Do women publish less than men in scientific fields? Turns out, scientists have been asking the wrong question.

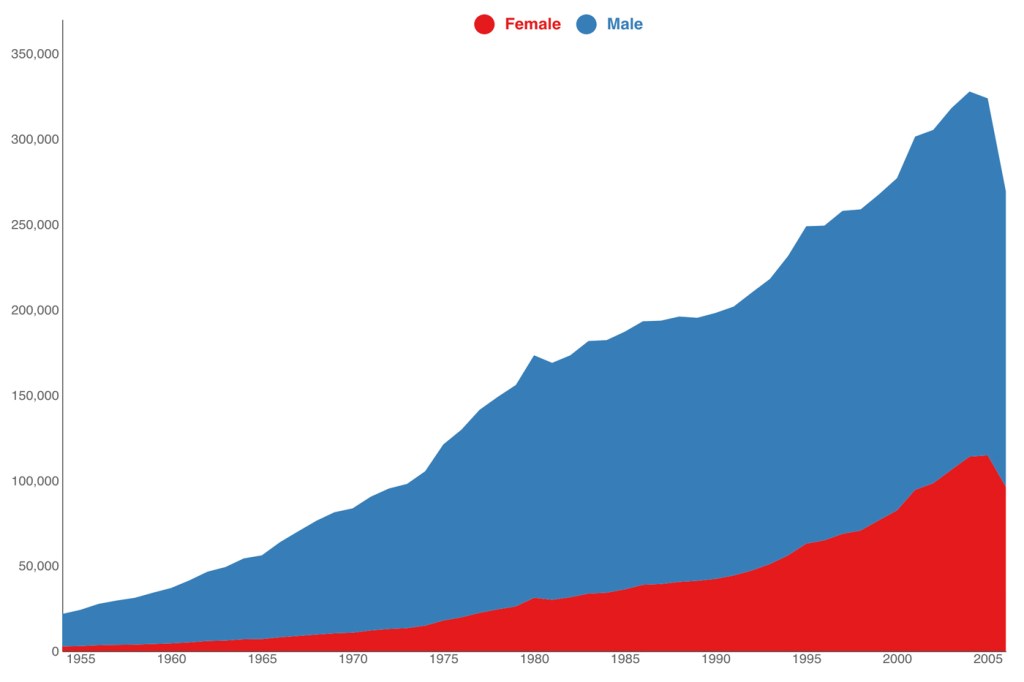

There is a persistent gender gap in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math: Over the last 60 years, across all disciplines, only 27 percent of research publications were authored by women. But the figure obscures important trends.

While in 1955 women represented only 12 percent of all active authors…

…that fraction steadily increased over the last century, reaching 35 percent by 2005.

Yet, these aggregate numbers hide considerable disciplinary differences: The fraction of women is as low as 15 percent in math, physics, and computer science, and reaches 33 percent in psychology. A team of Northeastern researchers sought to learn why.

There is a gender gap in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM): Over the last 60 years, across all disciplines, only 27 percent of research publications were authored by women, according to a new study by Northeastern researchers.

For years, scientists have puzzled over the persistent evidence that men publish more than women in STEM fields, and have posited myriad reasons for it. They’ve considered that perhaps women publish less because they have more responsibility to raise a family, or because they take more time off to have children, or because they have fewer resources at their disposal when they’re doing research, or for any number of other possible reasons.

But, these scientists may have been asking the wrong question.

It’s not that women publish less than men in their field, but that they leave their careers earlier and therefore have less time to publish, according to research by Northeastern professor Albert-László Barabási and colleagues.

Barabási is the Robert Gray Dodge Professor of Network Science and University Distinguished Professor of physics at Northeastern. He was joined by Junming Huang and Alexander Gates, both post-doctoral researchers at Northeastern, as well as Roberta Sinatra, an assistant professor at IT University of Copenhagen.

The researchers analyzed the complete publication history of more than 1.5 million scientists around the world, whose publishing careers ended between 1955 and 2010. They identified 412,808 female authors and 1,110,194 male authors and compared their productivity over the course of their careers.

They found that, year-to-year, women publish just as many papers as men: women average 1.33 papers per year, and men average 1.32 papers per year.

But, they also found that men tend to have longer careers. The researchers found that, on average, women in STEM fields spend 9.3 years publishing papers, whereas men spend 11 years publishing.

The gap persisted when the researchers compared by discipline, country, or affiliation, and has only been getting wider over the last 60 years.

Finding out what didn’t change between men and women (the average number of publications they wrote each year) helped the researchers discover what did (how long they tend to stay in their careers), Barabási says.

“The fact that women and men in the same fields have comparable annual productivity helped us unlock the roots of the increasing gender inequality—showing that a large fraction of it can be explained by the different dropout rates for men and women,” he says.

The researchers focused specifically on what caused the perceived difference in publishing volume among men and women, but they say more work will be required to determine why it appears women leave their careers earlier than their male counterparts.

“In many ways, this study is just the beginning of a journey, which will eventually offer a clear quantitative understanding of gender inequality and its roots in academia,” Barabási says. “We will need input from multiple disciplines and from the institutions to eventually eliminate it.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.