Northeastern student and Gideon Klein Scholar kicks off Holocaust and Genocide Awareness Week with ‘solo biographical performance’

On Monday, the Cabral Center at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute became a makeshift exhibit that helped to tell the story of Northeastern student Andie Weiner’s grandfather.

“Everything you will hear today is true — the events and the stories.”

That’s how Andie Weiner, the 2024 Holocaust Legacy Foundation Gideon Klein Scholar, prefaced her presentation at the kick off of Holocaust and Genocide Awareness Week at Northeastern University.

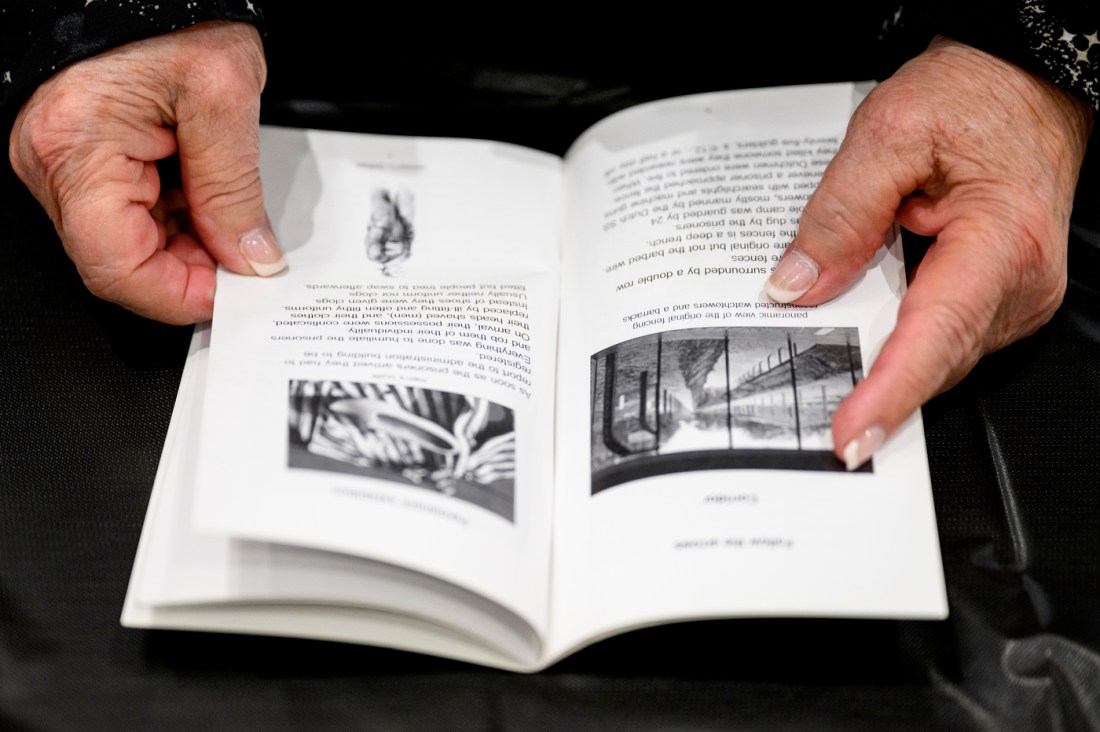

The presentation, also her capstone project, was a “solo biographical performance” that told the story of how her grandfather, Jack or “Joop” Groothuis, escaped the Netherlands as it was under Nazi occupation and fled to the United States.

A fourth-year theater and psychology major at Northeastern, Weiner chronicled how her great-grandmother, Helen Copenhagen Groothuis, hid her grandfather — then an infant — with a local Christian family following the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands in 1940.

In 1946, Jack was reunited with his mother and they moved to New York to live with her sister, Marjana (Marian) Schechter, Weiner said.

The Cabral Center at the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute, where Weiner presented on Monday, became a makeshift exhibit displaying historical photographs and artifacts from the time period.

“I’ve always been interested in survivor stories as the primary mode of storytelling and education about the Holocaust,” Weiner told the audience. “Throughout my life, I’ve been doing research and learning about this, and this opportunity was presented to me as a way to really connect the family history.”

Weiner detailed her grandfather’s story in a Northeastern Global News article in advance of Holocaust Remembrance Day in January.

Featured Posts

Helen hid Jack in Vught, a town 59 miles southeast of Amsterdam. There, he spent the first two years of his life being raised by Jo and Lanie van de Meerendonk, hidden in plain sight from the Nazis who ran the Herzogenbusch concentration camp out of the town.

Asked about what she makes of the recent wave of antisemitism, she underscored the “dangers of staying complacent,” pointing to the power of storytelling to conquer hate.

“To truly know what people have experienced, to have these verbatim letters — nobody can deny these experiences,” she said.

“Throughout my life, I’ve been doing research and learning about this, and this opportunity was presented to me as a way to really connect the family history.”

Weiner said she originally planned to write the story as a series of monologues or a play. But rather than attempt to fictionalize the lives of those involved, she decided she wanted to hew as closely to the truth as possible.

“It wasn’t until I was probably 10 that I truly understood what happened,” she said. “That was also around the time I started learning about the Holocaust in school. I was very fortunate to grow up in an area with a lot of Jewish people, and a lot of those Jewish people had parents or grandparents who were survivors.”

The Holocaust Legacy Foundation Gideon Klein Award helped fund a recent trip that allowed Weiner to conduct more research into her family tree. The $5,000 award — named for Gideon Klein, a pianist and composer who was imprisoned in multiple concentration camps until his death in 1945 — is given to a student creating an original work, performance or research related to the art of the Holocaust.

“We have a very long tradition of Holocaust memorialization and education programming at this university that dates back to 1972,” said Simon Rabinovitch, Stotsky Associate Professor of Jewish Historical and Cultural Studies at Northeastern.

Lori Lefkovitz, Ruderman Professor of Jewish Studies and director of Northeastern’s Jewish Studies Program, praised Weiner for her “creativity and innovation.”

“It has been remarkable year after and year, and often I am surprised that students come up with yet another strategy for teaching about the Holocaust and learning about things we didn’t know before,” Lefkovitz said.