Stony coral tissue loss disease is sweeping through Caribbean reefs. Can these students find the answers?

BOCAS DEL TORO, Panama—Alison Noble’s scuba tank drops over the side of the boat with a deep splash. After pulling on two long white fins and a mask, she follows her tank into the water, fastening the straps and buckles that secure it around her neoprene wetsuit.

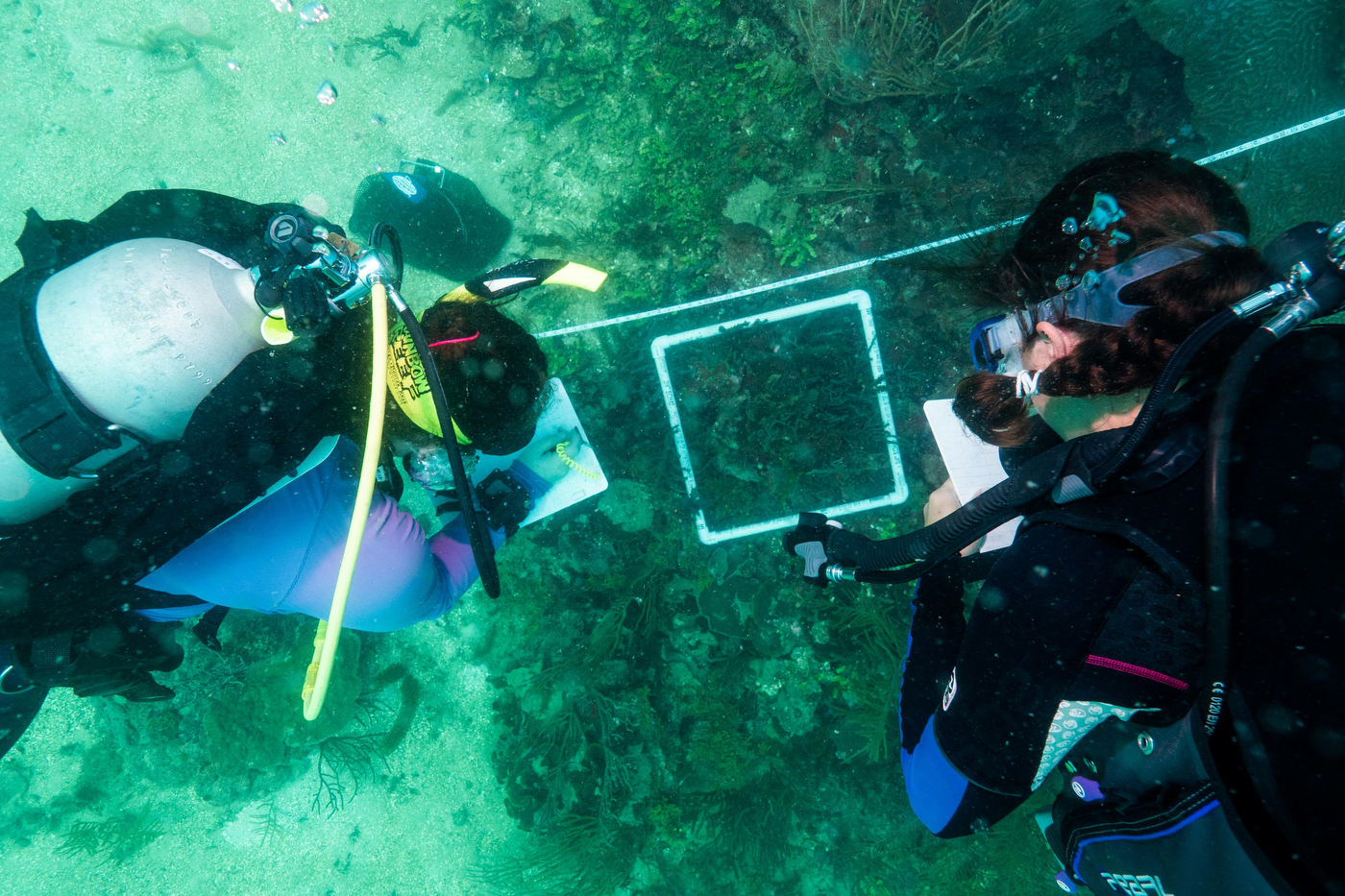

Noble checks with her buddy, takes a breath from her regulator, and the two divers descend side-by-side, letting air out of their buoyancy control devices to sink towards the bottom, towards the reef. Noble lays down a long tape measure, known as a transect among scientists, to mark their research area, and starts swimming. She’s looking for a bright white blaze, a malevolent stowaway on the currents that wash over these reefs.

It’s called stony coral tissue loss disease, a plague that’s sweeping down the Caribbean from reefs just off of Miami, Florida.

Noble, a fourth-year marine biology student at Northeastern, is one of 13 students surveying a coral reef off the coast of Panama for signs of the disease as part of the Three Seas program, a year-long intensive marine biology curriculum. She’s surveying the reef in Panama as part of the Biology of Corals class, watching for what could be the newest outbreak of stony coral tissue loss disease.

The Caribbean is the third “sea” of Three Seas. The students also study the Salish Sea from a facility near Seattle, and the Gulf of Maine from Northeastern’s Marine Science Center in Nahant, Massachusetts.

Along her transect, Noble takes note of the species and health of every coral she finds. Corals are made up of hundreds or thousands of small organisms called polyps, which live as a single colony. Each polyp is filled with colorful plankton called zooxanthellae, which photosynthesize and pass food on to their polyp hosts. When a coral dies, it turns a harsh white as it loses its zooxanthellae and reveals its limestone skeleton.

First seen in 2014 but not studied until 2017, stony coral tissue loss disease threatens twenty species that comprise the heart of the Caribbean’s coral reefs. Reefs provide food and beauty to the islands, mainland, and world, attracting tourists and scientists alike.

Using a slate and a pencil to write underwater, Noble marks down a diseased coral: CNAT SCTLD? Translation: Colpophyllia natans, possible stony coral tissue loss disease. Colpophylia natans is the classical ideal of a brain coral, which features winding alleys of polyps separated by peaks and valleys of limestone dressed in vivid greens, yellows, and sometimes, purples—pigments in their resident zooxanthellae that they use to photosynthesize. This coral, however, has been stripped of its regalia, and instead presents swaths of white death.

“Symptoms of SCTLD are highly variable, so it was often difficult to tell whether a colony was affected by SCTLD, another disease, or something else entirely,” says Noble. “Our professors believe that there were cases of SCTLD on the reefs, which was incredibly alarming.”

Though many researchers are trying to find the answer, no one knows what causes the disease. Early studies hint at bacteria, as some researchers have found success in saving some colonies by treating the infections with antibiotics. The first alarm that something was happening to Florida’s reefs was raised by William Precht, an environmental consultant in Florida who has taught coral reef ecology for more than thirty years in the Three Seas program, where he teaches coral reef ecology in partnership with Northeastern associate professor Steve Vollmer. Precht’s research on the cause of the disease is funded by a National Science Foundation grant.

Precht and Vollmer recently attended a meeting in Cozumel, Mexico, once home to some of the healthiest reefs in the Caribbean, now ravaged by stony coral tissue loss disease. In January, Vollmer will be teaching the graduate program of Three Seas, which will continue to monitor the area for new signs of the disease.

“Given the rates of infection and mortality seen in other areas, an outbreak could completely devastate the corals of Bocas,” Noble says. “The reefs that we dove on could be gone a year from now. In a situation like this, it’s really important to hope for the best, but plan for the worst.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.