Northeastern University remembers Leonard Brown, celebrated and beloved leader, mentor, colleague, friend, and educator

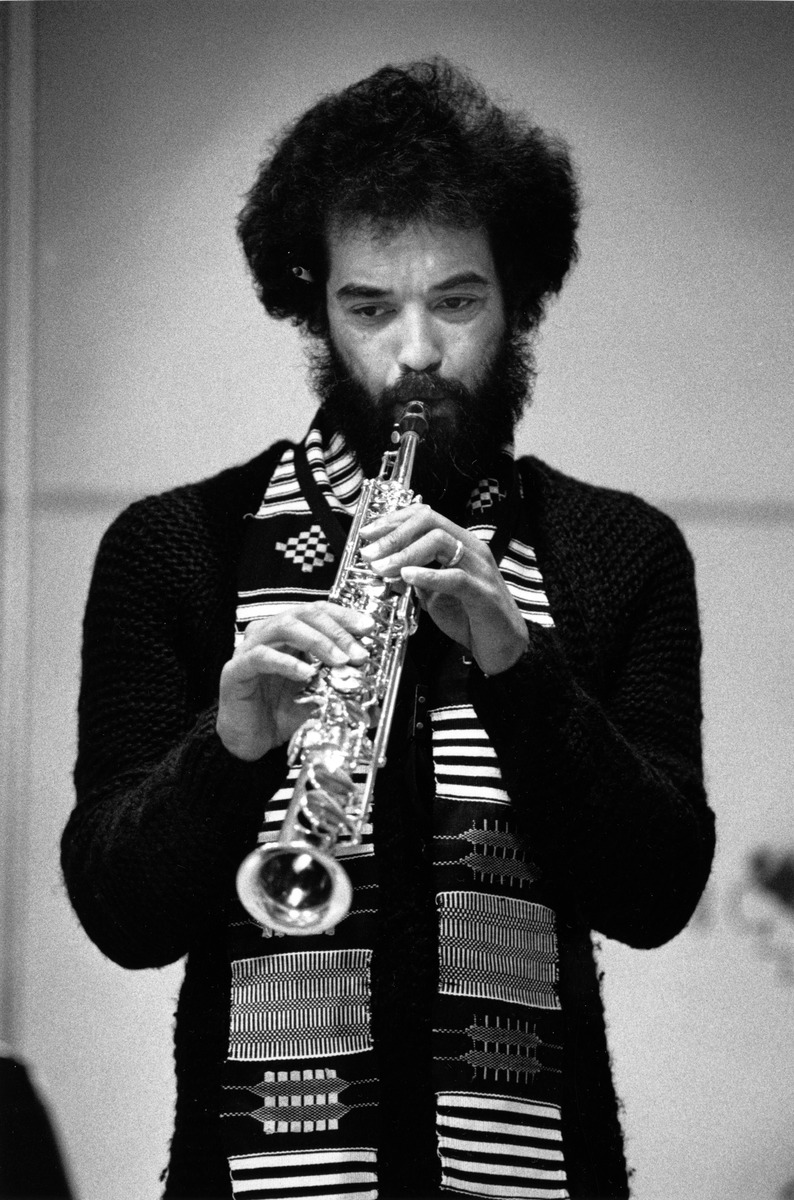

Leonard Lewis Brown was a professional jazz musician—a saxophonist, composer, and arranger— an educator, an ethnomusicologist, and a specialist in multicultural education. Beloved by his students and colleagues and greatly distinguished in his work, Brown passed away peacefully on March 7, surrounded by his family.

Brown was an associate professor emeritus at Northeastern University, with a joint appointment in the departments of music and African American studies.

He enhanced the university as a whole by serving in various positions, including co-director of the Afro-Caribbean Music Research Project, chair of African American Studies department, and head advisor for music. From 2000 to 2003, he served as the university’s vice-provost for academic opportunity. Along with his academic and scholarly initiatives and endeavors, from 1996 to 2002, Brown served as senior ethnomusicologist and principal cultural historian to the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, the first national jazz museum in the nation.

He is remembered as being an advocate for diversity at Northeastern, a supportive mentor to fellow faculty members, and a vibrant, helpful professor to his students.

“Leonard was a man who was tall in stature and tall in integrity; he was brilliant, caring, spiritual, always had a twinkle in his eye, and he cared about his students,” describes music professor emeritus Joshua Jacobson. “One of his favorite expressions was ‘am I making sense?’ He wanted to make sure he was communicating effectively to both his students and colleagues. He certainly influenced many students through his teaching methods, and always made the effort to form a connection with each of his students.”

As an educator in the Department of Music, Brown is remembered for his warm and welcoming attitude, his commitment to collaboration, his magical way of bringing people together, and for always signing his emails with Peace or Love.

Leonard was a man who was tall in stature and tall in integrity; he was brilliant, caring, spiritual, always had a twinkle in his eye, and he cared about his students.

Joshua Jacobson, Professor of Music Emeritus

“Leonard was a stabilizing force in the music department, and he always encouraged discussion and figuring things out. He was fair-minded, and just a great colleague,” describes Leon Janikian, associate professor of music emeritus at Northeastern, who retired in 2018 after serving as a faculty member for almost 30 years. “I felt a strong rapport with him; he understood what I did, and when I became a faculty member as a young assistant professor, he became an informal mentor to me.”

Professor emeritus Leon Janikian, who Brown referred to benevolently as “Dr. Lee,” describes Brown as a “wonderful, wonderful man who would light up a room when he walked into it.” Janikian, a clarinetist, and Brown, a saxophonist, often played music together, an experience that Brown’s energy and creativity made boundlessly fun and interesting.

“He was a spur of the moment person,” Janikian says of Brown. “He was a wonderful musician, a superb saxophonist, and a risk-taker; jazz musicians must be risk takers. He had the mentality that everything would be alright…just keep playing.”

As an ethnomusicologist, Brown’s contributions to the field are unmatched. At Northeastern, he incorporated ethnomusicology into the curriculum and found ways to engage students with the field. He worked with Judith Tick, professor of music emeritus, to introduce new courses and expand on-campus programming.

“He was very fascinated with my work with women’s music history and we found common cause in creating new courses that addressed social issues,” remembers Tick, who joined Northeastern as a music historian in 1986.

An example of one of the new classes Brown spearheaded was “Music as Social Expression,” which allowed him to diversify the course content constantly and offer his students an exploration of a wide range of topics. He also taught “World Music” as part of the core music department curriculum at the time. Regardless of what specific class it was, however, he always challenged students to ask: what is music, where does it come from, and why do we have it?

He fought for those who were just trying to create a place in the world for themselves and create impact.

Ja-Nae Duane, part-time lecturer of entrepreneurship and innovation in the D’Amore-McKim School of Business

“He was a passionate teacher and I always thought of him as someone who embodied philosopher John Dewey’s maxim of showing by doing. He offered his students an experience that was hands-on and varied,” Tick says. “He challenged his students and colleagues to consider new perspectives, and he was very open to different points of view. He was someone who could disagree with you without alienating you.”

Together, Brown and Tick developed a series called Multi-Cultures, Multi-Musics to bring in a variety of speakers outside of the courses they were teaching at Northeastern to further enrich the students and the community. They also collaborated on a production that featured the music of Aaron Copland, American composer, composition teacher, and writer, in 2001.

In his efforts to embed ethnomusicology into Northeastern’s curriculum, Brown also worked to create a position for long-time music department faculty member Susan Asai, associate professor emeritus, in the 1990s. He had heard about the “Music of Asia” course that Asai was teaching at Wheelock College in the early 1990s, and interested in bringing an ethnomusicologist to teach music of this part of the world to Northeastern, Brown collaborated with Holly Carter, who was director of the Asian Studies Program, in creating a teaching position for Asai in the music department.

“He and I worked together to create the ethnomusicology minor degree program and recruit students for a curriculum that we felt would enhance their understanding of musical cultures within contexts that explained music’s role and purpose in people’s lives,” describes Asai. “He and I worked to maintain a curriculum that would provide students opportunities to study and appreciate myriad cultures and forms of music making that would open up their worlds and make them more globally savvy and broaden their resumés.”

This positive mentality brought joy and comfort to those who had the opportunity to know him; he was a loyal friend to his colleagues.

“Leonard was a friend and supportive colleague in the music department; our partnership was enriching for me,” Asai recalls. “I admired him for standing up for his principles and helping me and others keep our ‘Eyes on the Prize’ in supporting equality and dignity for all people. In all that he did, he strove to raise awareness of and advocate for equal opportunities and treatment of faculty, staff, and students of color at the university and beyond.”

His mentorship and support became staples in many new faculty members’ transitions to the university, which continued even after Brown retired.

He challenged his students and colleagues to consider new perspectives, and he was very open to different points of view. He was someone who could disagree with you without alienating you.

Judith Tick, Professor of Music Emeritus

“When I got to Northeastern, Leonard, who had retired a year or two before, was a reassuring presence,” Dan Godfrey, professor and chair of the music department, remembers. “He would turn up from time-to-time in the office, and he helped me get to know the department.”

Godfrey and Brown worked together to create support for the John Coltrane Memorial Concerts, with the music department contributing and encouraging other parts of the University to get involved. “We worked to tie the community and the campus together,” says Godfrey.

Brown was a co-founder of the John Coltrane Memorial Concert, the world’s oldest annual tribute to the extraordinary musician. John Coltrane was a tenor and soprano saxophonist who died in 1967—but whose name and music remain in the upper echelons of jazz. The annual concert is hosted by The Friends of John Coltrane Memorial Concert, Inc., of which Brown was president, in collaboration with Northeastern University. Under his leadership, each year, it promised to be an amazing confluence of students, faculty, and hundreds of people from the community coming together, sitting together, and celebrating. The John Coltrane Memorial Concert was a tradition that Brown held dear to his heart, and he served as organizer as well as performing in the event. It serves as just one example of Brown’s ability to work across disciplines and communities.

This work and service across so many vast areas have left the loss of Brown reverberating through the entire community, both inside and outside of the university.

Richard L. O’Bryant, director of the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute at Northeastern, recalls the support and encouragement Brown was always so willing to share. O’Bryant joined Northeastern in 2003 as a faculty member in political science, and became the director of institute in 2007, an opportunity that Brown encouraged O’Bryant to embrace.

“When I first came to Northeastern, I connected with the folks from the African American studies department, and Leonard was one of the people I had the opportunity to talk to—he knew my dad, like everyone else, but he immediately took an interest in me and my success,” O’Bryant describes. “One of the most important things as a young faculty member is to make sure you do not get isolated; you need people who support you, and Leonard took the time to really help me get connected with people.”

He strove to raise awareness of and advocate for equal opportunities and treatment of faculty, staff, and students of color at the university and beyond.

Susan Asai, Associate Professor Emeritus

As time went on, O’Bryant and the institute also worked with Brown on the Coltrane concerts, contributing to them and helping spread the word to students.

“He would come and talk to students whenever we would ask him to; it was one of the things he enjoyed doing,” O’Bryant explains. “He would always stop to take time to talk to people and ask them how they are doing, from other faculty and staff to the students. He advised students, and encouraged them to diversify their education, and take classes well beyond the departments of music or African American studies.”

Students in the Music Department benefited greatly from Brown’s teachings and advice, especially as he shared his perspectives and enthusiasm in conveying music’s role and significance in cultures, societies, and individual lives.

Ja-Nae Duane, who met Brown when she was a freshman in the music department, is one of these students whose life was touched by Brown. He helped her secure a co-op position working on the John Coltrane concerts, an experience that exposed Duane to jazz and John Coltrane’s impact in the field. He also advocated for Duane as she created her own major (opera).

“It wasn’t until years later, at his dinner table, that I realized how much he actually pushed and advocated for me,” Duane says. “This is why Leonard is going to be missed so much. He fought for those who were just trying to create a place in the world for themselves and create impact. Not everyone creates that impact in the same way, and he knew that. It’s an educator’s place to support students who are trying to synthesize all they are learning and understand how it applies to them and how they move in the workplace.”

One of the most important things as a young faculty member is to make sure you do not get isolated; you need people who support you, and Leonard took the time to really help me get connected with people.

Richard L. O’Bryant, director of the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute

Duane is now an educator at Northeastern University herself, working as a part-time lecturer of entrepreneurship and innovation in the D’Amore-McKim School of Business. Before joining the faculty at D’Amore-McKim, she spent eight years in the Department of Music.

“Now I am a faculty member, but even as a student at Northeastern, it was apparent how much influence Leonard had on the department itself and on the department’s trajectory,” Duane said. “He cultivated ethnomusicology on campus, and as part of that, the synergy he created between the music department and the African American studies department was incredible. It was about building bridges for him, and understanding how all of our roots are all interconnected.”

So many individuals appreciated and enjoyed this type of support, work, and scholarship. Brown’s dedicated service to the Northeastern community and beyond has left a lasting and meaningful impact. A memorial service was held Saturday.