More superbugs than one

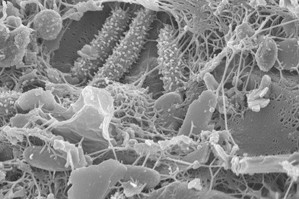

A natural community of bacteria growing on a single grain of sand. Photo by Northeastern post doctoral research associate, Anthony D’Onofrio.

Last week I went to an interesting event hosted by Northeastern’s College of Engineering that opened my eyes a little wider to the problem of biofilms. These are colonies of bacterial cells that stick to all kinds of surfaces–from the bones in your spinal cord to paper towels in a trash can. It wasn’t until the last few decades that biofilms even came to the attention of scientists and while they’re responsible for the most intractable infections out there (think MRSA), doctors have been slow to adapt to a biofilm approach to infectious disease.

The National Institutes of Health attributes 80 percent of all human infections to biofilms, which, because of their unequaled ability to persevere under harsh conditions, are up to 1000 times more resistant to antibiotics than individual bacterial cells that float freely through the environment. With $2.5 trillion spent on chronic infections each year, it seems like biofilms would be an important area of research for the United States healthcare industry.

Nonetheless, virtually all of the antibiotics, disinfectants, and diagnostic techniques used regularly by clinicians were developed through research into the “planktonic,” or free-floating, form of bacteria. This is problematic because that which doesn’t kill a bacterium only makes it stronger. In the decades since antibiotics have been successfully treating our most virulent microbial foes, their less-popular brothers have been sliding by unscathed and are evolving to become even more difficult to treat.

Last week’s event, Biofilm Innovations 2013, was hosted by Northeastern professor and chemical engineering chair Tom Webster and Richard Longland, founder of the Arthroplasty Patient Foundation and director of the recently released documentary, Why Am I Still Sick? Following a poster presentation of biofilm treatment and prevention research taking place at Northeastern, guests participated in an interactive, multimedia lecture series with presentations from leading scientists in the field.

Webster presented the work he’s doing with nanotechnology to develop antimicrobial materials. He’s done similar work in tissue engineering, where the paradigm is mostly well understood by now. They can predict exactly how mammalian cell types will grow on surfaces decorated with nano-particles based on the energy of that surface. But the same cannot be said for bacterial cells. While he has developed surfaces with nano-features that do prevent microbial growth, much remains to be done to fully understand the phenomenon and thus tune it for particular needs.

Garth Ehrlich of the Center for Genomic Sciences in Pittsburg argued pretty convincingly that taking a genetics approach to diagnosing chronic disease is the first step in a successful treatment paradigm. “If you rely on the cultural techniques we were taught” said Ehrlich, “you will find that a majority of biofilm infections will come up negative.” As a result, many chronic illnesses were not thought to be infectious. “It held back our understanding of chronic infections for a very long period of time,” said Ehrlich, whose method of rapidly screening for bacterial DNA is able to identify dozens of bacteria in infections that turned up negative with traditional methods or only presented the most common bacteria, like staphylococcus.

Earlier I mentioned MRSA, or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It’s gotten a lot of attention lately, which is good. But staph infections are just the tip of the iceberg, said Randy Wolcott, a medical doctor from Lubbock, Texas who specializes in treating “unhealable” wounds. Wolcott uses genetic diagnostics to identify the bacteria in some of the most remarkable wound infections you never want to see. The horrifying staph infections most of us have heard about by now are peppered with a slew of other bacteria, and until all of them are addressed, the infection will persevere to the point where amputation can become necessary. He also argued the importance of topical antibiotics, noting that taking a pill dilutes the active ingredient throughout the body, so that what shows up at the site of infection is not strong enough to do meaningful damage.

Using the DNA approach, Ehrlich also demonstrated that oral bacteria show up in infections at the knee joint, something that could have never been seen otherwise and put an important spin on the research of the next presenter. Daniel Sindelar is the president of the American Association for Oral Systemic Health. “The mouth is the gatekeeper for the outside world,” he said, noting that gum disease is a biofilm disease that can spread to the rest of the body. Eighty-five percent of Americans have some form of periodontal disease, he told the audience, but only five percent of us get treatment for it. “How did the mouth get separated from the body?” Ehrlich asked. “It’s the primary portal of bad bacteria.” He presented a few case studies to demonstrate just how serious he was.

Here’s one: a 55 year-old healthy, non-smoking male of normal weight and cholesterol developed significantly increased levels of two enzymes that are highly correlated with heart attack and stroke. This man’s risk of developing a heart attack in the next eight years was 80-90 percent. After doing nothing but stepping up his oral-care in some pretty significant ways, the man’s LP-LPA2 levels reduced to normal and his risk for heart attack dropped by 80 percent.

I’ve been religiously flossing and rinsing with Listerine ever since.

A lot of mysteries remain about biofilms, but the conference drove home the point — at least for me — that the few things we do know about these nasty infections warrant significant attention from the public health and scientific communities alike.