He wants to put Puerto Rico, devastated by Hurricane Maria, back on the (nano) grid

Three days after power had been restored to their home in Puerto Rico, Eugene Smotkin’s wife had a stroke. Seven days later, Hurricane Maria hit.

The entire island, 3.4 million people, lost power as a result of the September 2017 storm. After two weeks of charging cell phones with a car battery, Smotkin and his wife were able to get on a humanitarian flight to Boston.

“She’s nearly fully recovered,” Smotkin said. “We were lucky.”

Many people weren’t as fortunate, especially in the countryside. Recent estimates put the death toll at over 1,400, as people struggled to survive without electricity for months.

Now Smotkin, a Northeastern professor of chemistry and chemical biology, is working to create a system to prepare vulnerable Puerto Ricans for the next time the electrical grid fails.

Smotkin grew up in Puerto Rico and lives in Old San Juan when he isn’t teaching. He envisions what he calls “nanogrids”—small clusters of houses sharing power from solar panels—provided at little to no cost to the people still rebuilding their lives following Hurricane Maria.

“My goal would be that they would still use the grid, but when the grid fails, which is frequently, they have backup power,” he said.

If Honda and Toyota cooperated, I could light up a good fraction of Puerto Rico.

Eugene Smotkin, professor of chemistry and chemical biology

Typically, the concern with such solar setups is the cost of the materials. While solar panels have been getting cheaper, the system also requires battery banks to store excess energy for those times when the sun isn’t shining.

“When you’re talking about an environment where people are near poverty, you can’t expect to sell them expensive batteries that are $300 apiece,” Smotkin said. A nanogrid would need a whole bank of these batteries.

But Smotkin doesn’t want to use new batteries. He’s planning on intercepting batteries that are about to be recycled.

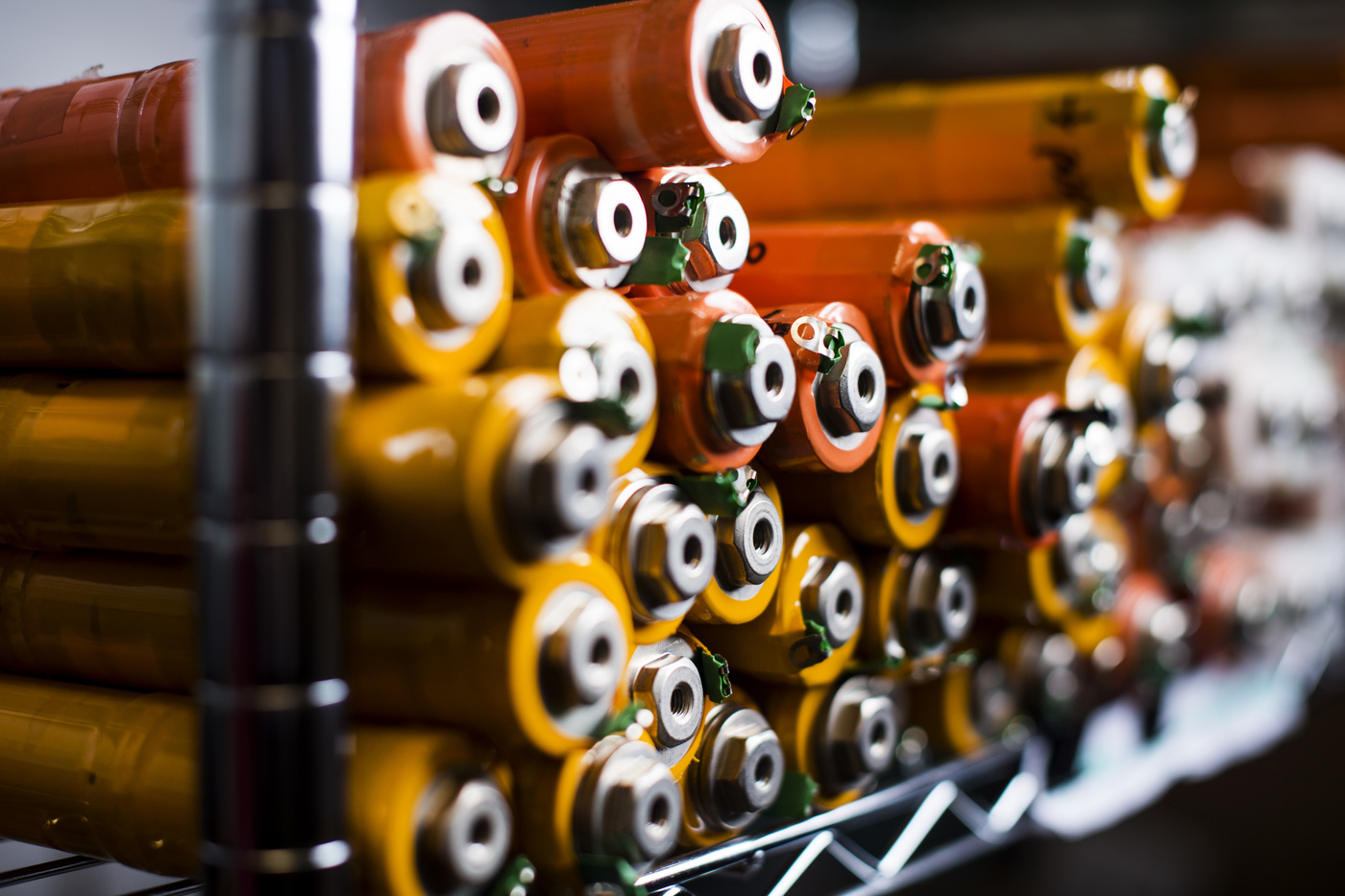

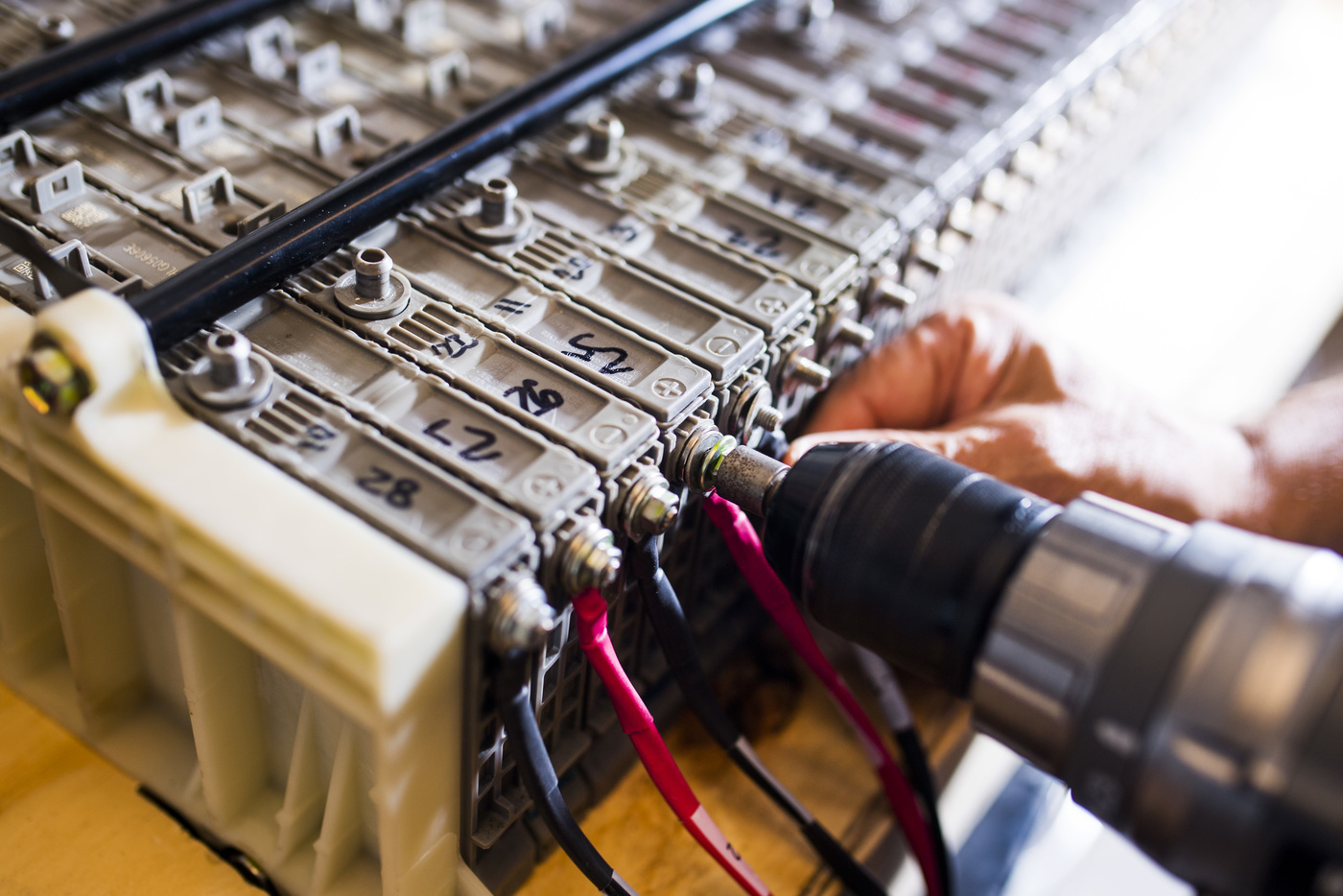

In recent years, Smotkin’s private company, NuVant Systems, has focused on restoring batteries for hybrid cars. When the vehicles are in use, they are constantly discharging and recharging their batteries in small amounts. This eventually causes the batteries to lose a large portion of their capacity and need to be replaced.

With a cadre of Northeastern co-op students and graduates, NuVant created equipment to essentially exercise these batteries and restore them to like-new condition. The reconditioning process forces the battery through a series of deep discharges, retraining it to use its full capacity.

For the most part, these batteries have been going back into hybrid vehicles. But some of the reconditioned batteries aren’t quite good enough. They can still store plenty of energy, Smotkin said, but they can’t generate the large amounts of power that a car requires.

Instead of sending them to be recycled, Smotkin wants to give those batteries a new job storing power in Puerto Rico.

“There are a ton of these batteries that are available,” said Alston D’Costa, a graduate student in Northeastern’s energy systems program. “We can use their capacity, because they’re not dead.”

D’Costa started working on the nanogrid project after taking Smotkin’s course on batteries for energy systems this past spring. He sees it as a sensible failsafe for current power systems.

“If you have a system like this, you’re always protecting your citizens,” he said. “That’s what draws me to it. It’s assuring power to people.”

Smotkin’s final assignment for the course was to design a nanogrid for use in Utuado, a municipality in central Puerto Rico that was devastated by Hurricane Maria. Power has been restored, but the electrical system is still extremely vulnerable.

“They just propped the poles up and strung wiring along,” Smotkin said. “You see wiring that’s maybe 20 feet above the street level. It’s a very precarious situation. They have power failures weekly.”

Smotkin has been visiting Utuado to determine the residents’ needs. He hopes to deploy the first nanogrids there. “The farms and residents that I’ve visited, they’re all excited about the possibility,” he said.

He is currently in the process of setting up a nanogrid to test in his own home in Old San Juan. But before he can deploy this setup on a larger scale, he is going to need a lot of batteries. Smotkin hopes to find a way to persuade car manufacturers to send their almost-dead batteries to him, instead of taking them apart for recycling. Then he and his students could recondition them and start installing nanogrids.

“If Honda and Toyota cooperated, I could light up a good fraction of Puerto Rico,” he said.