Are fairy tales fair? AI helps find gender bias in children’s storybooks

Snow White, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty have more in common than their origins as classic fairy tale figures and, now, part of Disney’s famous roster of characters. Their fairy tales are also full of gender bias and stereotypes, according to literature scholars––and now AI.

A team of researchers from Northeastern University, University of California Los Angeles and IBM Research have created an artificial intelligence framework that can analyze children’s storybooks and detect cases of gender bias.

The way fairy tales depict and teach lessons, morals and sociocultural roles to children, particularly young girls, has been discussed in academia and beyond for decades. These stories are full of princesses who need saving and handsome princes who are there to save them.

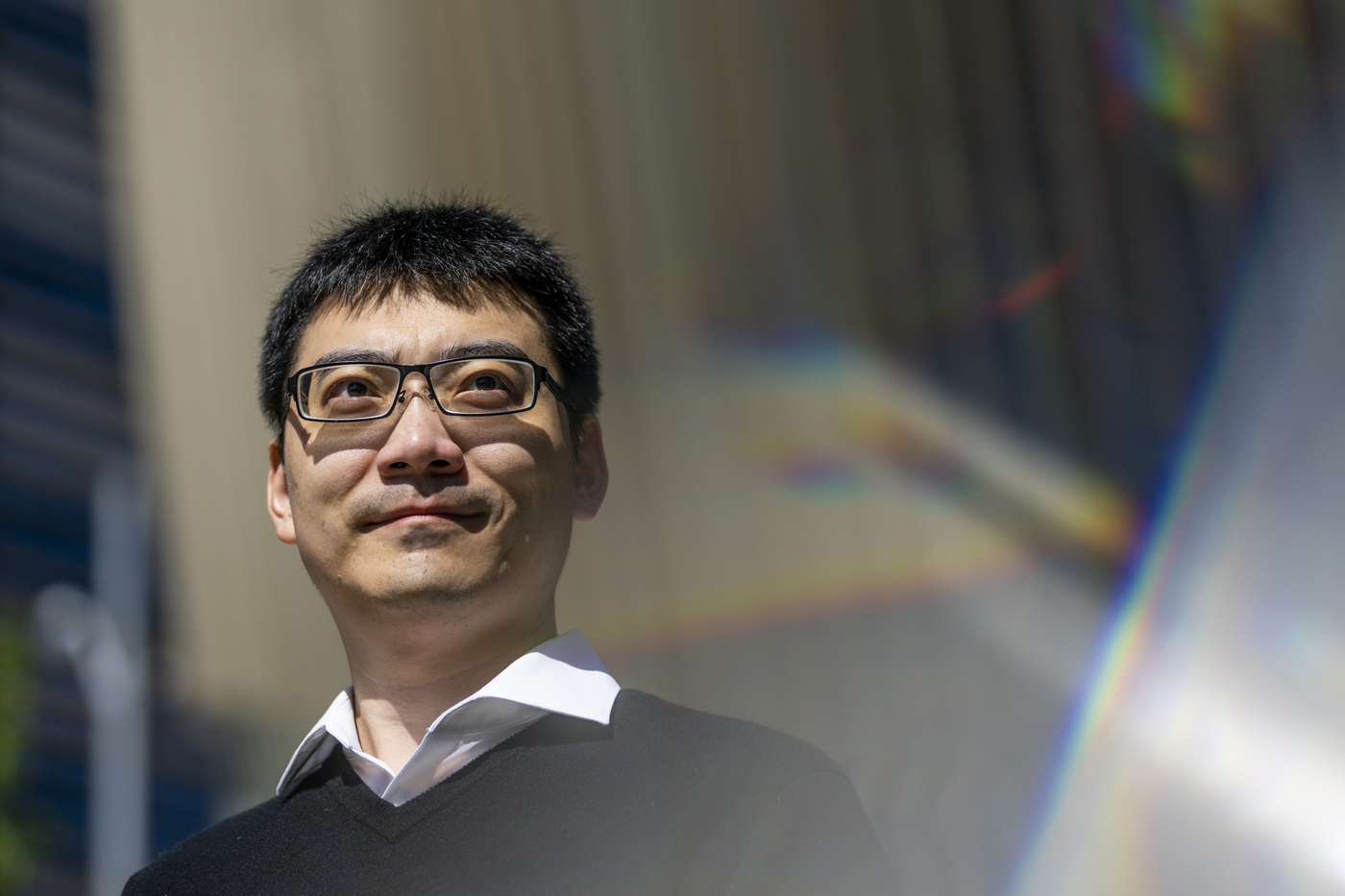

The hope is that the AI-driven, spellcheck-like tool his team has created will be used by writers and publishers, as well as researchers, to create more inclusive stories for children, says Dakuo Wang, an associate professor at Northeastern and one of the researchers on the project.

“If in the future I have a baby girl, I don’t want her to feel discouraged to take on those tasks or conquer those challenges [or] say, ‘Someone will come save me’ or ‘It’s not supposed to be something I would do as a girl,’” Wang says. “If we can develop a technology to automatically detect or flag those kinds of gender biases and stereotypes, then it can at least serve as a guardrail or safety net not just for ancient fairy tales but the new stories being written and created every day today.”

All of this work started as part of the team’s ongoing research into how AI can help build language learning skills for young children. The team was already interested in fairy tales as tools for language learning and had collected hundreds of stories from around the world to use as the “corpus” for their algorithm to analyze.

They recruited a group of educational experts––teachers and scholars––to comb through the stories and create a list of questions and answers that would help prove whether a child was learning from these stories. The end result was 10,000 question-answer pairs––and the realization that all of these stories, no matter where they came from, had “stubborn and profound” gender stereotypes in them.

The princess eats a poison apple, gets imprisoned, kidnapped or cursed or dies and has no agency to change her situation. Meanwhile male characters––princes, kings and heroes––were killing dragons, breaking the curses and saving the princess.

Previous research in this area focused on what Wang calls the “superficial level” of bias. That meant analyzing stories and identifying word or phrase pairings, like “prince” and “brave,” that connect ideas and identities in specific ways. But Wang and the rest of the team wanted to go deeper.

They focused on “temporal narrative event chains,” the specific combination, and order, of events and actions a character experiences or takes.

“It’s actually the experience and the action that defines who this person is, and those actions influence our readers about what [they] should do or shouldn’t do to mimic that fictional character,” Wang says.

Using the hundreds of stories they had collected, the team created automated processes to extract character names and genders along with every event. They then aligned those events as a chain for each character. They also automated a process to group events and actions by specific categories. Each event was analyzed and given an odds ratio, how frequently it was connected to a male or female character.

Of the 33,577 events analyzed in the study, 69% were attributed to male characters and 31% to female characters. The events associated with female characters were often connected to domestic tasks like grooming, cleaning, cooking and sewing, while those for male characters were connected to failure, success or aggression.

With all that information, Wang and the team created a natural language processing tool that could go beyond analyzing individual events to find bias in event chains.

“Someone is being saved and then getting married and then living happily ever after; some others killed the monster, saved the princess and lived happily ever after,” Wang says. “It’s not the ‘lived happily ever after’ part or ‘get married’ part that are different. It’s actually the events happening before these events in a chain that make a difference.”

By automating this process, Wang says he hopes the tool will find use among people outside the research community who are actually creating––or recreating––these stories. In the process, they can start preventing stories from passing down these outdated, harmful ideas to the next generation.

“With our tool, they can simply upload their first draft into a tool like this and it should generate some score or meter that indicates, ‘Here are the things you may or may not want to check. If this intention is not what you would want to express, then maybe you should think about a rewrite. Here are some suggestions,’” Wang says.

Moving forward, Wang and the team plan on expanding their work to look at other forms of bias. They will also be using their tool to evaluate the biases of other AI. They hope to use their algorithm to analyze whether ChatGPT has the same gender biases and stereotypes when it creates content based on these stories.

“We are proposing that this is actually a task, a task that the technical community can actually help to conquer,” Wang says. “We’re not saying our method is the best. We’re just saying our method is the first to do this task, and this task is so predominant. … Maybe we should shift some of our attention to these existing social challenges and tasks.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.