Drones for research: Explaining Northeastern’s policy

As drones grow in popularity, so too is the range of ways society is using them. They’re being deployed to deliver goods and take amazing photos and videos. Researchers, including those at Northeastern, across many disciplines are also increasingly turning to unmanned aerial vehicles to advance their work.

Last semester, Northeastern established its policy on drone use and formed the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Review Board to review, advise, and approve drones use on campus and help guide researchers through the complexities of this process. The review board is comprised of faculty members as well as representatives from NUPD and the offices of risk management, the general counsel, environmental health and safety, and the provost.

“Our policy is designed to enable more research and more activities using drones on our campuses,” said Taskin Padir, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, who chairs the review board. “We are really hoping Northeastern will have a strong research program in drones. It’s one area of technology that’s growing immensely.”

Processes and guidelines

Researchers must follow certain university and Federal Aviation Administration guidelines to safely and legally use Unmanned Aircraft Systems, a.k.a. drones on campus. When flying a drone of any size, for any reason, either indoors or outdoors on university property, or for any university purpose, researchers must apply to Northeastern’s review board for approval, Padir said.

Our policy is designed to enable more research and more activities using drones on our campuses.

Taskin Padir, Associate professor, chair of the review board

Northeastern’s policy states that UAS use for any university activity or on any of its campuses is not permitted without prior written consent from the UAS Review Board. The board reviews drone-use applications, and when granting approval, it may impose specific conditions not outlined in the application, such as the defined area of use and timeframe. The university’s policy covers any use of drones on campus, whether it be for research, recreational, or commercial purposes. University-approved drone use must also comply with federal and local laws.

To fly a drone outdoors for recreational or commercial purposes under the FAA’s Small UAS Rule (Part 107), you must register your drone and get a remote pilot certification. Under the Part 107 rules, drones must weigh under 55 pounds and be flown at or below 400 feet high. Users must also receive an FAA waiver before flying a drone in controlled airspace near airports, and drones must also be flown within visual line of sight.

Once UASRB and FAA approval is secured, researchers may begin use of the aircraft according to the specifications contained in the approved application, the UAS Policy, the FAA Waiver, and all applicable rules and regulations. Any changes to the information contained in the application must be approved through the application change process.

Northeastern researchers using drones

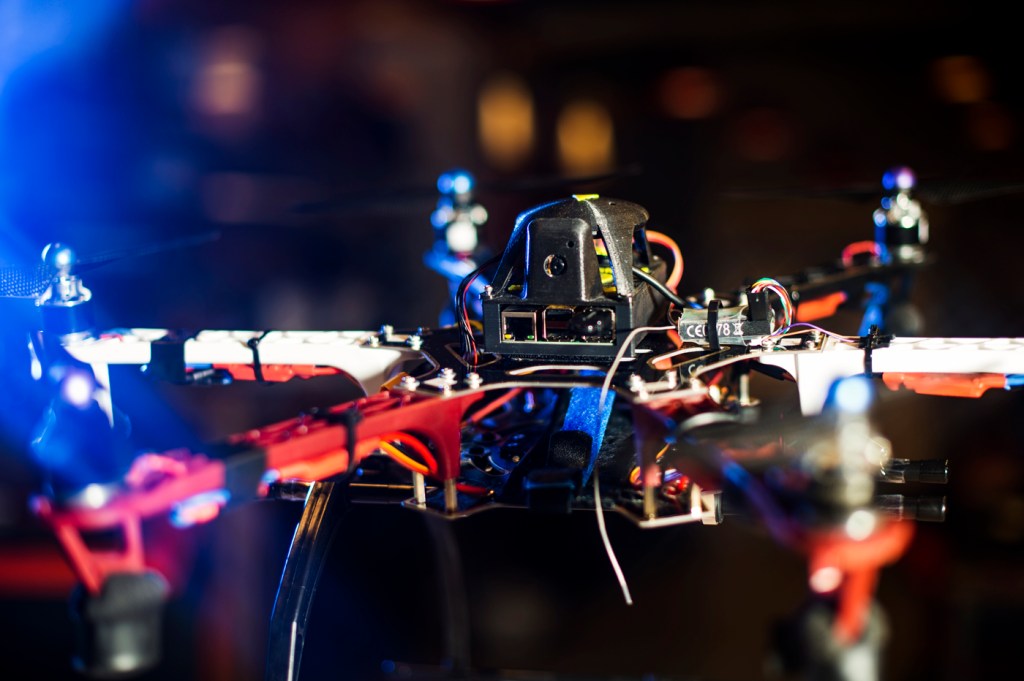

Padir, for his part, is using drones in his own research. He’s teamed up with colleagues Jerry Hajjar and Peter Boynton to develop drones that scan for infrastructure damage to prevent further devastation after extreme events. He explained that drones can help spot cracks, fractures, and other structural vulnerabilities that are often inconspicuous and may appear innocent to the untrained eye. The team’s ultimate vision is that a swarm of UAVs could assist engineers in damage inspection, but right now the researchers are still refining the hardware and algorithms so the UAVs know what to look for.

Another professor, Brian Helmuth, is using aerial drones to map the topography of shorelines. The goal is to better understand how intertidal communities recover following heat waves. He explained that at low tide, marine animals such as barnacles and mussels seek shelter from the sun in tiny crevices along the shoreline and beach. They use drone photos to build 3-D models of shorelines in order to study how these natural systems respond, particularly during heat extreme events, and determine whether they can mimic the resilience of natural shorelines using artificial structures, in scenarios where seawalls are necessary for protection of property and life.

Helmuth’s lab is collaborating with scientists in Israel on the project. They have already used drones to study shorelines in the Gulf of Maine and Israel, and they are seeking a FAA waiver to use drones off the coast of Nahant, Massachusetts, at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center. Drones, he said, dramatically decrease the time and manpower needed to photograph these shorelines; in lieu of drones, to study the Marine Science Center shoreline the team has walked up and down the beach taking photos atop stepladders.

“During extreme heat events, there are some areas where animals can ride it out and then repopulate. But one thing we don’t know much about is how the role of small-scale crevices in terms of these animals’ survival,” Helmuth said. “Using drones, we’ve been able to make really detailed maps reconstructing these shorelines.”