How did the Black Lives Matter movement get to where it is today?

The Black Lives Matter movement has been developing in a variety of forms for centuries, and a deep vein of its history can be explored within the Archives and Special Collections at the Northeastern Library.

More than 64,000 records are available online, including the Lower Roxbury Black History Project, which provides oral histories of a community that has been pursuing racial equity for generations. The digitization of these resources has made them accessible during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Placing the current moment in a much longer time horizon really gives you critical context,” says Dan Cohen, a professor of history who serves as vice provost for information collaboration and dean of the university library.

The Northeastern archives renew stories that have been forgotten to history—including many that resonate today.

In 1970, Frank Lynch, a 24-year-old singer, was a patient at Boston City Hospital when he and another man in his room, Edward Crowley, were shot and killed by a white police officer. In spite of protests in Boston and an investigation by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the officer did not face charges.

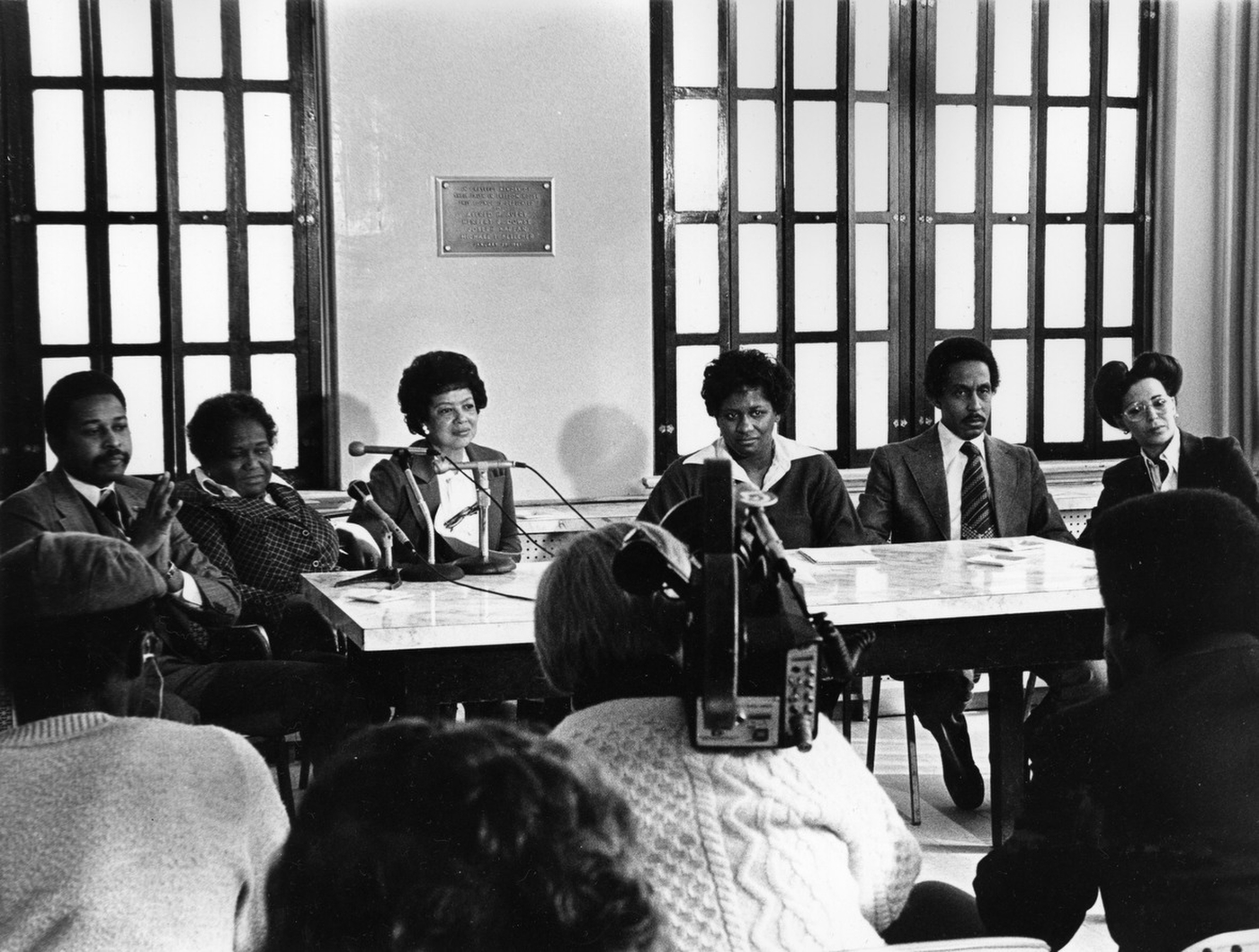

The Lower Roxbury Black History Project blends compelling narratives with everyday efforts that were made by many people to bring justice to American society on the local level.

“You see how activism is done—the meetings of nonprofit community groups, the pamphlets, the internal conversations, the letters that they wrote to other civic institutions in the city,” Cohen says. “This kind of history shows that community efforts, and individual people brought together in a collaborative spirit, have made changes to American society.”

A secret to building upon the current momentum of Black Lives Matter can be found in these records, says Molly Brown, a reference and outreach archivist at Northeastern.

“It starts with meetings,” Brown says. “It continues with conversations. And it asks us to look at all of the institutions that we participate in.”

The Lower Roxbury Black History Project was funded in 2006 by Joseph E. Aoun, president of Northeastern, based on a suggestion by Reverend Michael E. Haynes, a local leader who died in 2019. Haynes’s interview is a featured treasure among the archives.

“Today we can’t talk to Rev. Haynes in person, but we can go to his interview and keep learning from his wisdom,” says Giordana Mecagni, who heads the archives and special collections at Northeastern. “He was involved in almost every Black activist cause in Boston for many years.”

Dan Cohen, a professor of history who serves as vice provost for information collaboration and dean of the university library. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

The project includes references to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who led the 1965 civil rights march to the Boston Common from the William E. Carter Playground a decade after he had attended Boston University. His presence in the archives gives power to the actions that have been taken by people who weren’t so well known.

“People think about the civil rights movement as being exemplified by Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and Rosa Parks,” says Mecagni, who also notes renowned Boston-based activists like Melnea Cass, Muriel Snowden, and Ruth Batson. “But it was also millions of individual people with jobs and families doing their part to make sure that there was change happening. We want the people out in the streets right now to understand that there were people like them in Boston whose efforts sparked real change.”

Another trove of perspective can be discovered at the Beyond Busing: Boston Public School Desegregation project, which provides thousands of digitized resources on desegregation, starting with Brown v. Board of Education, the unanimous 1954 Supreme Court ruling that found the segregation of public schools in Topeka, Kansas, to be unconstitutional.

In 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. issued a U.S. District Court ruling in Massachusetts that called for busing to desegregate Boston’s public schools, which set off a series of protests and riots.

Left, Giordana Mecagni, head of Special Collections and university archivist, and Molly Brown, reference and outreach archivist. Photos by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University and Photo courtesy Molly Brown

“What was missing from this public narrative was the 40 years of Black activism in Boston that predated the Garrity decision,” Mecagni says. “There was a reason why the court had to intervene. It was because for years Black activists were saying, ‘Schools are not equal. This is not fair.’ And finally, Boston was forced to do something about it. But this didn’t happen in a vacuum. It took a lot of mostly unpaid volunteer work.”

“Boston’s civil rights movement is mostly remembered as being education-focused. But Boston’s activists weren’t just looking at Boston schools,” Brown says. “They are protesting racial imbalance. They’re looking at housing. They’re looking at the ways that our political constructions affect and enact white supremacy.”

The Archives and Special Collections staff is also building the archives of Northeastern’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, which was founded by Margaret Burnham, a lifelong civil rights activist and university distinguished professor of law at Northeastern. The justice project’s staff of Northeastern students investigates acts of racially motivated crimes that took place in the Jim Crow South from 1930 to 1970.

Giordana Mecagni, Head of Special Collections and University Archivist, looks through NortheasternÕs archive at Snell Library. Photo by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

“What happened to George Floyd tragically happened to thousands of other African Americans,” Cohen says of Burnham’s efforts to tell those stories. “And so this goes back a long way and that makes it even more infuriating that it’s still going on in 2020. But it also shows the broader historical context of some of the economic, social, and cultural problems that have persisted in American society.”

Additionally, the library’s Teaching with Archives Program offers an array of opportunities for experiential learning with archival records, such as documents, photographs, local newspapers, and architectural plans related to the history of Boston’s social justice organizing as well as Northeastern’s history. The program encourages reflection about the participants’ own role in history, and how their neighborhood, school, and beyond are part of the story of Boston’s past and present. Teachers may access a variety of digitized community collections, including:

Northeastern’s archivists have used the Boston Public School Desegregation collection to teach hundreds of Boston Public School students about the education history of their city.

The library’s archives are an important resource for understanding racial injustice during this polarized time, says Cohen. Northeastern’s library is home to the Boston Research Center, a digital community history and archive lab that aims to bring Boston’s deep neighborhood and community histories to light through the creation and use of new technologies.

“The key service that we provide is knitting all of this together,” Cohen says. “Obviously, there are people who are interested in history. There are researchers who work with maps and data. There are social justice activists; there are community historical societies.

“The library is the institution that can synthesize the wide variety of materials that are created by human beings in a city like Boston, and present that in a coherent way so that audiences can come to understand their world better.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.