Northeastern professor’s new public art installations throughout New England bring climate change home

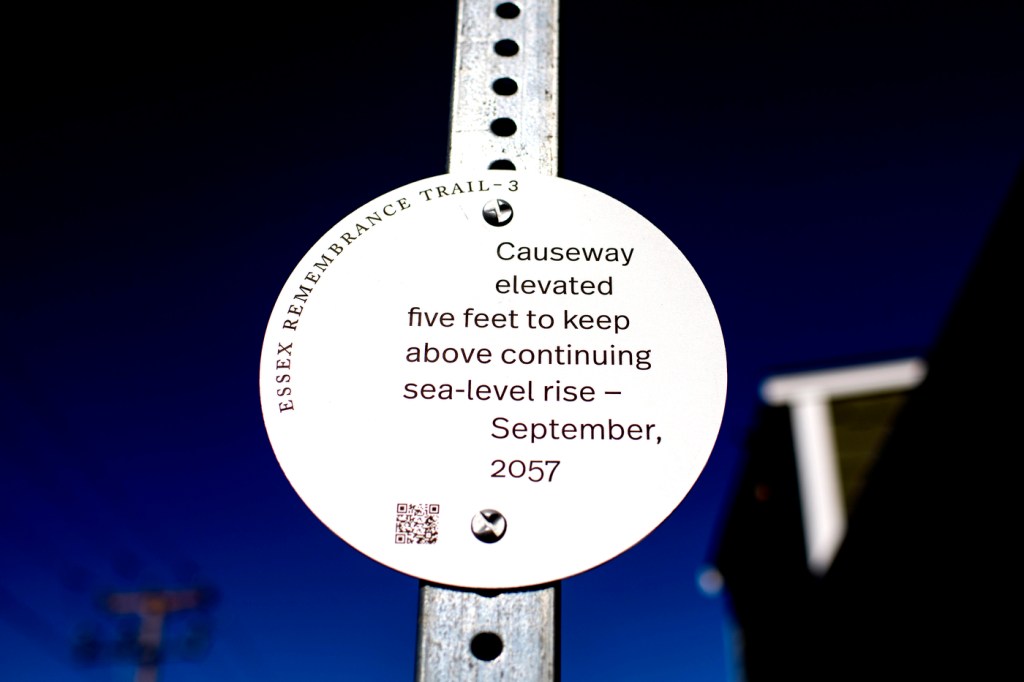

ESSEX, Massachusetts—The year is 2057. The main roadway in and out of this coastal town is raised five feet to keep it above the rising sea level.

The year is 2034. An underground channel that houses Ebben Creek in the marshlands of Essex is widened to accommodate a swelling ocean.

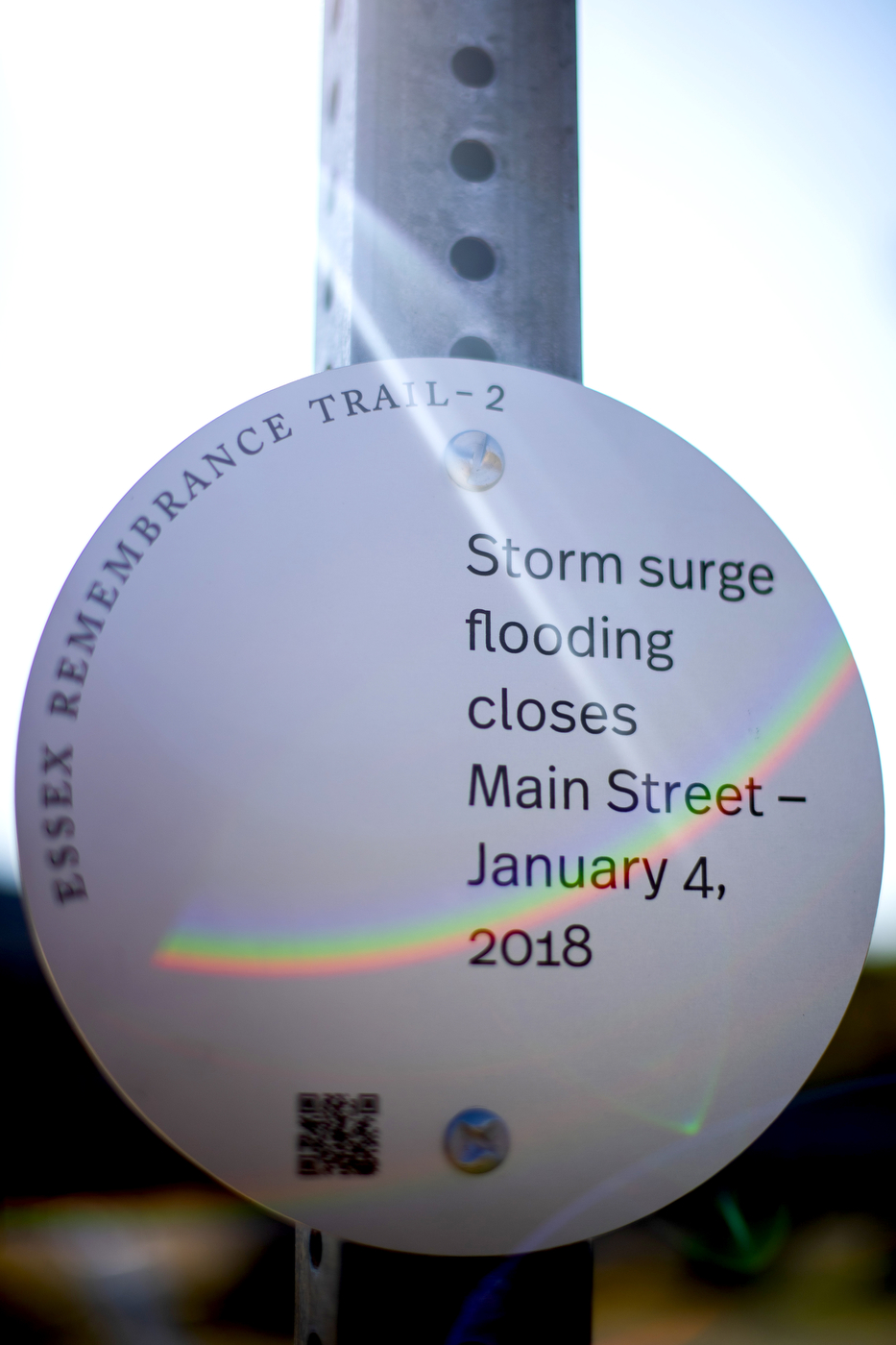

The year is 2018. Main Street is closed because it’s flooded by a storm surge.

This is the future (and recent past) of Essex presented by Thomas Starr in a new exhibit that is as much public art as public science.

It’s also the future predicted by the National Wildlife Federation, in its Great Marsh Coastal Adaptation Plan, a thick document designed to serve as a guidebook for coastal New England towns such as Essex, whose residents are anticipating and adapting to rising sea levels related to climate change.

Starr, a professor of graphic and information design at Northeastern University, created a series of small signs that describe how the landscape might change in the next decades. The signs, (six in all) that were installed around town in the specific places they describe, were written with plain, matter-of-fact language drawn directly from the coastal adaptation plan, Starr says.

Another similar installation in Durham, New Hampshire, and one planned in Cambridge, Massachusetts, are similarly site-specific. They’re designed to bring the huge, often nebulous problem of climate change home, Starr says.

“So much of what we read about climate change has to do with the Greenland ice sheet melting, or polar bears starving; things that are dire but don’t necessarily affect us directly,” he says. These signs, then, are designed to be reminders of how a warming climate could affect us directly.

Each sign also includes a special code that, when scanned with an internet-enabled phone, directs the viewer to the municipality’s climate report, where all Starr’s information comes from.

“I met with so many municipal leaders who said, ‘We have these studies, but not enough people are looking at them,’” Starr says. “The whole idea here was to engage citizens with what their towns are doing.”

And it’s not just Essex, Durham, and Cambridge that have such studies—Starr sees potential for this project to pop up in towns across the United States, and perhaps around the world.

“All climate change is going to be local,” he says. “What I’m hoping is that it finally sinks in for folks that, ‘This is going to affect me where I live,’ and take action from there.”

For media inquiries, please contact Mike Woeste at m.woeste@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.