‘A true renaissance man’: Northeastern to honor law professor Michael Meltsner

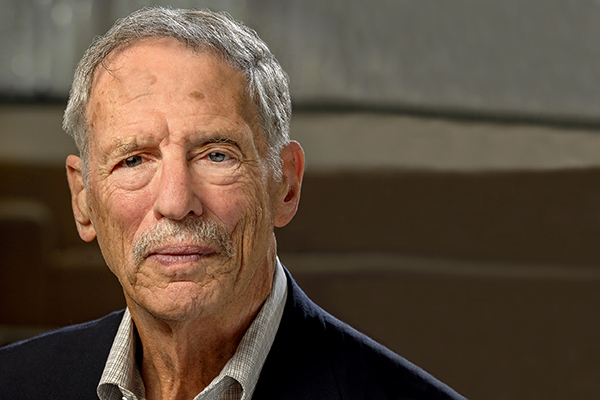

Michael Meltsner, the George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished University Professor of Law, has argued before the U.S. Supreme Court six times and written more than a half dozen books, novels, and plays. The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization focused on the American criminal justice system, said he and fellow lawyer Tony Amsterdam “did more to shape the death penalty law than any attorneys in American history.” And his Northeastern colleagues call him a “true renaissance man” who has “lived an extraordinary life and done extraordinary things.”

In recognition, the School of Law will host a symposium to honor Meltsner’s work on Friday from 8 a.m. to noon in 240 Dockser Hall. The four-hour festschrift will include two panel discussions on Meltsner’s contributions to civil rights and capital punishment law, both of which will feature Northeastern faculty and focus on his work as the first assistant counsel to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in the 1960s.

“I’ll enjoy listening to brilliant and funny speakers,” said Meltsner, a national leader in the fight for civil rights and the abolition of the death penalty, “and I’ll be vividly reminded of how lucky I am to have worked for six decades with so many extraordinary men and women.”

I’m the only living person who was at the Legal Defense Fund when I was hired and I feel a certain responsibility to keep the memories alive.”

Michael Meltsner

George J. and Kathleen Waters Matthews Distinguished University Professor Law

Daniel Medwed, professor of law and criminal justice, organized the symposium. He called Meltsner an “elite scholar,” one of the “unsung heroes” of the civil rights movement, and a good friend who “demands a lot of himself and others.” To illustrate his point that Meltsner keeps high standards, Medwed recalled a personal story from a few years ago. “I once showed Mike a draft of a paper I had written on capital punishment,” he explained. “He tore it apart and told me that I had done better work in the past and that I could do much better with this one. I needed that type of feedback on that particular project, and it provided just the right form of inspiration to spur me to improve it enormously.”

‘A case I could tell my grandchildren about’

Meltsner was born in 1937. He grew up in New York, graduated from Oberlin College in 1957 with a history degree, and received his Juris Doctor from Yale Law School in 1960. “Joe McCarthy sent me to law school,” he explained, referring to the Wisconsin senator who spent almost five years trying in vain to expose communists in the U.S. government. The husband of his favorite high school teacher was a “victim of McCarthyism,” according to Meltsner, and he spent a lot of time watching the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearings. “I saw how lawyers fought against McCarthy and his chief counsel Roy Cohn,” he said, “and that planted the model in my head.”

By the time he was 24, Meltsner was working for Thurgood Marshall as the second white lawyer on the staff of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. It was 1961 and he was a crucial cog in what he described as the “nerve center of the civil rights movement.” As he explained, “we handled more Supreme Court cases in the 1960s than any organization in America except for the Department of Justice.”

His caseload left little time for anything but work. He represented Muhammad Ali in the case that enabled him to return to the boxing ring after refusing induction in the Army; tried the case that led to the racial integration of southern hospitals; and was one of the initiators of the campaign that resulted in a nine-year moratorium on the use of the death penalty.

“I’m the only living person who was at the Legal Defense Fund when I was hired and I feel a certain responsibility to keep the memories alive,” he explained, noting that Robert Kennedy biographer Larry Tye and other well-known writers have interviewed him for their book projects. “Many of the people I worked with are retired or not with us anymore and I’m very fortunate that I still know how to get to work in the morning.”

Meltsner tried his most influential case in 1963: Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital. The case reached the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, where the court held that “separate but equal” racial segregation in publicly funded hospitals was a violation of equal protection under the U.S. Constitution. In addition to leading to the racial integration of hundreds of hospitals in Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia, the verdict spawned the creation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any state or federally-funded program. “It was a vastly influential decision,” Meltsner explained. “It was a case I could tell my grandchildren about.”

A few years later, Meltsner represented Ali in the case that restored his boxing career. The New York Athletic Commission claimed that it had stripped Ali’s right to fight because he had refused induction in the Army. But Meltsner’s research found that the state freely licensed felons, including men who had killed, raped, and robbed. In court, he argued that denying Ali a boxing license violated his 14th Amendment right to equal protection of the law. More than 40 years later, in an interview with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund following Ali’s death in 2016, he explained, “It was clear that the athletic commission sought to punish him because he was an outspoken black man and a member of the Nation of Islam.”

‘If you listened carefully, you could hear typewriters over the cars’

Meltsner recalled the Ali case in his 2006 memoir The Making of a Civil Rights Lawyer. He’s also written a novel—1979’s Short Takes, which follows a New York lawyer named Jeremy whom The Boston Globe called “funny, caring, searching, and all-too-humanly paradoxical”—and a play called In Our Name, which has been praised as a “living essay in which the United States’ actions at Guantanamo Bay are put on trial.”

“If torture is not wrong in both the legal and moral sense,” Meltsner said in 2012, before the play was performed in Boston and New York to great acclaim, “then it’s hard to imagine what is.”

Writing has long been a part of his life. “In a sense I’ve always felt a bit miscast as a lawyer, so I paid attention to stories,” he explained, noting this his new book, With Passion: An Activist Lawyers Life, is due out later this month. “I grew up in a writing, publishing area of New York City where you could hear the typewriters over the cars.” As it turned out, Meltsner had the opportunity to write Short Takes in the New York City apartment belonging to literary figure Joseph Fox, a prominent editor who spent more than 35 years fine-tuning the work of star novelists like Truman Capote, Philip Roth, and Ralph Ellison.

On Day 1, Meltsner noticed a tall stack of papers in the corner of Fox’s kitchen table. He picked up the paper topping the stack and discovered that it was the first page of John Irving’s manuscript for his 1978 book The World According to Garp. “I got through the first page and realized that if I read the second page, everything I wrote would be totally infected by it and I would be in trouble,” he recalled, noting that Fox ended up buying and editing his book. “For months and months, I wrote my novel looking at the pile of papers.”

Perhaps his most well known book is 1973’s Cruel and Unusual: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment. The book, which death penalty scholar Evan Mandery recently called “the best and most important” work on capital punishment, chronicles in painstaking detail the Legal Defense Fund’s nine-year struggle to abolish the death penalty in the United States. It culminates in the 1972 case of Furman v. Georgia, in which the Supreme Court held that the death penalty constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and 14th Amendments.

“We tried to show that the death penalty was not a necessary aspect of the American criminal system and had enormous defects,” Meltsner explained. “While this was an up-and-down process, we stopped all executions from 1967 to 1976.”

‘Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you’

After working for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund from 1961 to 1970, Meltsner returned to the world of academia. As a professor at Columbia Law School, he co-founded the school’s first poverty law clinic, a program that trained law students by enabling them to work with clients and in the courts. After nine years at Columbia, he became the dean of Northeastern’s School of Law, a position he held from 1979 to 1984. Aside from a five-year stint as a visiting professor and director of the First-Year Lawyering Program at Harvard Law School from 2000 to 2004, he’s remained at Northeastern ever since.

I grew up in a writing, publishing area of New York City where you could hear the typewriters over the cars.

Michael Meltsner

He praised the law school’s long-held commitment to experiential learning and public interest law. “The school has remained faithful to its initial purposes, which were to learn by doing and engage in progressive lawyering,” he explained, “and those two things are extraordinarily seductive to me.”

Next quarter, he’ll be teaching two courses: “First Amendment” and “Constitutional Litigation.” And he couldn’t be happier to be returning to the classroom. “As a group, Northeastern law school students are socially concerned,” Meltsner said. “They want to learn on the ground, they want to get involved, and they’re very diverse.”

Meltsner is fond of quoting 20th-century poet Phyllis McGinley when asked to dole out nuggets of hard-earned wisdom to aspiring lawyers. “Tell a tale but seldom twice,” McGinley wrote in “A Garland of Precepts.” “Give a stone before advice.” But he’s often lived his life according to a pithy saying by Satchel Paige, one of the greatest professional baseball players of all time: “Don’t look back. Something might be gaining on you.”

“When you’re a civil rights lawyer, they’ll be some wins and some losses—indeed, probably more losses than wins,” he explained. “So you need to keep going with stamina and persistence.”