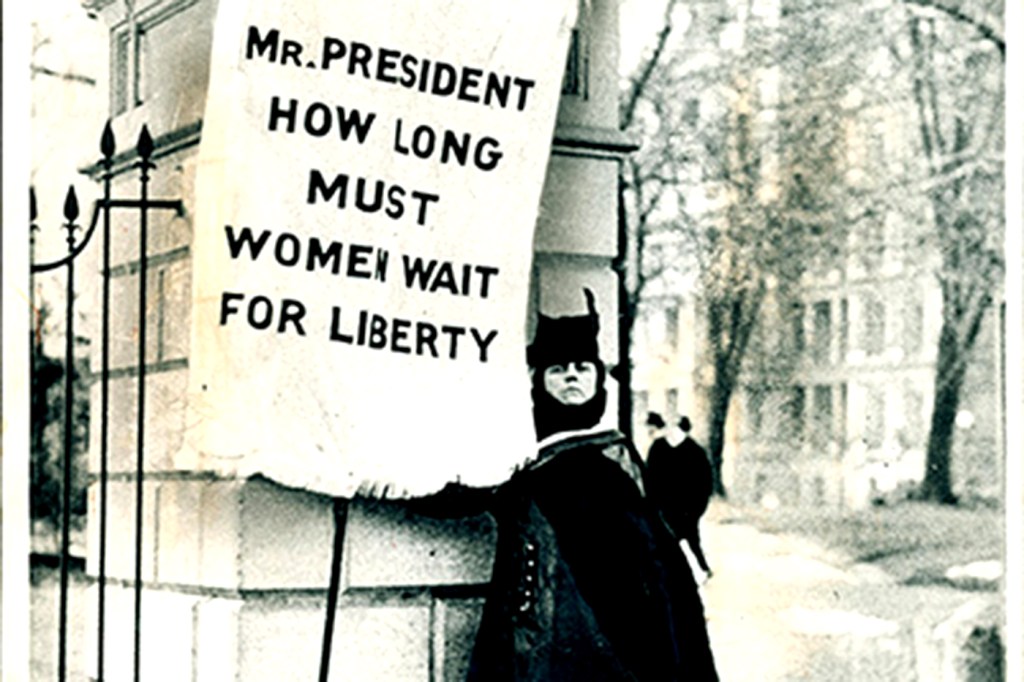

How suffragist Alice Paul outmaneuvered President Woodrow Wilson to create the 19th Amendment one century ago

On June 4, 1919, the United States Senate passed and sent onto the states for ratification a law to grant voting rights to women. The 19th Amendment, which would be made official the following year, was pushed through by President Woodrow Wilson, who called a special congressional session.

Alice Paul, a Quaker from New Jersey, was the unlikely leader of the women’s suffrage movement. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

But Wilson’s support came reluctantly. He capitulated after years of protests engineered by 34-year-old Alice Paul, the unlikely leader of the suffrage movement. Paul and her followers endured imprisonment, hunger strikes, and beatings before creating the public outcry that forced Wilson to see it their way.

Journalist Tina Cassidy, a Northeastern graduate and author of the new book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote, says that the nonviolent strategy of women’s suffrage served as an example for future political causes.

“Gandhi witnessed one of the nonviolent protests that Alice Paul was involved with in England, and he was certainly inspired by these women,” says Cassidy, who is now the chief marketing officer for WGBH, a publicly funded media company in Boston. “Nonviolent protest was also foundational to the civil rights movement in America. Their principles show us that you can affect change without hurting other people.”

Cassidy shared her insights on the 100th anniversary of the congressional action that enabled women to vote.

Who was Alice Paul, and how did she become a suffragist?

Alice Paul was brought up in New Jersey on Quaker values, which are based on equality, racial and gender equality. As a young woman, she went to England to study social justice. It was there that she ran into the Pankhursts (Emmeline and Christabel), who were leading the movement in the United Kingdom to win voting rights for women.

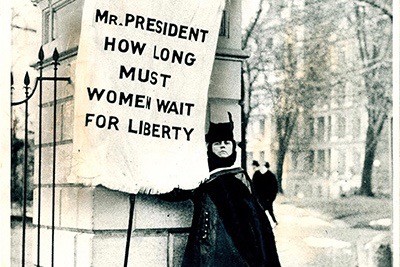

Women staged protests throughout the United States with the goal of pressuring Woodrow Wilson. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

She was so horrified by the way they were treated by the audience, with people shouting, and singing over them, and throwing things—she’d never seen people treated that way. She was so captivated by this moment that it totally changed her life. She decided to join the Pankhursts’ movement in the U.K. for the vote, and she learned everything that she possibly could from their social change movement, and then brought it back to America.

She realized that being polite and asking sweetly for the right to vote was not getting women anywhere, and that radical tactics were necessary. For a woman that might mean standing on a street corner holding a sign, or speaking out from a stage—these were considered radical acts.

While in prison in the U.K., she learned that hunger strikes were an effective way to get attention and to bring sympathy to the cause. But I think she also became hardened, and really understood that she would have to develop a protective shell to get through the work, and that it was going to involve a great deal of resilience, and determination, and persistence.

Alice Paul went on hunger strikes while in prison, which led to numerous force feedings. How were these feedings administered a century ago?

It was terrible. It was horrific. The prison wardens would strap her hands down, and they would put a towel or sheet over her head and neck to pin them back. And then they would take a tube and put it up her nose; and with a funnel at the top of it, they would slide milk and eggs down the tube. This did not work smoothly. It was often a glass tube, and she suffered abrasions. She would vomit up the food. She also fought at having the the tube inserted and was wounded by that.

It was torture, and it brought sympathy to the movement. It really backfired on officials who insisted on the forced feedings.

She suffered her whole life from the after-effects. It seems as if her sense of taste and smell were damaged. If you can’t smell food, it’s not always appetizing. So she was always frail and never really ate enough, and she also had some digestive troubles that could have been related.

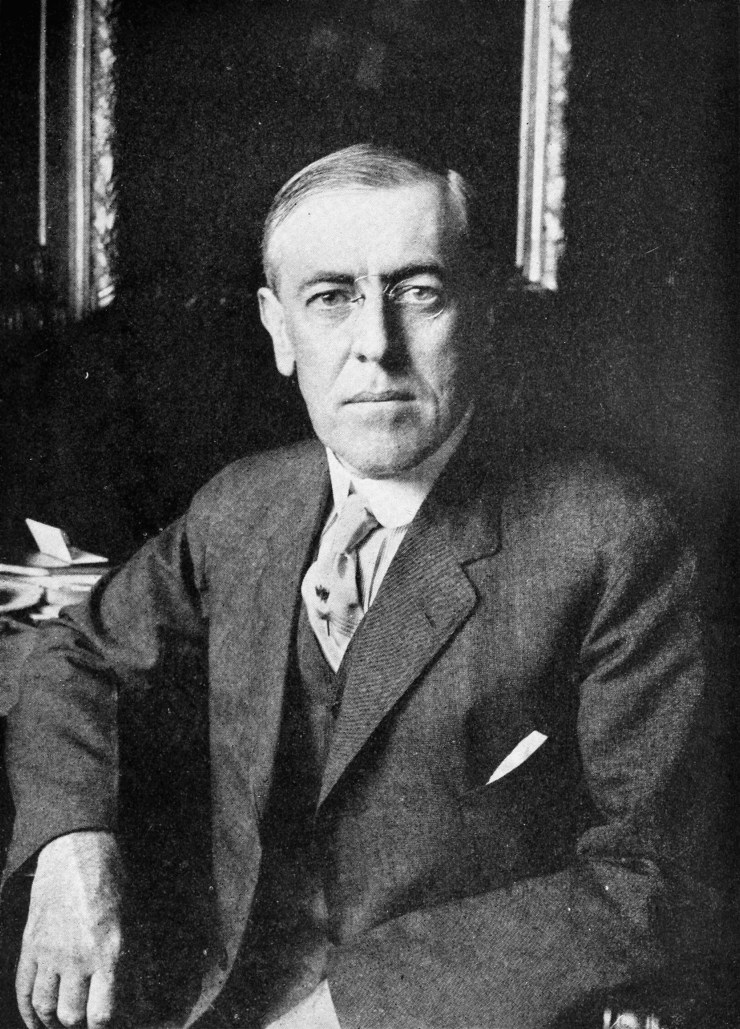

What role did Woodrow Wilson play in the struggle, and what did it reveal about him and his presidency?

President Woodrow Wilson was opposed to equal voting rights for women—until the suffragists boxed him in politically. The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives.

As a professor at Bryn Mawr College, he thought it was ridiculous to have to teach women, he thought it was beneath him. He also believed that suffrage was the root of all evil.

Woodrow Wilson considered himself a moral president, and yet he did not believe that women should vote. He called himself a moral president, and yet he segregated the civil service in one of his first acts as President.

He created [modern American] segregation. He said that African-Americans and white Americans could not eat at the same table in a federal building; that black customers at the post office would have to go to a special window and be served by black employees; that if you wanted a government job, you had to submit a photograph with your application so that the government could know if you were black or white. That is a legacy that has greatly damaged the nation.

He was so focused on foreign affairs and the Great War that he did not pay enough attention to the needs at home; many of those needs were about inequality in America. He turned his back on that and actually inflamed it in many ways.

Did Alice Paul and her group engage personally with Wilson?

It is a very odd thing to consider that back then, in the early 19-teens, you can literally walk in the door of the White House and ask to meet with the president. And this was in part Woodrow Wilson’s doing: He wanted a transparent government.

The Boston Globe via Northeastern University archives

So these women had many, many meetings with him, especially during the first four years of his presidency.

Unfortunately, as great as that might be that they had access to the President, meeting with him so many times had no effect.

His answer was always the same. I’m too busy. This is unimportant. Giving women the vote is at the bottom of the list of things that I need to focus on. He had his own agenda, and he was sticking to it. And he was really unwilling to change in some ways. He was also affronted by the fact that these women had the audacity to ask for voting rights.

Wilson’s stubbornness was supported by his wife.

The second First Lady, Edith Wilson, shared his view, even though she was a successful and independent businesswoman in Washington before he met her. I just think it was a major change for people to get their head around, that women should be allowed to vote.

How did World War I influence the voting rights movement?

World War I absolutely changed how lots of people viewed the women’s movement. Initially, people who considered themselves patriotic thought it was deplorable that women would protest outside the White House during the war. But as the war went on, people began to understand that we couldn’t set ourselves up as a beacon of democracy when we did not have true democracy in America.

I think Americans really understood the hypocrisy, that so much was being asked of women, they were sacrificing their own sons and husbands on the battlefield, and it wasn’t right that they didn’t have a say in any of it at the ballot box. So the war loomed over the entire movement.

How did World War I influence the voting rights movement?

Eventually public opinion came around, and more people agreed with the idea that women should vote. Wilson was a lame-duck president, he was boxed into a corner, and he believed that his Democratic Party would lose if they opposed women’s suffrage. It was a political decision on his part; it was not a moral epiphany. He just said, fine, there’s enough support, let’s go ahead and allow Congress to pass it and the states to ratify the amendments.

Alice Paul [1885-1977] lived to the age of 92. What became of her after her big victory?

What’s amazing is that after the 19th amendment was ratified, Alice Paul could have hung up her hat, put her feet up, and had what we might consider a normal life. Instead, she went to law school, and just three years later she wrote the Equal Rights Amendment. She dedicated the rest of her life to legislation that would promote equality. It’s astonishing to think that giving women the vote was not enough for her.

Alice Paul was a very slight, quiet, reserved woman, and the fact that she could transform herself from that humble beginning to become the leader of a movement that would enfranchise half of the American population is profound. There are lessons in there for all of us.

For media inquiries, please contact Marirose Sartoretto at m.sartoretto@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.