How the dominance of big companies like Nvidia is creating a ‘split world’ in tech

Nvidia’s stock is up roughly 200% in the last year and has helped push the technology-heavy S&P 500 to record highs, accounting for more than a third of the index’s gains this year.

Yet, only three companies — Microsoft, Nvidia and Apple — account for over 20 percent of the value of the S&P 500.

Northeastern University’s Vincent Muscolino says the dominance of big companies like Nvidia is creating a “split world” in tech, and upending the traditional tech company model of success.

“What’s pretty remarkable to me is how outsized the large companies are getting,” says Muscolino, a senior lecturer in finance and a technology market expert at Northeastern. “I think there’s worry about this split world between trillion-caps (companies with multi-trillion dollar market values) and the rest of tech.”

For years, successful tech companies have followed a familiar playbook — develop a disruptive product or idea, get funding, get market share and dominate.

IBM achieved this with its mainframe computer and then, along with Apple, with personal computers. Amazon, eBay and other companies benefited — and many companies went bust — during the internet boom and bubble of the 1990s. Facebook and social media companies dominated the 2000s and 2010s, and now “here we are with AI,” Muscolino says.

Featured Posts

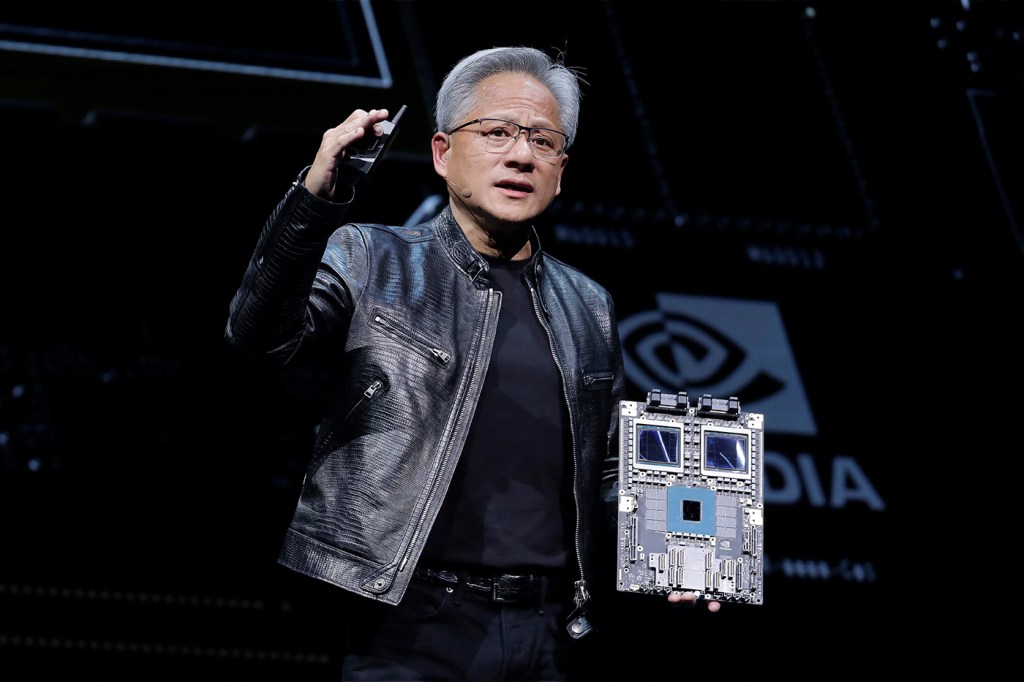

And after decades as “much more of a non-exciting story,” according to Muscolino, Nvidia is now a dominant AI leader — banking on the power of its products to enable AI and machine learning.

But if a new trillion-cap company is introducing a new area of tech investment (doesn’t it seem like all large companies are investing in AI, nowadays?), what’s with tech layoffs?

The tech industry is polarized, Muscolino explains.

On one end is big tech. Small startups that are snatched up by big tech before they have the chance to grow and create competition represent the other extreme.

“You get into the trillions of valuation, you can buy whatever you want and you have the resources to sustain market advantage,” Muscolino says.

“It’s hard for young firms to get to be the next new thing if they keep getting bought up,” Muscolino continues. “You can still do a startup, but it’s getting harder to raise capital”

That can be problematic for encouraging creativity in the tech sector in general. Startups are a necessary lifeline to foster new thinking and new products, Muscolino says.

“If big tech companies are reducing headcount, people have to find jobs in higher-risk startups,” Muscolino says. “It’s a lot easier to be creative when you’re hanging your own shingle.”

But the consolidation also creates lots of money.

“I’m looking at Apple and Microsoft and they have great profit margins, so it can be a good thing mega-tech balance sheets,” Muscolino says.

Add Nvidia to that list.