Corporate pay gap = slacking off? Not so fast

Over the last several decades, the pay gap between CEOs and rank-and-file employees has increased at an unprecedented pace. According to the AFL-CIO, the average U.S. CEO earned 352 times the pay of the typical American worker in 2012, up from 42 times in 1980.

The CEO-to-worker pay imbalance has drawn the attention of the popular press, while the Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed that public companies disclose the earning disparity between their employees and chief executives.

But a recent study by two Northeastern University researchers suggests that the pay differential between CEOs and regular workers does not negatively affect the bottom line, stifling neither employee productivity nor firm performance. Instead, the pay gap appears to motivate employees to work harder, especially at smaller companies in which promotions are performance-based. At firms with fewer than 3,250 employees, the study found, the motivation to move up the corporate ladder led to a production increase of 10.5 percent.

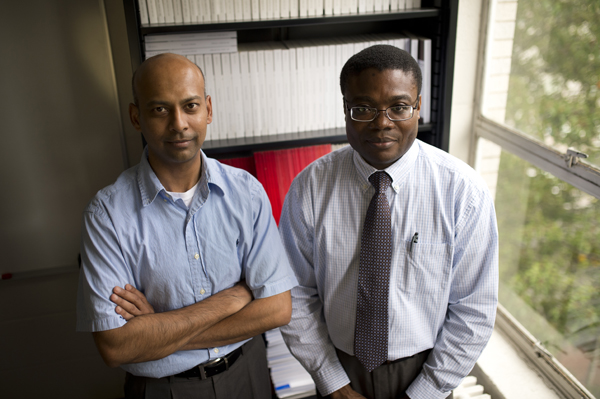

“Employees at firms where promotion is dependent on merit see an opportunity to close the pay gap by upping their effort,” explained coauthor Olubunmi Faleye, an associate professor of finance and insurance and the Trahan Family Faculty Fellow in the D’Amore-McKim School of Business.

The results of the study were published in the August edition of the Journal of Banking and Finance. In addition to Faleye, the study’s authors comprised Anand Venkateswaran, an associate professor of finance and the Edward Philip Chase Fellow in DMSB; and Ebru Reis, an assistant professor of finance in the McCallum Graduate School of Business at Bentley University.

Their findings were based on executive compensation data for firms in Standard and Poor’s 1500 indexes from 1993-2006. The average CEO in the sample earned $4.6 million per year while the average worker earned $59,870.

The authors measured firm performance by calculating revenue per employee as well as total-factor productivity, which assesses a firm’s output relative to the size of its inputs.

Using these metrics, they analyzed a series of special cases in which the pay gap could be expected to transform hard workers into slackers. In one case, the researchers looked at unionized firms in which employees faced a low risk of managerial retribution for shirking their responsibilities. In another, they looked at firms in which employees were more cognizant of the compensation of their top executives because of their presence in the mainstream press. In each instance, the researchers found no correlation between pay ratios and job performance.

“But this does not mean that employees do not care about pay,” noted Faleye. “You would care if I made $50,000 and you made $30,000 for the same job.”

In conclusion, the authors stopped short of recommending a corporate compensation structure and dismissed the idea of legislation to limit CEO-employee pay ratios.

“We believe such propositions are well-intentioned, yet our findings suggest that they are likely to impose unintended costs on some classes of firms while not benefitting others,” they wrote. “We hope that these results will stimulate additional research into these issues with a view to providing comprehensive evidence that informs sound public policy.”