Art’s place in the science world

This is a guest blog post from Madlen Gubernick, SSH’17, an international affairs major with a double minor in journalism and photography.

As a non-science student at Northeastern, terms such as tissue engineering and biocompatible scaffold used to mean nothing to me. When I was approached by the College of Arts, Media and Design to attend a luncheon in November in which these terms would be discussed, I was a bit perplexed. You want me, a journalism and international affairs student, to cover a science meeting? Despite my initial hesitation, the opportunity provided me great insight into the world of tissue engineering and biocompatible scaffolds, two terms that now make a lot more sense to me.

This event also introduced me to the research of Carol Livermore, an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering.

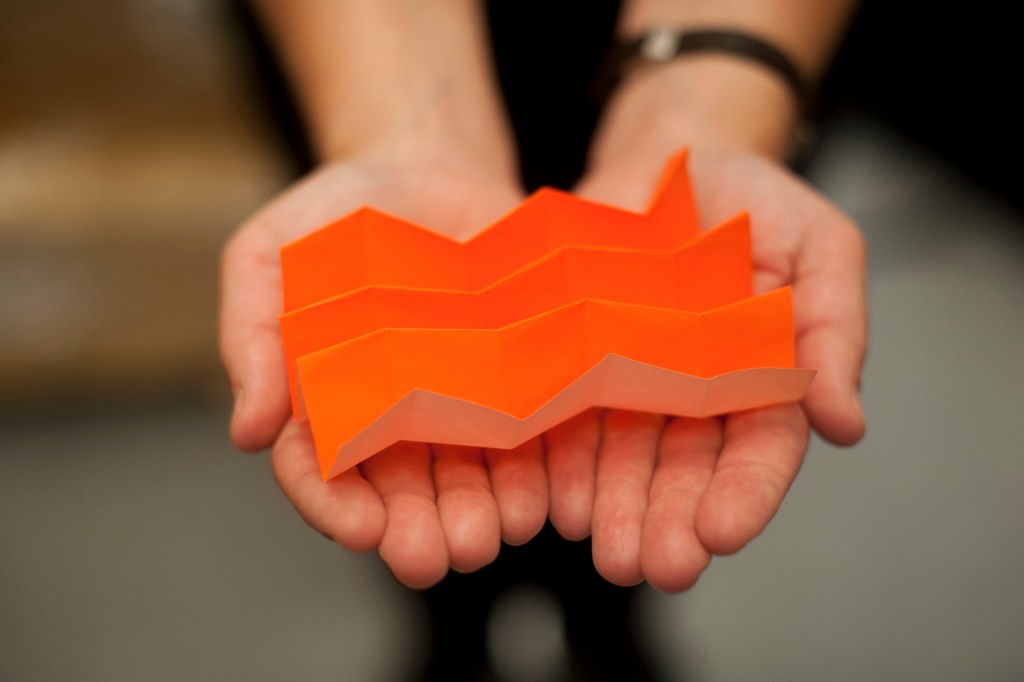

The luncheon included world-renowned origami artist Paul Jackson, industrial designer Theio Brunner, and Northeastern faculty and staff. Livermore discussed the role of art in the science world—more specifically, the importance of origami in scientific research. For those art, business, math, and computer students out there, scientists are using the ancient Japanese art of paper folding to mimic folds of organ and liver tissue, applying a variety of pressures to the origami and then noting the paper’s reaction. Livermore is doing this work right here on campus, alongside Northeastern students.

After the luncheon, I remained fascinated by Livermore’s research, so I followed up with her to learn more. We discussed how exactly she got involved with origami research. “This is my first foray into bringing art into my research,” said Livermore, whose expertise is in microsystems.

“If you need an organ transplant, you usually have to wait for a suitable donor to die,” she said, “Wouldn’t it be better if you could have a replacement organ, or tissue, grown to order from your own cells?” Livermore and her students are working toward this goal with the support of grant funding from the National Science Foundation and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Prior to working with origami, Livermore considered creating tissues as if they were poster paper. “My first idea was to roll up a two-dimensional, cell-patterned sheet, like a cinnamon roll,” Livermore said. “The problem with that is familiar to anybody who’s ever rolled a poster. If the rolling angle isn’t perfect, it comes out wrong.”

During this state of frustration, Livermore saw that the NSF had requested the use of origami in scientific research and then had a thought: “It occurred to me that origami was a better solution than rolling,” she said.

Livermore has thus far discovered a lot through her research by demonstrating basic organization of cells as well as the development of the first self-actuating folds. Her team has also used origami to demonstrate folds that replicate flow patters of liver tissue. Science students or not, we can all celebrate the introduction of art into the science world.