Domestic violence homicides appear be on the rise. A Northeastern University study suggests that guns are the reason.

Since the early 1990s, the number of murders had been steadily dropping. Then in 2015, it jumped up, and it continued escalating in 2016 before falling again. What happened? Were those figures an aberration, or are they a worrisome sign of an upward trend?

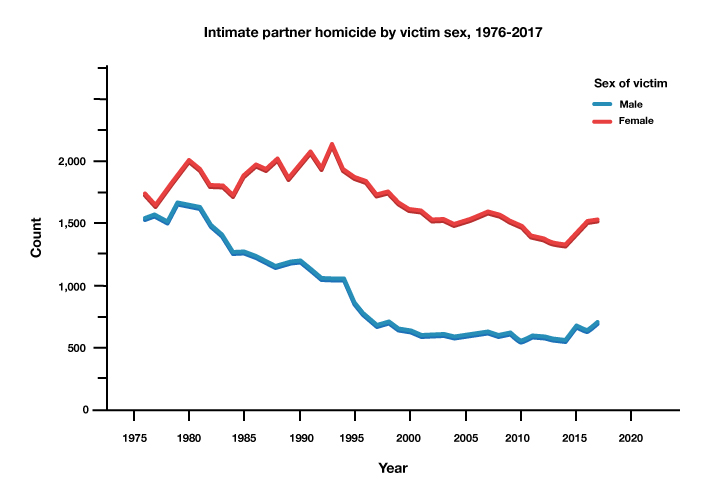

The latest research paper of Northeastern criminologist James Alan Fox draws a number of conclusions about homicide trends, but one of the more salient ones is that between 2015-2017, there was an uptick in homicides among romantic partners that affected both male and female victims.

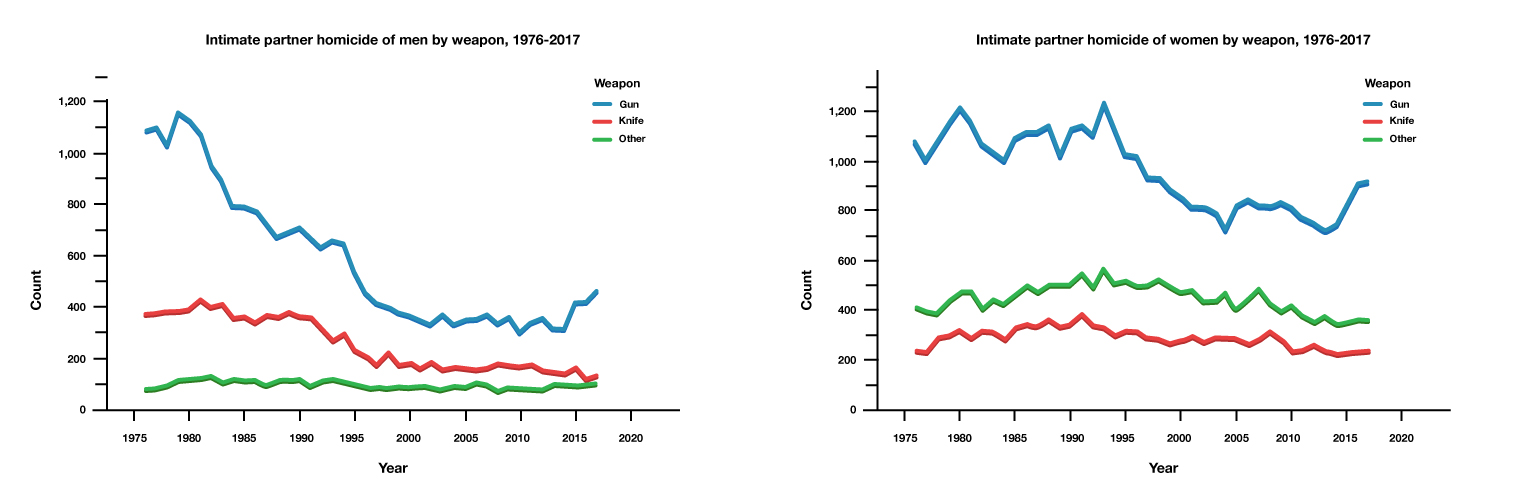

Guns are a big part of this escalation, says Fox, who is the Lipman Family Professor of Criminology, Law, and Public Policy at Northeastern University. He and his co-author, written with Emma Fridel, a PhD student in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, observe that even if purchased for self-defense purposes, all too often a gun in the home is used against a loved one. Sometimes this happens in the heat of an argument, other times deliberately to end a relationship “in a way that is speedier and less expensive than divorce,” as the authors put it.

“We really have to redouble our efforts in terms of preventing intimate partner homicide, especially in terms of guns,” Fox says. “We need to focus more on federal gun legislation. We haven’t had any substantial gun legislation at the federal level in 25 years, ever since the Brady Law.”

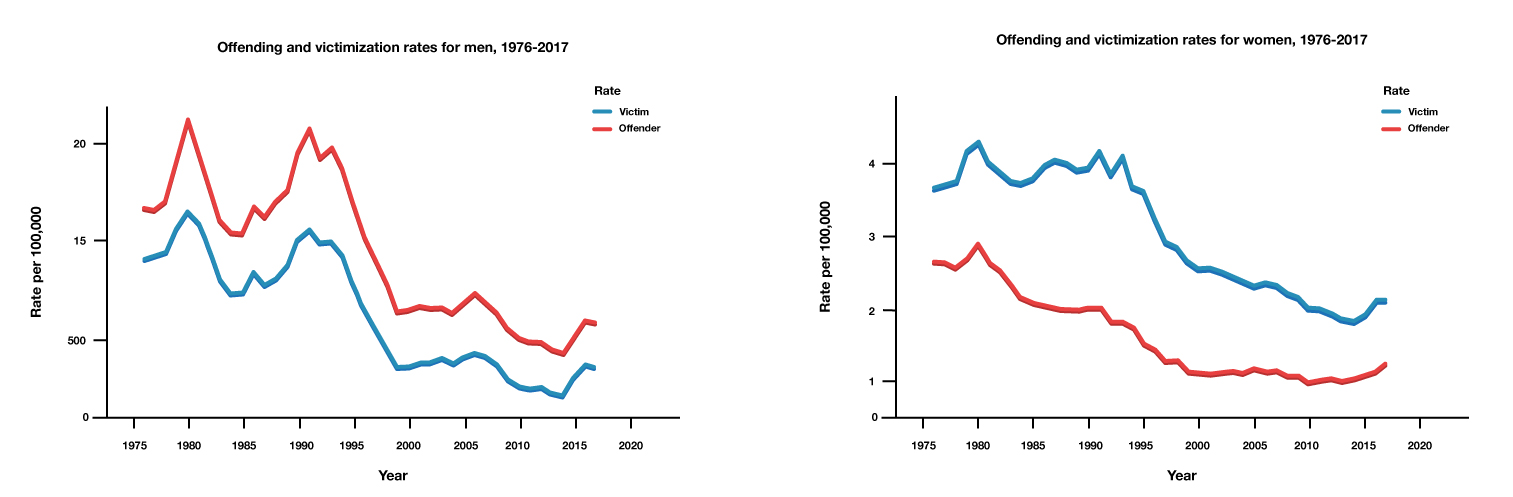

The paper, which was published in March, analyzes homicide patterns and the differences between men and women, as both perpetrators and victims, based on 42 years of data obtained from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The researchers found that the rates of women killing their partners have declined. The authors attribute this to several factors, including the liberalization of divorce laws, reduced stigma associated with being a victim of abuse, restraining orders, and the establishment of shelters for abuse victims.

“The irony is that the beneficiaries were men,” Fox says. “Women didn’t feel as trapped as they once had been in a relationship, where at one point they saw the only way out was to pick up a loaded gun to shoot their loathed husband.”

Fox credits the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which among its provisions included prohibiting the gun rights of people who are convicted of domestic assault, as an effective measure in helping to bring down domestic violence rates. He and Fridel discovered that the incidence of female intimate partner homicide dropped by 56 percent in states with robust gun control policies.

Fox credits the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which among its provisions included prohibiting the gun rights of people who are convicted of domestic assault, as an effective measure in helping to bring down domestic violence rates. He and Fridel discovered that the incidence of female intimate partner homicide dropped by 56 percent in states with robust gun control policies.

Some states have extreme risk protection orders, commonly known as “red flag laws,” which permit police or family members to petition a court to order the temporary removal of firearms from a person who may present a danger to themselves or others. Though these laws have been enacted in the wake of mass shootings, there’s little evidence of their effectiveness on lowering homicide rates, Fox says.

James Alan Fox, the Lipman Family Professor of Criminology, Law, and Public Policy in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities, says homicide among romantic partners may be experiencing an upswing.

Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

“Even though I’m in favor of these red flag laws, there can be a situation where an attempt by a spouse, for example, or a family member to have someone’s guns confiscated can precipitate violence by angering someone who already has a volatile temper,” he says.

The FBI data Fox and Fridel looked at reveal interesting conclusions about how men and women differ in crime. The researchers make the case, for example, that men and women see the utility of violence in different ways: Men use it offensively to establish superiority; women tend to use it as a defense of last resort.

Men who commit murder tend to favor guns, while women prefer using knives, poison, drugs, drowning, and asphyxiation, according to the researchers.

When women kill, they’re more likely to do it later in life (between the ages of 25-34), whereas nearly half of all male killers are younger than 25 years old, the study found.

Women tend to be punished twice, the researchers observe: once for breaking the law and a second time by society.

Men are more likely to be both the perpetrators and victims of homicides, Fox and Fridel found. Women are more likely to be on the receiving end of violence, whereas men are more likely to be the perpetrators than victims of it.

The paper also touches on racial differences. For example, African Americans represent 13 percent of the male population, the researchers found, but they account for more than half of all male homicide victims and perpetrators.

Fox cautions against being too alarmed by the recent rise in lethal domestic violence.

“You get a spike in homicide one or two years, and a lot of people start thinking that the sky is falling. You know, Chicken Little thinking,” he says. “Even though we’ve seen a few years of substantial increase in gun killings among intimate partners, it remains to be seen whether this persists or whether it’s a short-term trend that will self-correct.”

He adds, “I’m hoping that it’s the latter.”

For media inquiries, please contact Mike Woeste at m.woeste@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.