The federal government wants you to adopt ‘end-to-end encryption’ methods. Here’s why you should adopt them

After revealing that it was the target of a sweeping hacking campaign, the federal government issued a public service announcement urging the public to use “end-to-end encryption” methods.

After revealing that it was the target of a sweeping hacking campaign, the federal government issued a public service announcement this week urging the public to use “end-to-end encryption” in order to better secure its digital communications.

The hack, which the FBI says was perpetrated by the Chinese government, compromised the FBI, AT&T and Verizon primarily, but also both 2024 presidential campaigns and other high-profile targets, including prominent politicians.

U.S. officials describe the hack, dubbed Salt Typhoon, as one of the largest of its technology infrastructure in the nation’s history.

So, what is end-to-end encryption, and how can consumers and technology users protect themselves in the wake of this massive breach?

Most people today engage in some form of digital communication, whether that’s iMessage, Google Messages, WhatsApp or SMS. Some of those methods of communication already use end-to-end encryption (iMessage and WhatsApp), while others do not.

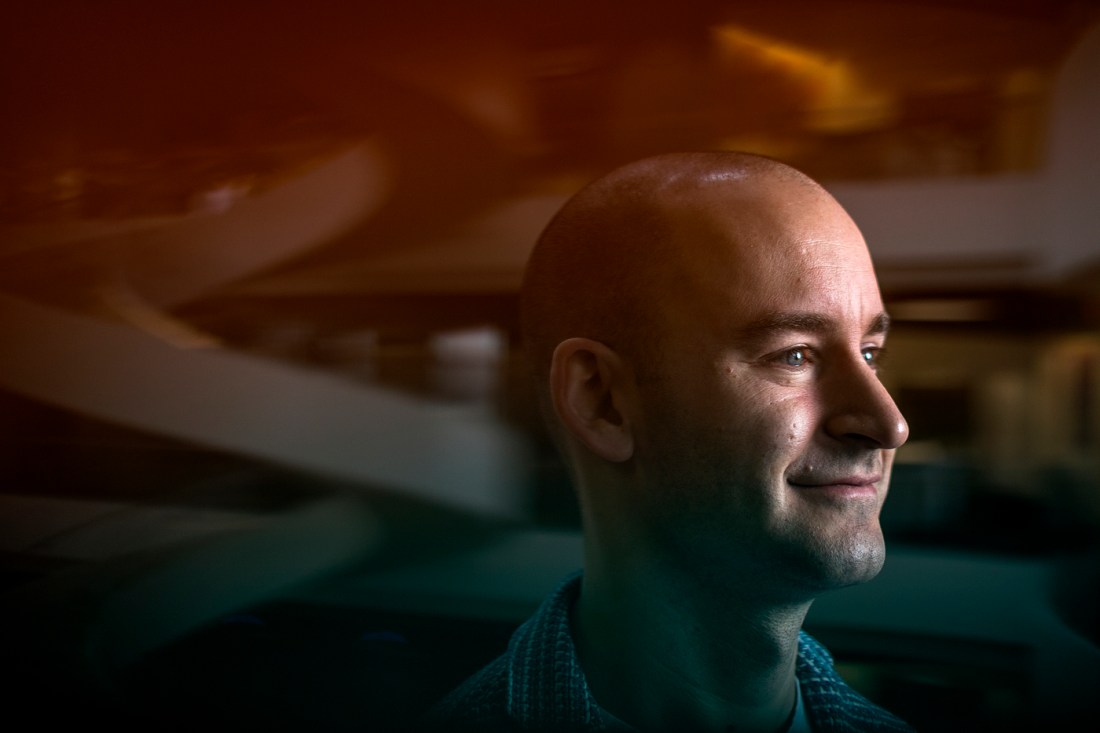

Quite simply, end-to-end encryption means that only the end users in a digital communication can “decrypt” — that is, read and understand — the contents of a message or communication, says Christo Wilson, a professor of computer science at Northeastern University. It is facilitated by some form of technology, usually an app that can be downloaded onto a device.

Message-based apps such as WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram are designed around end-to-end encryption. But most of our day-to-day communications are not end-to-end encrypted because they are handled by third parties, Wilson says.

When a cellphone user decides to send a text message to another user, the contents are packaged in a digital code that is then sent, via some network, to the other person. The same applies for the sending and receiving of messages on a social media platform such as Facebook, Instagram and X (formerly known as Twitter). Communications on those platforms move through servers that are overseen by individuals with access to them.

“The crucial distinction here is that, for any messaging system, it doesn’t just involve you and me, or the endpoints. There are also the middlemen, the intermediaries,” Wilson says.

Those intermediaries have access to the communications by virtue of the fact that they provide the service. For Short Message Service, or SMS, a text message service, the intermediary is the phone company. For Facebook Messenger, it’s Meta. Google is the intermediary overseeing communications over Gmail and Google Chat.

Can employees of Verizon, AT&T and Meta read the messages sent between users? Wilson says SMS has no encryption whatsoever, so the phone company can see everything sent and received by users. “In fact, anyone who is watching the traffic can see everything,” he says.

Editor’s Picks

With a service such as Facebook Messenger, messages are encrypted only while in transit to the other user — that is, as they are en route to Facebook, which then sends the message to the other user (it is encrypted while in transit to the other user as well), Wilson says.

“End-to-end encryption is only you and me, which means the intermediaries can’t read the messages at all,” Wilson says.

As cyberthreats grow more sophisticated and omnipresent, Wilson says that tech users should adopt end-to-end encryption. That requires moving communications over to an app like WhatsApp or Signal, which Wilson says are “very user-friendly.”

“In my opinion, it should be the default,” he says.

The federal government’s explicit endorsement of the protective technology represents a significant shift, as FBI officials over the last decade have repeatedly demonized end-to-end encryption methods as impeding investigations. (In 2014, then FBI Director James Comey said that encryption technology interferes with the government’s ability to prosecute crimes and prevent terrorism.)

“The FBI, in particular, has been very vocal against end-to-end encrypted apps in the past because they said they need wiretapping capabilities,” Wilson says. “Now that those capabilities are being abused, they seem to be coming around and taking the opposite approach.”

While he agrees with the federal government’s latest guidance, the irony of the situation is not lost on Wilson — and others in the cybersecurity field.

“The FBI and the federal government more broadly have been asking for back doors in technology for a long time for wiretapping,” Wilson says. “That is exactly the mechanism being used by this threat actor, Salt Typhoon, to break into the telecom networks.”