Professor seeks ‘flashes of insight’ in regeneration research, innovative optics

Samuel Chung is motivated by the “flash of insight”—that moment when days upon days of research result in a key breakthrough or discovery. He’s already encountered a handful of these moments in his career—whether it be pioneering a laser surgery technique in worms or building a prototype of a microscopy tool for his research as a cheaper alternative to commercial options—and he’s hoping for many more at Northeastern.

“I live for that. I enjoy it a lot,” said Chung, a newly appointed assistant professor of bioengineering. “Getting there is the challenge. The day-to-day work is not as exciting, but when you get to the moment of discovery, it’s really amazing.”

Chung, who joined Northeastern’s faculty this fall, said he is excited to help grow the College of Engineering’s Department of Bioengineering. His lab, located in the university’s new Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex, will focus on two research tracks: neuroregeneration and optics. Prior to Northeastern, Chung worked as a postdoctoral fellow at Boston University’s School of Medicine, where he laid substantial groundwork for the research he’ll continue in ISEC.

The long-term goal of my research is to look for ways to stimulate central nervous system regeneration in people with spinal cord injuries.

Samuel Chung

Assistant professor of bioengineering

Chung studies nerve regeneration, specifically in a type of roundworm called Caenorhabditis elegans. He said a major benefit of studying these worms—which are only about a millimeter long and as thick as a strand of human hair—is that they are transparent, allowing researchers to see each of their 302 brain cells under a microscope. Using laser surgery, Chung’s research has revealed new insights into the regeneration of brain cell fibers called axons..

In a seminal paper published last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Chung and his colleagues described their observation of “lesion conditioning” in the worm. Lesion conditioning in mammals has long been known to trigger central nervous system regeneration. The next step of his research is to identify which genes in a worm’s nerve cells are involved in lesion conditioning. This is an important step, he said, because once you find the genetic pathway, you can then begin to explore ways to stimulate regeneration.

“The long-term goal of my research,” Chung said, “is to look for ways to stimulate central nervous system regeneration in people with spinal cord injuries.”

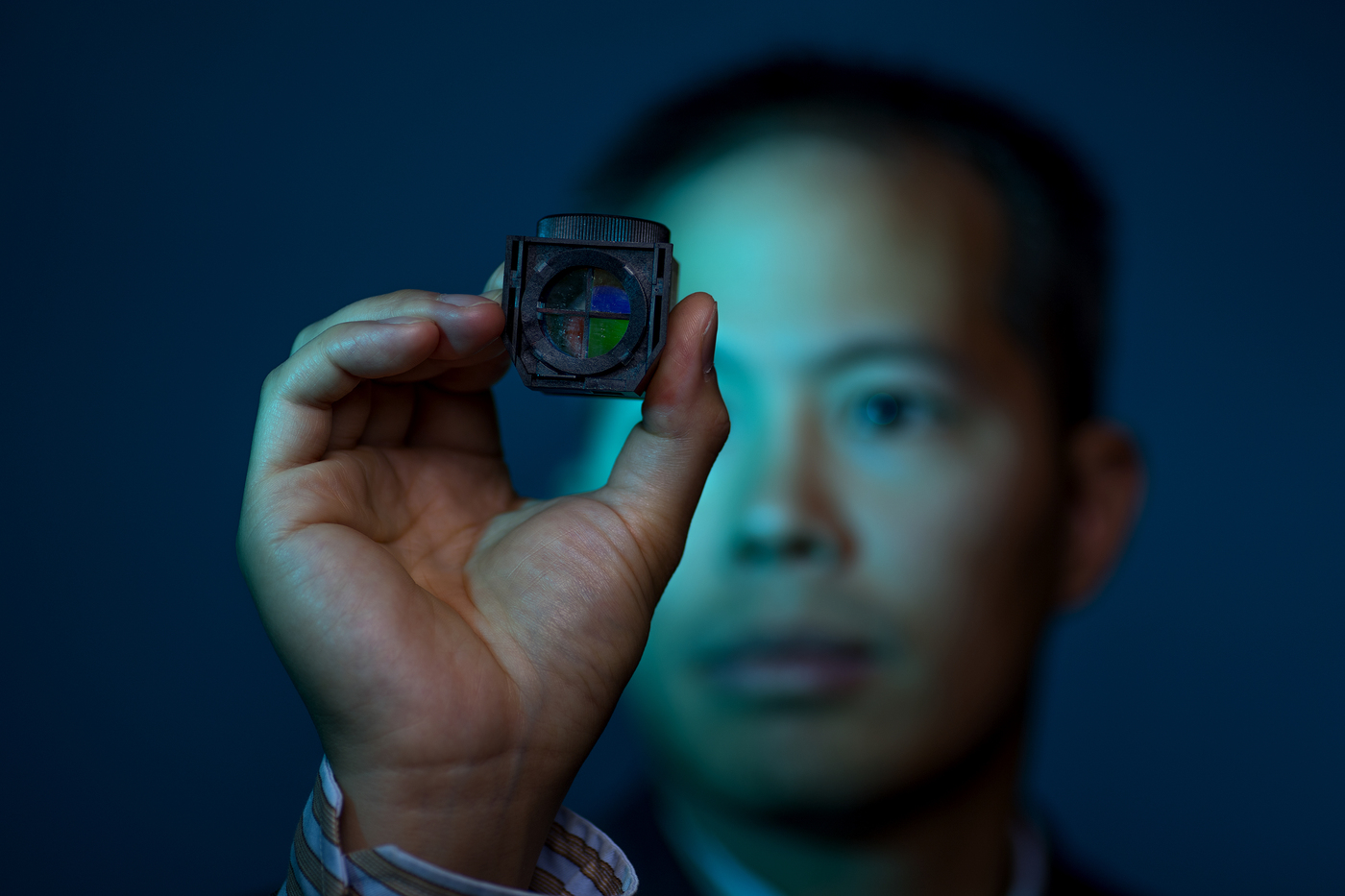

Chung’s other research area of focus is more entrepreneurial. He and his postdoctoral advisor at BU, Christopher Gabel, developed a custom optical instrument that slides easily into a microscope and allows researchers to observe neuronal activity through multiple color channels. The value of viewing multiple color channels side-by-side, Chung explained, is that, for example, he could tag two cells with different fluorescent dyes and then observe their responses simultaneously.

Despite the ubiquity of multichannel imaging and the presence of commercial options that offer this function, Chung said these commercial setups are quite large—and expensive. His prototype, on the other hand, is about the size of a quarter, and is robust, user-friendly, and cheap. He estimated that his version could sell for about one-third the price of a commercial setup.

Chung is now working to develop a second-generation version of the optical device. But he doesn’t envision this venture turning the optical market on its head or competing with labs heavily invested in this area. Rather, he’s interested in creating a “quick and dirty” alternative for biologists and other researchers who lack the expertise in setting up optical equipment.

“They want a simple, easy-to-use device that you can throw into a microscope and know it’s going to work,” he said.