How to rebound from disasters? Resilience starts in the neighborhood

The Beatles might have gotten it right.

When disaster strikes, you truly do get by with a little help from your friends, according to a new report co-authored by Ann Lesperance, director of the College of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Northeastern University Seattle campus.

“Many times in emergency management we think about the physical activities that need to be done, expanding this, building that, shoring up this. But there’s a whole other side that we could easily do that can also enhance the recovery process,” says Lesperance, who is also director of the Northwest Regional Technology Center for Homeland Security at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Left to right: Ann Lesperance, director of the College of Social Sciences and Humanities at the Northeastern University Seattle campus; Daniel P. Aldrich, professor of political science, public policy and urban affairs, and director of the Security and Resilience Studies Program at Northeastern. Photo by Andrea Starr/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

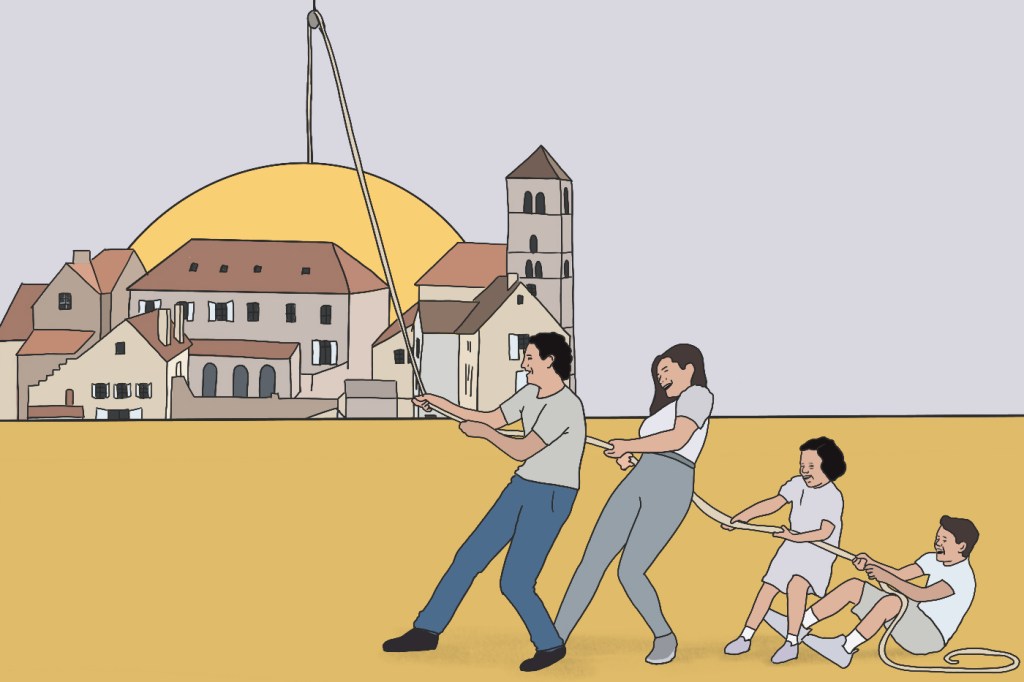

There’s a growing consensus among emergency response researchers that in communities where social ties are strong and there is a sense of connectedness, residents are more readily able to rebound after a disruptive event such as an earthquake, hurricane, tornado, wildfire, or illness. So the Federal Emergency Management Agency asked a committee of experts in hazard mitigation, community resilience, engineering and disaster recovery (including Lesperance) to distill that body of research in order to inform emergency managers how they might build resilience within a community. The resulting report was published in May by The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

“Researchers have found that bringing people together, creating that sense of community and identity—no matter what it is—will enhance response and recovery,” Lesperance says.

The idea is that when trouble comes, the most resilient communities are the ones in which individuals and families have others they can rely on for help, established relationships with emergency responders or authorities, or simply plans for collectively responding to a disaster. Neighborhoods might have a phone tree set up so residents can check on each other to make sure everyone is safe, for example.

That’s what Lesperance’s own community has set up. “Here in Seattle, we’re waiting for the earthquake,” she says. So in Lesperance’s neighborhood, the residents have assembled an inventory of who has a chainsaw, water purifiers, food stores, and other emergency equipment. They’ve come up with a meeting spot and a list of residents that details who has kids and pets.

“I don’t know all the details about who has a chainsaw,” she says. “But I know we [have one]. And I know that when the earthquake happens and we show up at that meeting spot, someone will say, ‘yeah, I’ve got one.’ It’s neighbor helping neighbor, families helping families that will help get us through any type of a disaster.”

The local fire department organized this planning, hosting meetings among the neighbors and advising them, Lesperance says. But it was the neighbors themselves that asked the firefighters to help them set up a system.

These concepts may seem familiar, particularly in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, says Daniel Aldrich, professor of political science, public policy and urban affairs, and director of the Security and Resilience Studies Program at Northeastern. Aldrich’s research on resilience is cited in the committee’s report. He has also been studying the role of social ties in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We need our friends. At the end of the day, needing connection, needing this kind of social capital to get through a shock, I think that’s pretty clear to most of us, going through COVID-19,” he says. In fact, Aldrich says, we never should have used the term “social distancing” when we meant physical distancing from others.

There are three categories of social ties that Aldrich has found are important to creating resilience in a community. First, there are “bonding ties,” which connect people who are similar, sharing traits or backgrounds. “Bridging ties” connect people who are different from one another, and have different backgrounds but shared experiences or places. Those social ties form through religious organizations, schools, clubs, or sporting events. The last category Aldrich calls “linking ties.” These types of relationships connect regular people with people in leadership positions, and build trust in formal emergency-response organizations.

“We need all three types of those ties during a shock,” Aldrich says. “Without them, things go really badly.” And in his research, he found empirical evidence of that occurring early in the pandemic.

“As COVID-19 was first developing, we showed, across communities, where there was vertical trust, where I listened to people above me, and took on those kind of measures to protect myself—wearing a mask, keeping six feet apart, not going into work—there were fewer cases to start with,” Aldrich says.

“Then, as cases penetrated across society, across different levels of connections,” he says, “where people have stronger bonding ties and bridging ties, there are fewer deaths. People are taking care of each other. They’re going to get their neighbors to an ICU. They are knocking on doors and delivering food or toilet paper. They’re dropping off masks for people who need them.”

These trends are not specific to COVID-19, however. Lesperance’s report is focused more on natural disasters, and Aldrich’s research originated in hurricanes, earthquakes, wildfires, and other such natural hazards.

Aldrich has found that in a major shock, such as a tsunami or hurricane, a tightly connected community will save roughly 20 times more lives than the least connected community where nobody knows anybody. A community that has trusted ties to decision-makers can also receive about 20 to 30 percent more money for building back after a disaster than communities that do not have those connections.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.