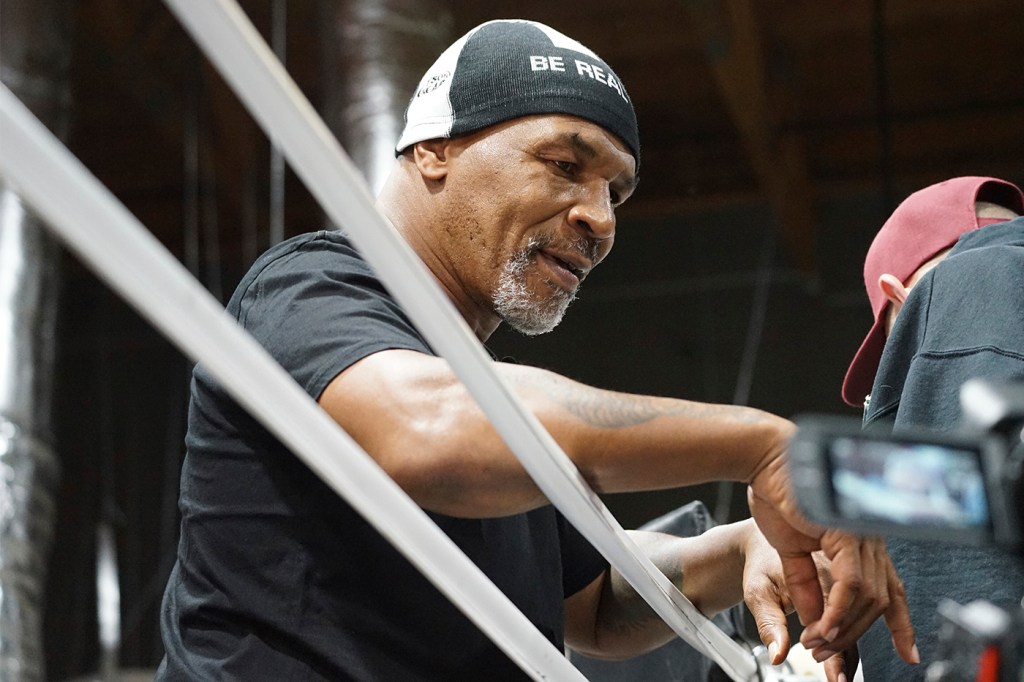

Mike Tyson is returning to boxing. But at 58, experts say it’s a bad idea.

A neuroscientist and a doctor agree: Tyson is at far greater risk of traumatic brain injury at his age, should he decide to step back into the ring.

Mike Tyson is scheduled to return to the ring this summer in a bout with social media star turned professional boxer Jake Paul. The exact details of the fight have yet to be worked out, but the event will be streamed on Netflix on July 20.

But there’s a problem. Tyson, considered one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time, will be 58 years old on the night of the fight. A brain health expert and a doctor agree: it’s not a good idea for Tyson to be risking his health at that age against a far younger opponent (Paul is 27).

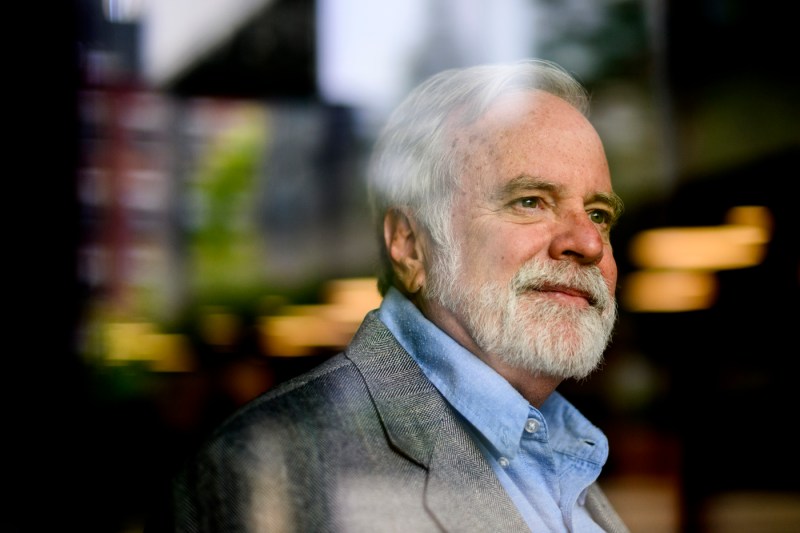

That’s due to a number of factors, chiefly the cumulative and lifelong effects that earlier traumatic brain injuries have later in life, says Art Kramer, professor of psychology and founding director of the Center for Cognitive and Brain Health at Northeastern University.

“We’re fortunate that there have been fantastic medical advances to help us do all sorts of things at advanced ages, but that doesn’t mean that aging doesn’t interact with head trauma, and the few studies that have been done suggest that it gets more serious as we get older,” Kramer says.

Structurally, the brain shrinks in size as a person ages, meaning there is more room for it to move around in the cranium. The blood vessels in and around the brain also shrink with age, becoming more brittle and susceptible to damage.

Those changes would put Tyson at increased risk for subdural hematoma and intracranial hemorrhage, says Gian Corrado, head team physician for Northeastern athletics and director of emergency sports medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“He has a couple strikes against him,” Corrado says. “One is his age. There is clear data that says the risk of brain injury goes up after 50. And then you have the fact that he has almost definitely suffered brain injury from previous fights.”

To be clear: pugilists of all ages put their health on the line when they take to the ring, and there are examples of boxers competing in sanctioned events around the age Tyson is now. But the risks facing older fighters are more pronounced.

“There are a number of reasons why it’s more dangerous,” Kramer continues. “One is that the head trauma you have when you are younger tends to hang around, even subtly, sometimes for many, many years. But as we get older, we also have many other separate issues that have to do with brain function, brain structure, cognition and so forth.”

The American Academy of Neurology classifies boxing as a sport that “includes intentional trauma to the brain,” and has enumerated recommendations intended to reduce harm to participants.

The group says that children are increasingly becoming involved in sports that pose risks to brain health.

“And we know that repeated head injuries aren’t good for anybody, regardless of what age,” Kramer says.

Kramer has co-authored several studies on the effects of traumatic brain injuries on cognition and brain health. Though he notes that there is still a lack of longitudinal data on the subject, the most sinister outcome from repeated blows to the head over time is a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which can lead to dementia.

“What we know is that, even many years later, these concussions, or what people call mild traumatic brain injuries, tend to have long-lasting effects,” Kramer says.

Kramer — a former boxer himself — says that most professional boxers sustain concussions at one point or another.

“There are different levels of traumatic brain injury, starting with mild, and then it can go to severe where you’re knocked out for some number of minutes,” Kramer says. “And most boxers have gone through both — and many people have gone through both.”

Another risk factor for Tyson might be any medications he is taking.

“Even something as simple as an 80 milligram baby aspirin, which will help your blood thin out a bit — taking those blood thinners and then getting into the ring could cause more bleeding in the brain,” Kramer says.

In a sport where knocking your opponent unconscious is arguably the goal, Corrado notes, also, that reflexes slow with age — another vulnerability that would put Tyson at a deficit.

“There’s plenty of data that he won’t be able to protect himself like he may have been able to when he was 30,” Corrado says.

Tyson’s last professional boxing match was in 2005, when he lost to Kevin McBride. He participated in an exhibition against Roy Jones Jr. in 2020.