Recounts almost never lead to election reversals. Here’s why they matter.

The midterm elections earlier this month resulted in historical voter turnout and a deepening of America’s polarization. Major races in Florida and Georgia remained undecided for nearly two weeks, while election recounts fed national rancor and controversy.

Recounts are exceedingly rare in the United States. Of the 4,687 state-wide elections held between 2000 and 2015, only 27 yielded recounts. And in only three cases were the original results overturned.

The unlikely potential of reversing the result is not the main reason for seeking a recount, said Daniel Medwed, University Distinguished Professor of Law and Criminal Justice at Northeastern. The ultimate purpose is to count every vote, regardless of the outcome, and to thereby protect the American institution of elections.

“We’ve heard lots of stories about potential improprieties in Florida,” Medwed said. “Even if it’s not outcome-determinative, it’s important to litigate as a matter of principle to expose the problems, to restore confidence in the right to vote for people.

“There are practical reasons to go for a recount. But they’re outweighed by the more principled reasons, which is to make the system as fair and equitable as possible. And sometimes the only way to do that is to expose the flaws and fight about them.”

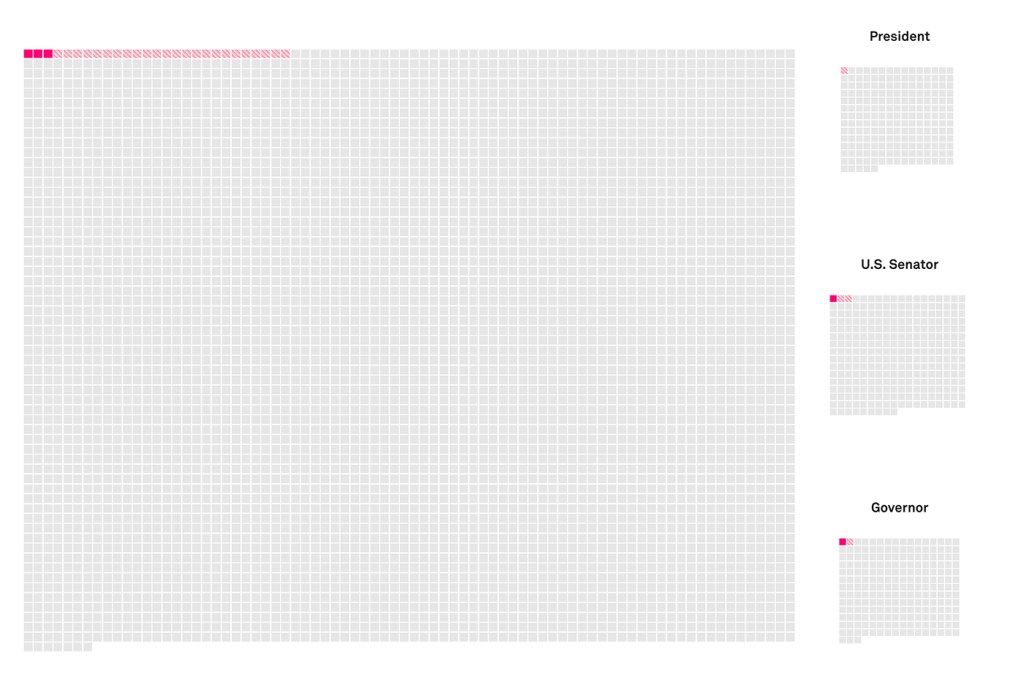

In Florida, the election-night results for governor and United States senator both fell within a margin of 0.5 percent, thereby leading automatically to recounts by state law. The senate race, which pitted Republican Gov. Rick Scott against incumbent Bill Nelson, ended Sunday after a hand recount showed that Scott had edged out Nelson by 10,033 votes.

The race for governor of Florida ended Saturday, when Democrat Andrew Gillum conceded to Republican Ron DeSantis. Gillum, the mayor of Tallahassee, had reportedly considered a lawsuit to contest the results.

President Donald Trump responded to the recounts last week by accusing Democrats of trying to “steal” the elections. “We are watching closely!” he tweeted. Scott joined him in warning of electoral fraud, without the backing of evidence.

Such questions over the integrity of the ballot box will have little negative impact on the overall health of the electoral process, predicted Northeastern political science professor William Mayer.

“If anything, it will at least satisfy some people that Scott honestly won,’’ said Mayer. “Politics is more polarized these days. There’s less goodwill between the parties. So this is merely one reflection of that.”

The partisan bickering has brought back memories of the 2000 Florida recount, when the presidential election was hanging in the balance. George W. Bush ascended to the presidency by a margin of 537 votes in Florida after the United States Supreme Court stopped a recount by a 5-4 vote along partisan lines.

“The good news is it’s not that close,” said Mayer of the senate election in Florida. “And of course there’s a huge difference between gaining and winning one more senate seat versus gaining or losing the presidency.”

In Georgia, Democrat Stacey Abrams conceded the race for governor Friday night. Her party had been hoping to pick up votes by recount in order to force a Dec. 4 runoff. Democrats have complained that newly-elected Gov. Brian Kemp, in his role as secretary of state, has purged 1.4 million people from the voter rolls—70 percent of them African-Americans.

In the context of unverified accusations of rigged elections, evidence of voter suppression, and the influence of Russian hackers on the 2016 presidential election, Medwed insists that Democrats have no choice but to contest the results.

“We’re living in an era when our core system of voting is under attack,” Medwed said. “There’s a sense that people are playing fast and loose with the rules domestically, and that we’re under attack from a foreign rival.

“It’s often said that sunlight is the greatest disinfectant. I think litigation is sometimes a means of achieving sunlight and exposing some of the problems, even though it does often create ill will. I’m not always a huge fan of litigation to resolve disputes. But in this case, our system is broken down so much that I think it’s the only way to do it. The only way to improve things is to fight.”