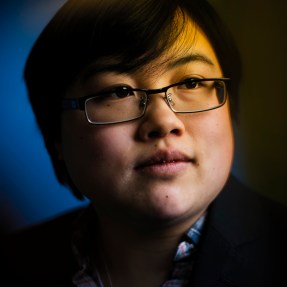

The autistic, non-binary, queer, law student fighting for disability justice

Lydia X. Z. Brown is angry.

A gender non-binary, queer, disabled person of color, Brown is self-described as “multiply-marginalized.” And the third-year law student at Northeastern, whose resumé of activism and pro bono disability justice work spans nearly 20 pages, is angry that there is still a need for this type of effort.

“I’m angry about how I and people like me are treated,” Brown said. “I’m angry at the erasure, the isolation I and people like me have experienced. Ten years after I began doing advocacy work, I’m still saying the same damn things all the time.”

Brown, L’18, is set to graduate in May as a public interest law scholar. Brown identifies as gender non-binary and uses “they/them/their” pronouns, an identification which will be reflected throughout this story.

A visiting lecturer at the Tufts University Experimental College, Brown led a course called “Re-Thinking Disability: From Public Policy to Social Movements.” Among Brown’s accomplishments: Serving as chairperson of the Massachusetts Developmental Disabilities Council; interning on the Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services; participating in the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project and Prisoners’ Rights Clinic at Northeastern; working within the American Civil Liberties Union and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network; and acting as the lead editor of All the Weight of Our Dreams, the first-ever anthology of writings and artwork by autistic people of color.

This year, Brown was named the National Association for Law Placement Pro Bono Publico Award winner. It’s a prestigious honor that acknowledges one law student nationwide for pro bono contributions to society, while recognizing the significant contributions that law students make to underserved populations, the public interest community, and legal education through public service work.

All this barely scratches the surface of Brown’s work.

The thing is, Brown never intended to be a lawyer. A graduate of Georgetown University with a major in Arabic, Brown was inspired by a love of South Asian and Persian Sufi music and poetry.

While Brown had a longstanding “yearning for justice,” they never even intended to become an activist. Indeed, Brown described it as having “fallen into activism by accident.”

Falling into activism

Brown was diagnosed as autistic in eighth grade, and in high school decided to raise funds for an autism awareness walk hosted by a nonprofit advocacy organization. Canvassing the neighborhood, school, and family events, Brown raised more than $1,200 for the group.

While looking into the organization, Brown discovered what they described as behavior that ran opposite the organization’s stated mission of support and advocacy.

Brown decided they could neither keep the money raised nor hand it over to the organization. Brown decided to “get up the guts” to tell the donors what they’d discovered about the organization and return the money.

I believe very strongly—and I have for my entire life, it’s a model that I live by—that each one of us is obligated to use whatever resources we have to fight and challenge oppression in all of its forms.

Lydia X. Z. Brown L’18

Brown took it a step further, though, by reaching out to the people who were posting information online about the advocacy organization, and asking to learn more about the work they were doing.

“That’s how I got involved in disability activism,” Brown said.

It was through these online channels that Brown learned about the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, a national nonprofit disability rights organization whose work includes public policy advocacy and empowering autistic people through self-advocacy. The organization’s motto: “Nothing about us without us.”

‘Ableism ran rampant’

Brown worked with ASAN throughout high school and college, becoming a policy analyst within the organization’s national office in Washington, D.C. by senior year at Georgetown.

Aside from ASAN, however, Brown didn’t expect to be intimately involved in disability rights work. Brown expected to pursue a doctoral degree in Islamic studies as planned. That was not the case.

“It became very apparent to me in my freshman year that there were serious flaws and systemic problems throughout campus. Ableism ran rampant,” Brown said.

“Becoming a student advocate was not a choice, it wasn’t an option, it wasn’t something that I actively deliberated upon and then decided to do; it was mandatory. It wasn’t something that I could refuse to take part in,” Brown said. “I believe very strongly—and I have for my entire life, it’s a model that I live by—that each one of us is obligated to use whatever resources we have to fight and challenge oppression in all of its forms.”

For Brown, that obligation to establish justice included many forms of undergraduate activism. Brown co-founded the Washington Metro Disabled Students Collective; led multiple campaigns to reform policy on disability access that led to the creation of a dedicated funding pool for sign language interpretation, real-time captioning, and a dedicated access coordinator position; organized 11 events related to disability rights; and much, much more.

“As a campus organizer, I did work on so many fronts that it’s dizzying even to contemplate,” Brown said, laughing.

When Brown graduated, their sole position in the Georgetown University Student Association was filled by a team of people.

Challenging oppression in all its forms

By doing disability rights work, Brown slowly became drawn toward disability justice work.

Brown explained that disability rights work seeks equity and inclusion. Disability justice seeks reparations, a deep pivot of values away from ableism, and an understanding that the law alone—in all its plodding deliberateness—may not be enough.

Indeed, Brown sees the manifestation of ableism—discrimination in favor of able-bodied people—everywhere. Sexism is the result of the belief that men and masculinity are the norm and women and femininity are other. Discrimination against queer and transgender people is based on the belief that straight, cis-gendered people are the norm. Racism is based on the belief that whiteness is the norm.

Law is a powerful tool for change.

Lydia X. Z. Brown L’18

“So much of this invokes the larger language of disability,” Brown said, voice rising with passion. “Ableism is everywhere. Disability justice calls on us to fight this, to develop a deliberate consciousness—it is inherently intersectional.”

So, Brown went to law school, continuing a legacy of deeply-engrained disability justice work at Northeastern.

Brown is an active member of the Committee Against Institutional Racism, representing the Asian Pacific American Law Students Association. They are also on the Transgender Justice Task Force and the Faculty Appointments Committee and serve as a founding core collective member of the Disability Justice Caucus.

Jeremy Paul, dean of the School of Law, lauded Brown’s accomplishments at a ceremony this year celebrating their Pro Bono Publico Award. “I’ve learned a lot from you,” he said.

Assistant dean Michelle Harper described Brown as “truly remarkable,” adding that Brown brings “strongly-held values and a critical perspective” to the school’s law scholarship.

“Law is a powerful tool for change,” Brown said. “I could’ve continued my studies as planned, ended up doing academic work that would’ve felt disconnected from doing anything for my community or other marginalized communities. But that path wouldn’t feel right to me.”

And so Brown’s tireless work continues—until, hopefully, it runs out. “I don’t want to have work to do in advocacy, in activism,” Brown said. “That would be great.”