Intelligence, religion, and the twisted-up mind-game that is statistics

Potentially surprising fact: there’s a positive correlation between ice cream consumption and drowning deaths, as one goes up, so does the other. At first glance this sounds pretty horrifying, but, as my stats-teacher-husband loves to remind me, they have nothing to do with each other directly. Instead, their correlation is governed by a third “confounding variable,” which is the weather. As it gets hotter, more people eat ice cream. Likewise, the heat causes more people to go swimming, thereby increasing the likelihood of a drowning death.

Since I was a kid, my dad has enjoyed reminding me that “correlation does not mean causation.” The ice cream-drowning story was the first to drive the notion home for me.

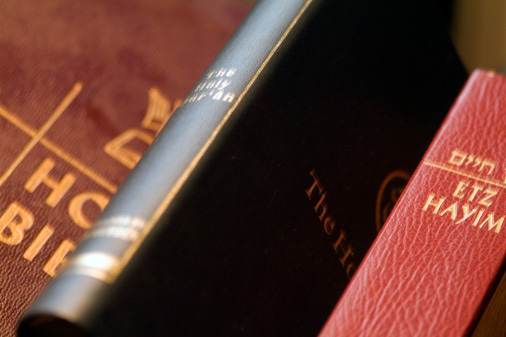

A new paper from Northeastern psychology professor Judith Hall and her colleagues at the University of Rochester brought the idea to mind once again. The paper, “The relation between intelligence and religiosity: A meta-analysis and some proposed explanations,” reports the team’s analysis of 63 separate studies carried out over the last century, and confirms a long-examined hunch that more intelligent people tend to be less religious.

I’d been puzzling over how to write about the article for a while, when I found myself eating sushi with that stats teacher I mentioned earlier. This is the sort of subject that is bound to get people’s knickers into twists so I wanted to be careful. I kept returning to the same phrase: “The studies they reviewed show that intelligent people tend to be less religious,” I kept telling the teacher-husband. I couldn’t disentangle that truth from the question of causation. It sounded so much like they were inextricably linked. Then the husband-teacher asked me a couple important questions: “Does being intelligent cause people to be less religious?….Does being religious cause people to be less intelligent?”

The answer to those questions seemed unlikely, to me, but very difficult to prove with any amount of certainty. If you wanted to prove that religion causes lower intelligence, or vice versa, you’d have to do some kind of double-blind, randomized trial, conferring intelligence on some people and looking at whether they became more or less religious, or vice versa. Despite the obvious challenges with this setup, I’m sure no institutional review board would ever go for it.

This all then brought to mind a phenomenal story I heard on NPR the day before on the TED Radio Hour. Margaret Heffernan, a British writer and businesswoman, told the story of a researcher named Alice Stewart, who, in the 1950s, wanted to figure out why the rate of childhood cancer was increasing, particularly among affluent families. Not knowing at all where to begin, she sent a ginormous questionnaire to parents of children with and without cancer. She asked them every question she could possibly think of. One of these, was a question to mothers: did they have an obstetric x-ray while pregnant? It turned out there was a serious statistical correlation between answering “yes” to this question and having a child with cancer.

At this point, Stewart’s data was akin to what Hall and her team have got now: Responses from people of varying levels of intelligence about their religious beliefs and practices. But lucky for Stewart, she would have an easier (if not at all easy…it took another quarter century before clinics would stop giving pregnant women x-rays) go at proving a causation behind the correlation she’d observed.

With the intelligence and religion question, things are less straightforward. “The present findings are correlational and cannot support any causal relation,” Hall and her colleagues write in the article. But they do present a few hypotheses as to what might explain the statistically significant correlation they and their predecessors observe. In one scenario, they note that intelligent people, who also tend to sway towards nonconformity, may be less religious because religiosity is a societal norm that they are trying to steer away from. Another possibility, they suggest, is that the cognitive style of people with high IQs is typically analytical. And when it comes to spiritual beliefs, there’s simply no way to empirically test the questions at hand.

Finally, the authors suggest that something called “functional equivalence” makes religion fundamentally unnecessary to people with higher IQs: Other studies have shown (through statistics of course) that religion helps people make sense of the world around them, offering a sense of order and external control. It helps us feel better about ourselves and others, helps us delay gratification, lowers our sense of loneliness, confers safety and security in times of distress….Other studies have shown all of these things to be true of high IQ as well. So, the authors suggest that perhaps where religion serves a particular purpose for some people, intelligence does the same for others.

I should also mention that the meta-analysis mostly looked at studies of Christian religions in western societies….because that’s were most of research has been done in the field so far. Looking at other cultures and religions could obviously open a whole bunch of doors for more explanations and hypotheses.

So, what does all of this tell us? Basically, don’t jump to conclusions: