Northeastern University looks back at the moon landing 50 years later: Shooting for the Moon

Shooting for the moon

Saturday, July 20, marks the 50th anniversary of the first landing on the moon. Every day this week, News@Northeastern will look at the technological breakthroughs, the political decisions, and the feats of daring that made the landing possible; the lunar landing itself; and what the future might hold for space exploration. Northeastern’s Archives and Special Collections is the exclusive home of The Boston Globe’s Library Collection, and we’ll use those images to highlight the space program and the university’s role in space exploration.

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, President John F. Kennedy, and Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Glenn T. Seaborg, during a visit to the Los Alamos National Laboratory inDecember 1962. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

It was 1961 and the United States was in the uncomfortable position of playing catch-up with the Soviet Union.

Three weeks after the Soviets sent Yuri Gagarin on a successful orbit of Earth, the United States sent the first American into space. Alan Shepherd’s Friendship 7 capsule arced through sub-orbital space before returning safely to Earth—an impressive achievement, but one that fell short of the mark the Soviets had set.

But President John F. Kennedy and his advisors had a plan. In a speech before Congress, Kennedy outlined the ambitious goal of putting a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

“No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space,” Kennedy said. “And none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

Shepherd’s 15-minute flight was part of Project Mercury, NASA’s first human spaceflight program. The project wrapped up in 1962 after a total of six crewed missions into space, including John Glen’s successful orbit of the Earth.

Northeastern President Asa Knowles and two students examine a Mercury capsule at a NASA exhibit in Cabot Cage in April 1964. Image Northeastern University.

NASA had a lot of questions to answer before it could send astronauts to the moon. Were there harmful effects from being in space for too long? Could astronauts work outside their capsule? How would two spacecraft detach from each other and later reconnect in flight? Project Gemini, which included a series of two-man space flights, found the answers.

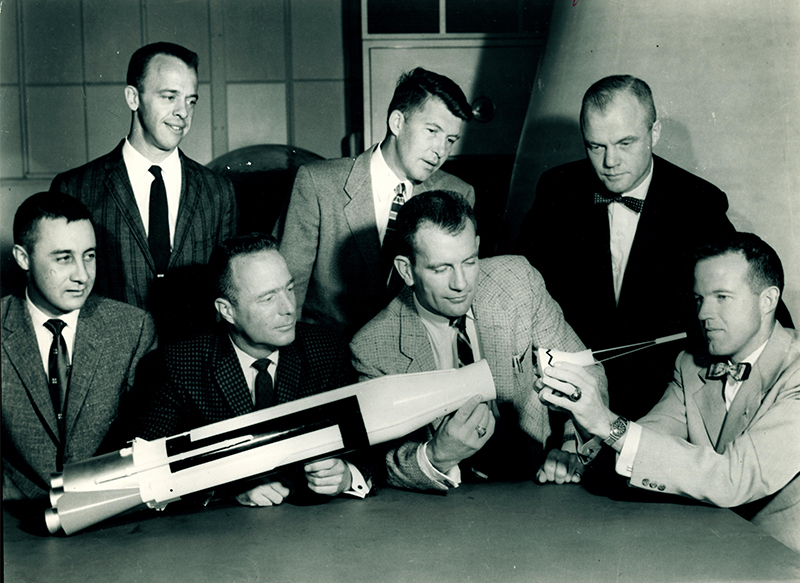

The Mercury Seven. Left to right: Virgil Grissom, Alan Shepard, Malcolm Carpenter, Walter Schirra, Walter Slayton, John Glenn, and Leroy Cooper. Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

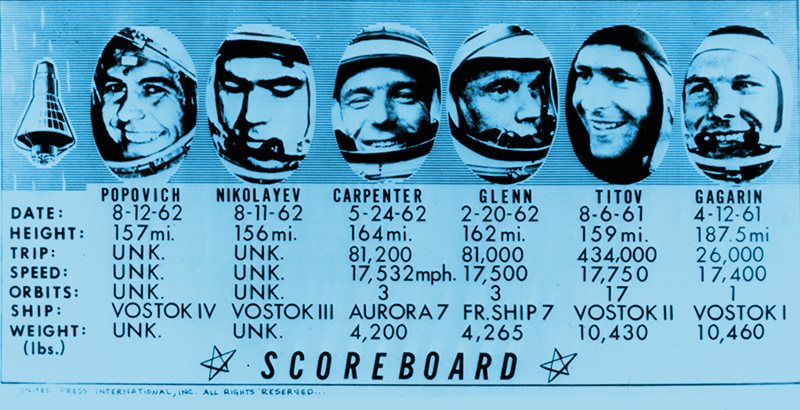

Keeping score of the Space Race in August of 1964. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Meanwhile, the Soviets were making strides of their own. Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space in 1963. And work continued on the Luna program, which had already successfully sent Luna 2 to crash on the surface of the moon and scatter a payload of Soviet medallions, making it the first human-made object to reach another celestial body (and the first to litter there).

Mercury-Redstone. Image courtesy of NASA.

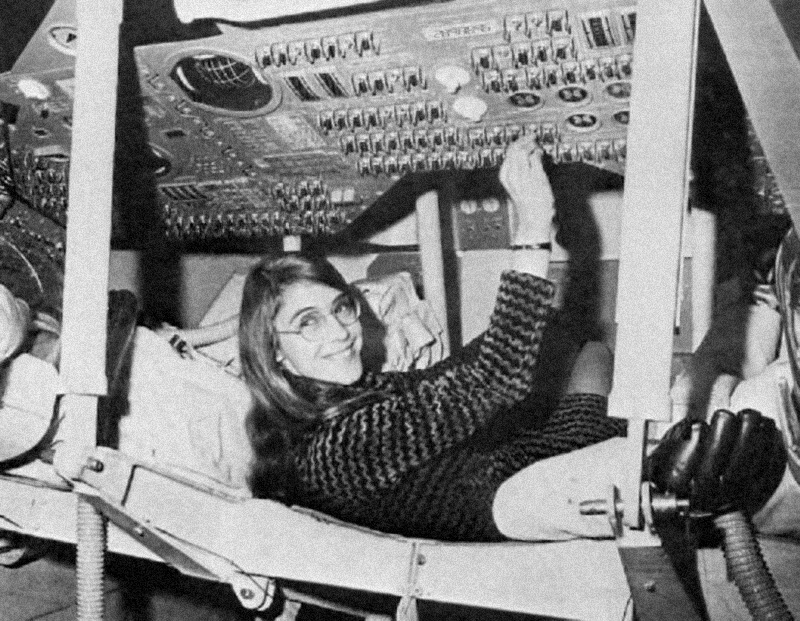

Margaret Hamilton, lead Apollo flight software engineer, tests the Apollo Command Module circa 1965. Image courtesy of NASA.

As NASA was learning how astronauts could live, work, and maneuver in space, the project that would eventually take humans to the moon was already underway. Project Apollo called for a three-person spacecraft made up of three sections: a command module (where the crew lived), a service module (holding fuel, maneuvering rockets, and life-support systems), and a lunar module (which would bring two astronauts to the moon’s surface and back). All of this would be mounted on the nose of a large, multi-stage rocket intended to propel the craft out of Earth’s atmosphere.

The return trip would involve plunging the blunt, cone-shaped crew compartment through the atmosphere—employing some of the heat and gas produced to act as a cushion—and then slowing the craft down with parachutes before it reached the ground.

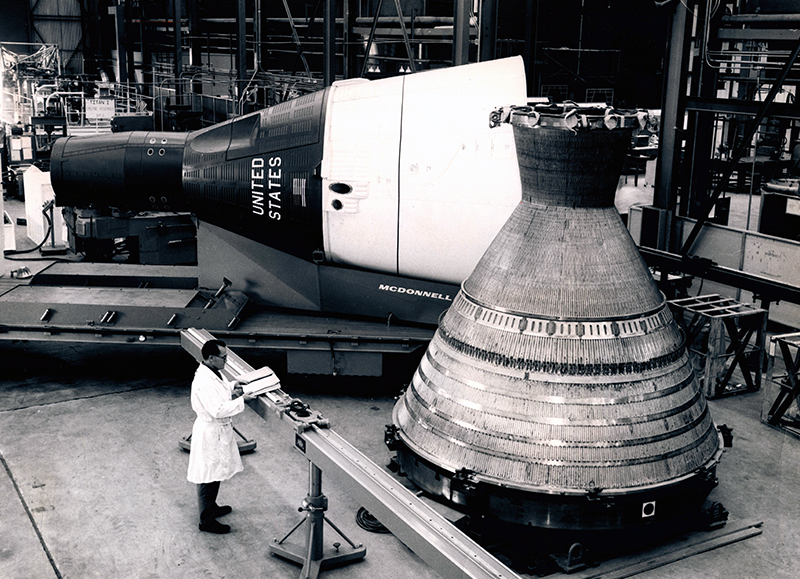

Thrust chamber section of the new M-1 liquid hydrogen rocket engine (foreground) looms almost as large as the two-man Project Gemini space capsule in Sacramento, California, in December 1964. Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Pictures of the recovery of Gemini 6 by the USS Wasp are broadcast live on television for the first time in December 1965. UPI/Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Project Apollo began with uncrewed tests, but in December of 1968, the astronauts on NASA’s Apollo 8 mission had successfully orbited the moon and returned safely.

Communications satellite Intelsat 2 being readied for deployment in Earth orbit in September 1967. Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

There’s a common misconception about the 1960s Space Race: that it was another arena in which the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union played out, pitting two countries against each other in a bitter race to outer space. This is only partially true…the competition wasn’t bitter, and Sputnik didn’t come out of nowhere.

–Mai’a Cross

Associate Professor of Political Science & International Affairs

Northeastern University

In May 1969, astronauts Thomas Stafford, John Young and Eugene Cernan flew the Apollo 10 mission: a full dress rehearsal for the moon landing. Their lunar lander, nicknamed Snoopy, descended to just eight miles above the moon’s surface before returning to Charlie Brown, as the orbiting modules were called.

The only thing left was that one small step.

Flight communications at Cape Kennedy, Florida in December 1965. Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Network pool monitoring room at Cape Kennedy, Florida in December 1965. Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library Collection at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

- The space age takes flight

- Shooting for the moon

- After the moon

- Mars and beyond

- July 20, 1969