The cyberattack on New Orleans shows how vulnerable our cities are

New Orleans acted appropriately in quickly containing a cyberattack on the city’s computer servers, but more needs to be done in curbing the spread of such attacks on U.S. municipalities, says Stephen Flynn, the founding director of the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern.

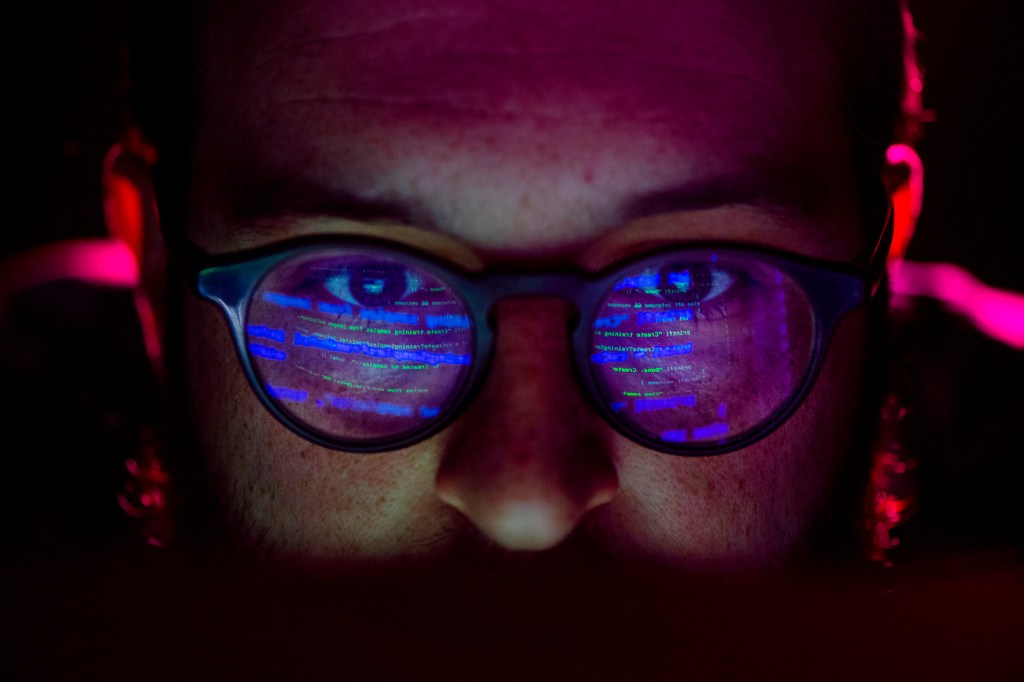

The city is the latest municipality to be handicapped by ransomware, a type of malware that threatens to release an individual or organization’s data on a computer or blocks access to it unless a ransom is paid. The December 13 attack forced the city to declare a state of emergency and shut down most of its computers after ransomware and a string of phishing emails were detected.

“I’m afraid this is happening with growing frequency across the country in no small part because it is very difficult, particularly for some communities, but also for virtually all city and state governments and others to keep pace with the sophistication of cyberattacks, and put safeguards in place to deal with this,” says Flynn.

Flynn’s organization has been working with the city of New Orleans on a proposal to make the city stronger against natural and man-made disasters. The Global Resilience Institute was actually in the process of filing a joint application with the city for a grant supporting a project that is intended to bolster the city’s infrastructure, including its energy, transit, and telecommunications systems, when the cyberattack occurred, says Flynn.

Local governments are easy targets, says Flynn, because they provide vital services and therefore are vulnerable to complying with ransom requests in order to get those services back up and running. They also often lack the resources and manpower to handle significant security threats.

“To some extent, there is a built-in vulnerability in most public entities at the local level that comes from limited resources relative to their information technology departments,” says Flynn. “Major corporations, or a major university like Northeastern, we make a significant investment in information technology safeguards, in hiring the top people who are working to come up with contingency plans. That’s a heavy lift for most communities, so it makes them very vulnerable.”

Still, gone are the days when it was acceptable to assign the responsibility of overseeing the security of an organization or company’s servers and databases to information technology departments. Flynn contends that in addition to IT departments, the onus falls on individuals to remain vigilant about opening or responding to emails that appear suspicious. Organizations would benefit from educating employees about the latest techniques that hackers employ to obtain personal information, he says.

“It’s in all our interests to get better at understanding this risk and managing this risk,” says Flynn.

It’s also unreasonable to expect that cyberattacks can be stopped once and for all, says Flynn. Cyberattacks are a drawback of our increasingly connected world, but organizations can take steps to safeguard their electronic data and stay ahead of security threats that often cause significant disruptions to the economy and to individuals’ quality of life.

“We rush ahead and want to get the benefit of connectivity, or the benefit of efficiency, and we’ll worry about the security afterwards. This is a fool’s errand,” he says. “Whenever we develop a new application, whenever we develop a new way in which we’re connected, we’ve got to think through the ‘what if?’ What if somebody wanted to cause mischief? That’s a different mindset than the one we’ve been operating on.”

Flynn worries that as cyberattacks become increasingly sophisticated, critical infrastructures, such as wastewater treatment plants and transit systems, will become targets for hackers.

“You could create oil spills, you can disrupt refineries, you can mess with transit systems and cause accidents,” he says. “These are real issues that these agencies are challenged by.”

While fail-safe security measures don’t yet exist, organizations and governments would do well to approach breaches by staying nimble in their response, isolating the attack, containing its potential damage, and recovering what is necessary as quickly as possible, says Flynn.

In New Orleans, it will likely take a few weeks for things to return to normal as officials go through and scrub clean nearly 4,000 computers at agencies across the city. But, Flynn predicts that the city will recover quickly, and without needing to pay a ransom.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.