This researcher faced pushback, but her work in criminology could not be derailed

New research from Northeastern looks at Joan McCord’s legacy through her correspondence and how she helped the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study.

There’s been much published about the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study, which looked at the impact of intervention on delinquency in young Massachusetts boys. The groundbreaking research followed up with study participants for decades after the fact and found that the interventions they received as youths did not help them later in life.

But until now, not many have cast an investigative eye on Joan McCord, the noted criminologist who directed CSYS from 1975 to 2004.

Brandon Welsh, dean’s professor of criminology at Northeastern University, and criminology Ph.D. candidate Heather Paterson recentlypublished an article in The British Journal of Criminology that examines archival material to consider whether the initial blowback to the results had a lasting effect and whether McCord’s identity as a woman affected the initial controversy. While the research couldn’t completely determine how McCord’s identity affected the response to her work, they found she did experience some prejudice, none of which derailed her work.

“For this particular research, we wanted to take a historical lens on a particular point in time of the study (and) a rather consequential point,” Welsh said.

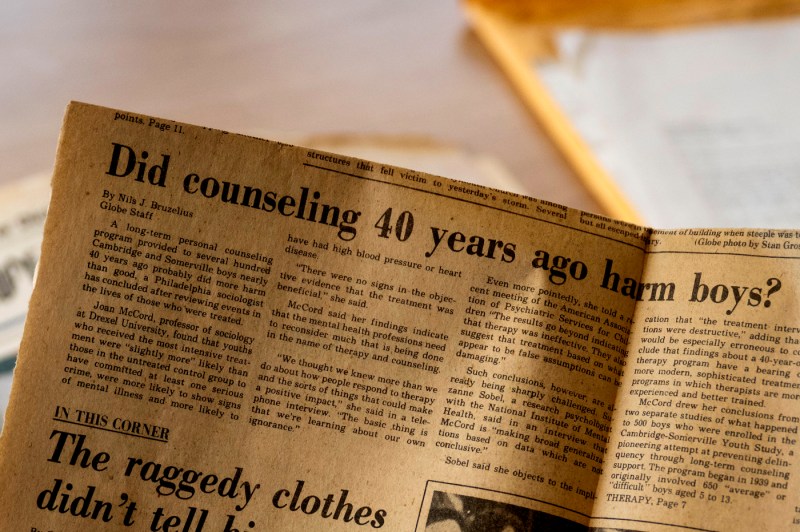

Their paper focuses on McCord’s early years as director of the study. In 1975, she conducted a midlife follow-up of the study when the men involved were, on average, in their mid-40s. Her research found that many of the men in the intervention program fared worse than their counterparts in the control group. They were more likely to have committed more than one crime, died before 35, find work unsatisfactory, or suffer from stress-related disorders, alcoholism or mental illness.

These particular findings, Welsh said, have been foundational in the field of criminology, thanks in no small part to McCord’s work. But they were not positively received at the time, in part because they contradicted the expected outcome. However, the researchers wondered whether McCord’s identity as a woman could have also played a role.

“For her to remain dedicated to the work by being transparent and receiving a lot of blowback is something we wanted to document for history’s sake,” Paterson said. “She received some negative reactions from the public and academic community. That led us to ask this question about if and how Joan McCord’s identity as a woman impacted some of the way the results were received by the public and academic communities. It’s still relevant to today’s world as far as the treatment of women in academia relative to their male counterparts.”

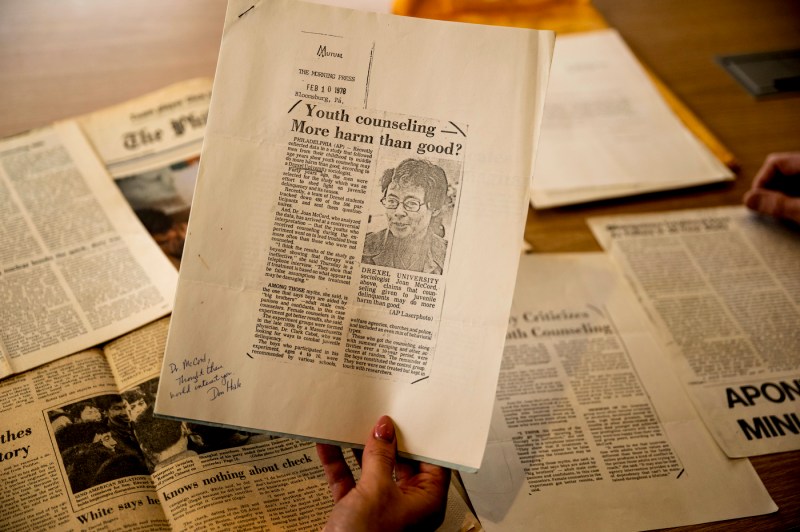

Welsh is the current director of CSYS, having taken over the study in 2015, and Paterson joined the research team about five years ago. Welsh is also the keeper of McCord’s archives, which the two relied on to do research not only about the legacy of McCord’s findings, but her own experience when reporting them. In her papers, they found newspaper clippings about the study, unpublished conference papers and extensive correspondence.

“There was a whole variety of different sources, which made it really interesting,” Paterson said. “It’s like a puzzle, putting together the different pieces.”

Combing through dozens of boxes of McCord’s papers, the two were able to paint a better picture of her. McCord began publishing scientific papers and books on criminology years before receiving her doctorate from Stanford University. Her work focused particularly on juvenile delinquency and she had been involved with CSYS since 1956, before becoming director.

But in their research, they also found she faced challenges as a woman in academia. This included losing a research fellowship when she left her abusive husband and having to relocate across the country with her two sons in the midst of her doctorate.

Editor’s Picks

During their research, Paterson said they found letters McCord sent to her research team in which she asked that, when sending follow-up letters to the study’s participants, the team refer to her as “Dr. McCord” and avoid using her first name so she wouldn’t be immediately identified as a woman.

“She was worried that would discourage the men from continuing to participate in the research if they realized she was a woman,” Paterson added. “It goes to show the consciousness she had around how her identity might influence the work. She was dedicated to conducting high-quality research and wanted to maintain the high level of continued participation that the study was experiencing.”

The researchers also found that McCord experienced negative phone calls and people yelling at her in public about her work.

The research could not totally ascertain how McCord’s identity played into the negativity she received during the reporting of the results; her experience aligned with other studies that have found women in leadership roles are more likely to face prejudice. Furthermore, she continued to display strong leadership, which helped her persevere.

Despite the initial backlash to the results of the midlife check-in, McCord’s findings made an impact. Her work led to new advances in delinquency prevention programs. McCord’s findings also prompted a new generation of delinquency prevention studies.

“There’s value in all different types of research, including archival research where you’re interviewing a smaller number of people,” Paterson said. “We really wanted to highlight how her actions were real sources of epistemic justice. She was really instrumental in reorganizing the resources of the study and allowing it to continue by the high rigor Richard Clarke Cabot set up in the 1930s. And we wanted to celebrate what the study means to our field, especially because of McCord’s identity as a woman.”