Unknown Soldier” after attempts to discover who they were proved impossible.

Massachusetts-based firms were brought in to design the cemetery layout. The architectural firm Perry, Shaw, Hepburn and Dean from Boston and the landscape company Olmsted Brothers from Brookline, just outside Boston, were involved in the project.

They took inspiration from U.S. memorials, including the National Mall in Washington, D.C., when putting together the layout, including incorporating a reflective stretch of water running in front of the Wall of the Missing and the memorial chapel.

The chapel interior contains a giant mural map of U.S., British and Canadian military, air and naval operations in Europe during the fight against Nazi Germany. Each U.S. state seal is represented in its windows overlooking the graves.

The headstones, topped with crosses and other religious symbols, fan out and sweep toward the rolling countryside beyond. Nielsen said it reminded him of the East Coast of the U.S., especially on a fall day like he experienced, with the oranges and reds of the English oak tree leaves in full color.

Editor’s Picks

Meher Jammalamadaka and Aarohi Agarwal, both from Texas, used their time after the tour to reflect on what the visit meant to them. As they studied the maps of the conflict and read the names of the fallen, Argarwal, 19, said it brought history to life.

The economics major had visited memorials back home but said it left a lasting impression to see a memorial in a foreign country.

“It was sad but it also gives you a sense of pride in your nation,” Agarwal said. “You understand the impact that your country had on others and it allows you to see the full extent of it.”

Jammalamadaka, a biochemistry student, described the memorial as a unique way to learn about the past.

“I wasn’t aware of how many Americans were buried overseas,” she said. “It was a very impactful experience and it helps you to understand a bit better.”

Prof. Ayers said remembrance of World War II has taken on a “different meaning” now that only a dwindling number of veterans who fought in the conflict are still alive.

“That’s why places like the Cambridge American Cemetery,” he continued, “arguably have become even more important — going there, seeing the thousands of graves and the long lists of the missing brings home viscerally the scale of the sacrifice.”

Andy McCarty, director of the Dolce Center for the Advancement of Veterans and Servicemembers at Northeastern, said the type of experience the college’s London students had in Cambridge can be “deeply impactful” in understanding the U.S.’s part in World War II, a six-year conflict that saw American troops battle in Europe, the Pacific and North Africa.

The Air Force veteran recalled the effect it had on him when visiting battle and memorial sites in France almost 10 years ago.

“I was struck by the reality that these were Americans who left home forever,” McCarty said. “Even in death they haven’t returned to the U.S. They can’t be easily visited by their loved ones, and so it’s even more important as current-day ambassadors of our nation to visit these places and pay our respects.”