Her grandfather survived the Holocaust thanks to the bravery of one Dutch family. Eighty years later, she’s uncovering the story

Andie Weiner, a fourth-year theater/psychology student, traveled to the Netherlands for research for her theater capstone project about how a Christian family hid her grandfather as an infant during the Holocaust.

Jack Groothuis’ life was at risk from the moment he was born to two Jewish parents during the Holocaust.

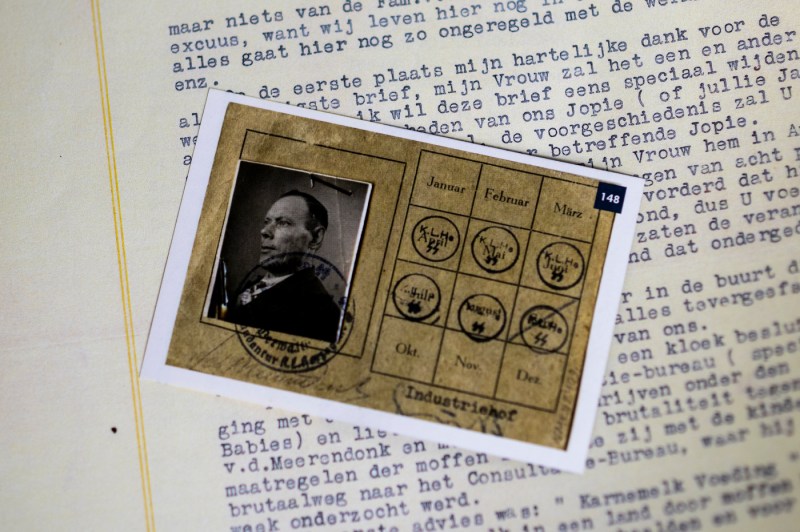

To protect her son, his mother, Helen, placed him into hiding with a Christian family in Vught, a town about 59 miles southeast of Amsterdam. Jack spent the first two years of his life being raised as a member of the family by Jo and Lanie van de Meerendonk, hidden in plain sight from the Nazis who ran the Herzogenbusch concentration camp out of the town.

Once the country was liberated from the Nazi regime, mother and son reunited and came to America. For many years, no one in either family spoke much of this story, a common response in Holocaust survivors. But now, 80 years later, Jack’s granddaughter, Andie Weiner, a fourth-year Theatre and Psychology student is telling the story of how one family risked everything to help another.

As part of her theatre capstone, Weiner is creating an interactive installation dedicated to educating people on this story and the horrors of the Holocaust. The installation is centered around the town where her grandfather was hidden and the stories of three different types of women during the Holocaust: Jewish women, women in the resistance who hid Jewish children, and anti-Semitic women.

“When most people think about the Netherlands in relation to the Holocaust, they think of ‘The Diary of Anne Frank,’ which is a wonderful story,” Weiner said. “But there is so much more … this is a story about the 1940s and the Netherlands. This is a story about Jewish people persevering through the worst and how one story had a somewhat happy ending. But I also want to highlight that most stories did not have that ending. But I want people, regardless of what they think, to just know this happened because so many people deny it. So many people are not holding space for the Holocaust right now and I think people need to hold space for it as part of history.”

While the project is part of Weiner’s capstone, a recent research trip she took for it was made possible by the Holocaust Legacy Foundation Gideon Klein Award. The $5,000 award — named for Gideon Klein, a pianist and composer who was imprisoned in multiple concentration camps until his death in 1945 — goes toward a student creating an original work, performance or research related to the art of the Holocaust.

Weiner was named the Gideon Klein Scholar for the 2023-2024 school year. With the funds, she and her mother embarked on a trip to the Netherlands over the holiday break in order to learn more about their family story. The pair spent two and a half days in Amsterdam and then two days in Vught where Groothuis was hidden. They stayed with the grandson of the couple who hid him and visited Herzogenbusch, which is now a memorial and houses an educational museum.

Editor’s Picks

The visit helped Weiner get a sense of the town and its role in the Holocaust. In addition to housing the only concentration camp west of Germany, the town was also home to Harry Holla, a resistance leader who connected Jewish families with those who might conceal their children. Weiner not only got to see the museum and camp memorial, but also the building where her grandfather was hidden and the house in a coastal town where they think her great-grandparents hid prior to her grandfather being born. They also traveled around and met up with some distant relatives.

The mother and daughter went into the trip with some background information. Jack Groothuis remained close to the van de Meerendonk family, including Sis and Ad, the son and daughter-in-law of the couple that took him in who helped raise him. After the daughter-in-law passed away last year, Weiner said her mother and the remaining relatives resolved to look into their shared past.

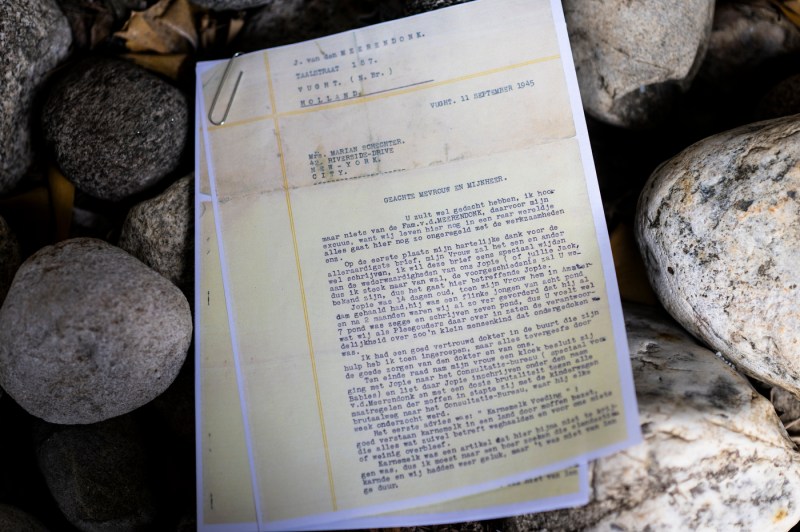

In October, the families found letters sent between the two families, including letters Helen Groothuis wrote to her sister and son in case of her death. They also found letters from the van de Meerendonks to Groothuis’ aunt, outlining the child’s life with them, including the time a Nazi soldier bunked with the family when fleeing the camp post-liberation and held Jack, not knowing he was a Jewish child in hiding.

But the trip didn’t fill in all the blanks. It’s still not clear how Weiner’s great-grandparents connected with the van de Meerendonks or why the latter were willing to put their lives on the line to protect this child. The circumstances leading up to the handoff are also unclear: Weiner said they suspect someone told on her great-grandparents while in hiding and the couple got separated. The family believes Weiner’s great-grandfather may have been imprisoned in Auschwitz when he died in 1945.

“What we’ve learned was after the war, nobody talked about it. They all just moved on with their lives, mostly because of the trauma,” Weiner said. “But there’s so much we don’t know. Nobody wanted to talk about it. That’s what I really learned on this trip. … It kind of changed for me how I wanted to tell this story for the festival. Education is the most important thing when it comes to the Holocaust. Most people who truly remember it are dying or dead and there are so many holes even in this story. There are millions of stories that are untold because nobody spoke.”

While Weiner, her family and the van de Meerendonks are still looking for answers (the two families have remained close throughout the years and are working to uncover more of their intertwined story), Weiner hopes this project will do the crucial work of educating people on the horrors of the Holocaust and the people who made a difference.

Visitors to the exhibit will hear these fictionalized accounts, written and recorded by Weiner, paired with photos of Vught and Herzongenbusch. Weiner will act as the guide throughout the installation as well as read the letter her great-grandmother wrote her grandfather, outlining her hopes for him in case she was killed before they could reunite.

In addition to the installation, Weiner is writing a capstone paper exploring just why this is an important story to explore and educate people on, particularly considering the rise in anti-semitism.

“What’s most heartbreaking is that yes, I grew up with a survivor and he knew other survivors and it was something we always talked about,” she said. “But most people did not have that and don’t know many survivor stories.”

The interactive installation will go up the weekend of March 14-16 for the Theatre Department’s Capstone Festival, as well as the week of March 25th as during Holocaust and Genocide Awareness Week. But for Weiner, it is only the beginning of this story she plans to spend her life telling.

“There is so much that is just completely gone,” she said. “That was really, really hard for everyone to grapple with in both my family and the van de Meerendonk family. It was right after (the van de Meerendonk’s sister-in-law died) where my mom and Ad’s oldest son were like we need to work together (on uncovering this). … I know this is going to be a lifelong project. It’s something I’m very proud of. We’re living in a time where anti-Semitisim is a lot and I want to keep telling stories about persevering.”

Performances of Weiner’s Capstone will be held on Thursday, March 14 and Saturday, March 16. For more information, visit the Theatre Department’s Capstone Festival page.

Weiner will also perform her capstone in the Cabral Center on March 25 at 6 p.m. for Holocaust and Genocide Awareness Week.