A new system to help doctors more accurately measure pain may help fight the opioid addiction crisis

Inside a labor room at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, nurses and physicians monitored Yingzi Lin’s vitals, checking on her over the course of three days, and asking how much pain she was feeling. It was 2011, and she was preparing to have her first child.

Lin was hurting. But she struggled to communicate just how bad her pain was to the nurses, who asked her to rate her pain using a zero-to-10 scale that rates more intense pain with higher scores.

“I gave them very low scores,” Lin says. “I was worried that if I gave them high ratings, maybe they would do something I didn’t need.”

Struggling to assess pain based on that scale is not an uncommon issue when doctors treat patients, especially because the concept of how painful something is can vary from person to person. It’s difficult to put a number on pain at the labor room. It’s difficult at an emergency room. And it’s difficult after checking in for, say, a minor ankle sprain.

Lin, a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern, is working on a solution to help doctors and patients gauge pain more effectively.

The Intelligent Human-Machine Systems lab she runs at Northeastern has been studying people’s reactions under stimulus involving small (and harmless) amounts of pain, such as dipping their hand in ice cold water.

“These are physiological responses,” she says. “So you cannot hide them.”

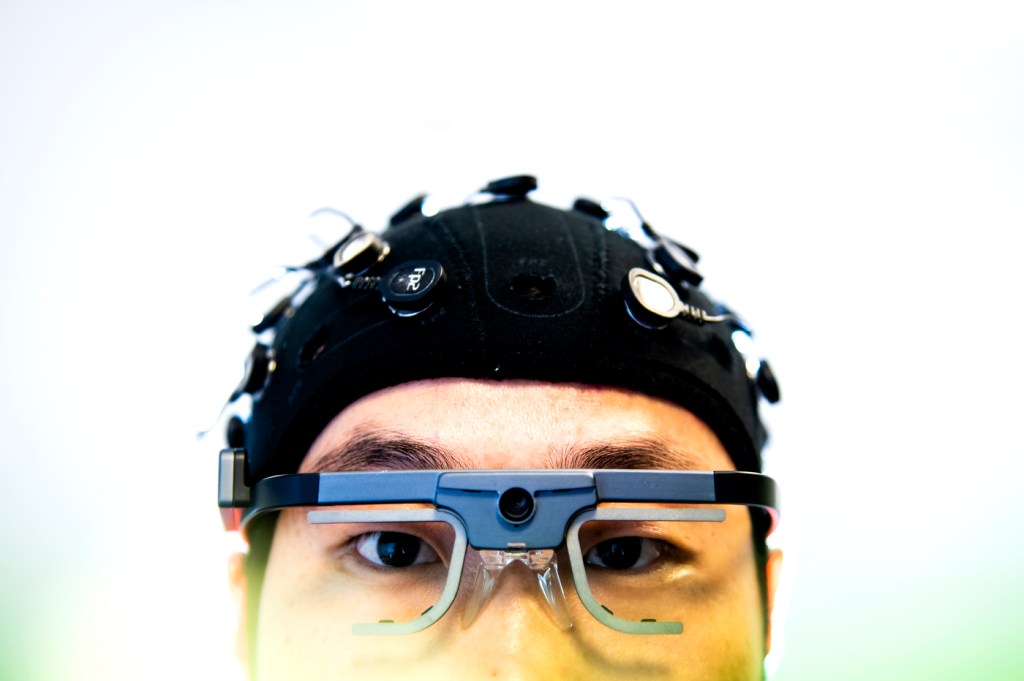

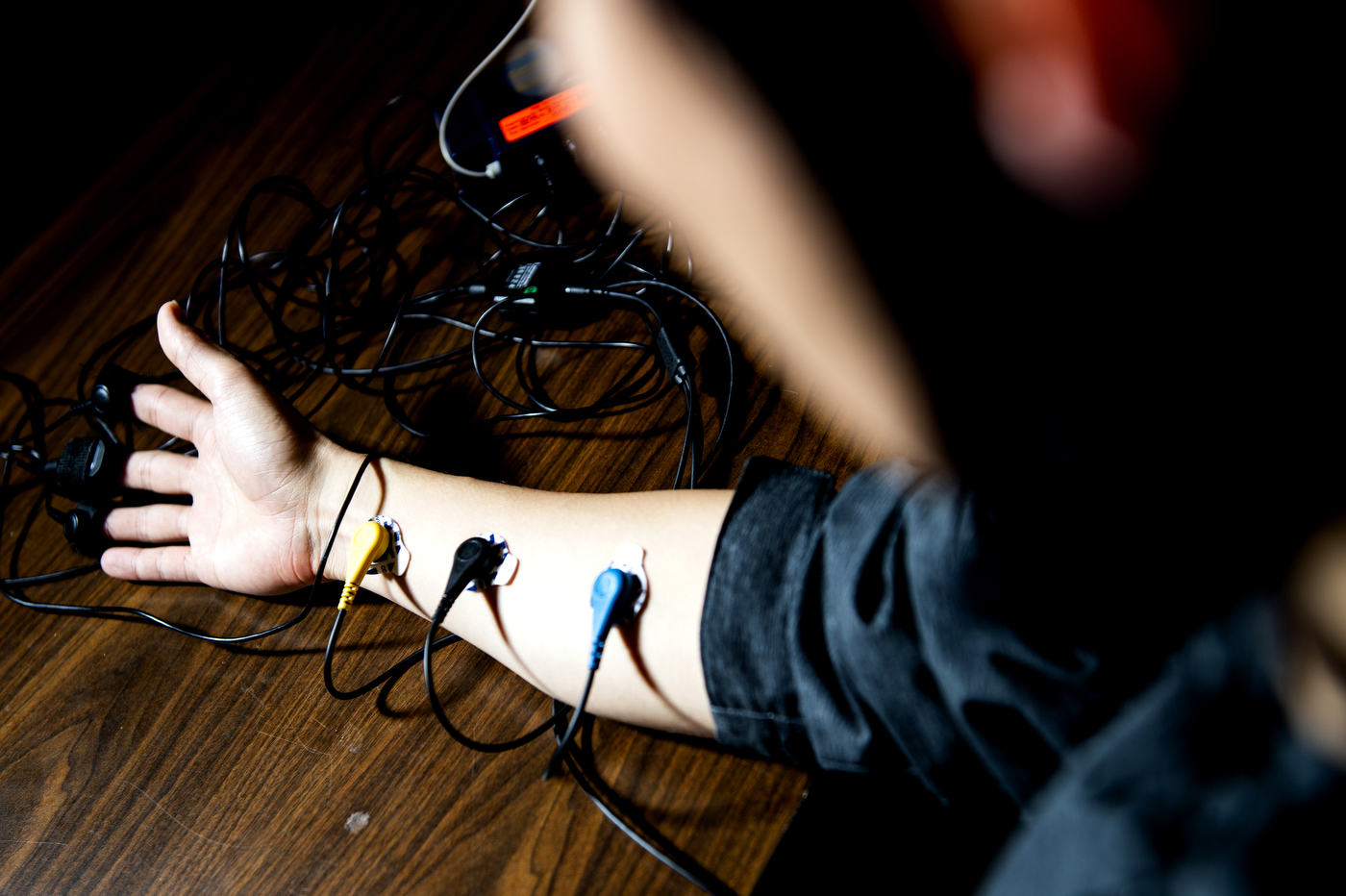

Lin tracks body signals, such as changes in brain activity, sweat glands, pupil dilation, heart rate, and facial expressions—running all those tests as she asks people to rate pain using the zero-to-10 scale.

Her system, the Continuous Objective Multimodal Pain Assessment Sensing System, received a National Science Foundation grant that she is using to conduct pilot studies at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, testing different ways to measure body signals that can help create a system to evaluate pain more accurately. In the next three years, she will also work with Sagar Kamarthi, a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Northeastern, to create a computer program that can hunt for signals of pain in the body.

That kind of system will be a giant leap toward accurately estimating pain levels on the spot, in minutes, and when patients need it, Lin says. And, she says, it’s what doctors need when treating patients who are unable to give their own rating—such as babies born with complications.

“We can’t really tell how much pain they have, so the only indicator doctors have is crying,” Lin says.

Lin is also working with pain management doctors and anesthesiologists, who have to ensure a delicate balance between managing pain and overprescribing painkillers. Her system could be an important weapon in the fight against an opioid overdose crisis that is killing thousands of people every year in the U.S. Because these drugs are highly addictive, and because people might inaccurately assess their pain (even unintentionally), relying on a patient’s self-rating just doesn’t cut it.

“Not because we don’t trust the patients,” Lin says. “But if we have an objective way of measuring their pain, we cannot mess with their doses.”

There isn’t a single body response that can quantify pain for sure, so Lin is tracking as many physiological signals as she can. Since the inception of the project, her lab has been working closely with researchers who specialize in nursing and health technology at the University of Texas at Arlington.

“Doctors monitor all these parameters—we have heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation—and they are very accurate, everything is so advanced,” Lin says. “So why is this pain rating system lagging behind?”

The problem with reporting our own pain is innately human. People’s rankings of pain can be shaped by their sex, age, and different psychological influences. Now targeting that pain, Lin’s system works with technology she has used in her lab to detect people’s emotional states in situations involving machines, such as driving with road rage, fatigue, and drowsiness. As someone who analyzes human behavior for a living, she keeps coming back to a popular quip in her field.

“People are not reliable,” Lin says. “If I applied the same [stimulus] to different people, each one might have a very different experience. Someone could rate it a two, and that could be an eight for someone else.”

But even when estimating pain levels is difficult, it is definitely worth investigating, Lin says.

“It’s very much subjective, but it is a very serious number,” she says.

Lin’s son is now eight years old. Ever since the day he was born, Lin has been thinking hard about how to come up with a better way to estimate pain. Whatever number she would have given nurses in the labor room back in 2011, it was certainly going to be factored into her treatment.

As Lin sits, surrounded by computers, driving simulators, and instruments to test body signals, she thinks of her experience in the hospital. She would probably give doctors a different rating today for the pain she was feeling back then, she says.

“It would probably be more difficult now,” Lin says. “A lot of things are going on in my mind now that I know what’s behind those numbers.”

For media inquiries, please contact Jessica Hair at j.hair@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.