How string theory helped solve a mystery of the brain’s architecture

Using the same math employed by string theorists, network scientists have solved a standing mystery about the brain’s architecture.

How efficient is your brain? Since the 1940s, scientists have hypothesized that the connections between neurons took the shortest route between two points, a straight line from neuron A to neuron B. But recent observational data have largely contradicted this hypothesis.

When a model scales up from a few points on a two-dimensional surface to thousands of them in three-dimensional space, all of them interacting and connecting in uncertain ways, the most efficient routes become complex mathematical problems.

In tackling this problem, new research from the Network Science Institute at Northeastern University made a surprising discovery: Some of the same mathematics used to describe string theory, which attempts to make sense of the quantum realm, could be used to solve the question of why neurons branch and connect as they do.

The article, “Surface Optimization Governs the Local Design of Physical Networks,” appeared on the cover of Nature Magazine this month.

Wiring up your brain

Beginning in the 1940s, says Northeastern University distinguished professor Albert-László Barabási, scientists hypothesized that the brain’s neurons would optimize their connections by picking the shortest route, “because it’s very costly to build wiring.” Biological systems, generally speaking, want to preserve their energy use.

Scientists call these path-of-least-distance rules “minimization principles.”

However, Barabási continues, as more detailed maps of the brain were made possible by improved imaging technologies, it became clear that neurons weren’t behaving according to the expected minimization principles.

For instance, he says, if a neuron splits, the way a tree branch might split into two smaller branches, the prevailing theory suggests that the two smaller branches would have to be in the same plane. Observations of the brain’s neural network, however, show this not to be the case. Instead, they observed many small branches pointing off at right angles, perpendicular to one another.

The newer datasets also contradicted several other predictions made by the prevailing theory, he says, adding that “there was a need for a new theory.”

So Barabási and his intercollegiate team set out to determine “whether minimization principles really play a role or not in these physical networks,” he says, leaving the case open. Maybe minimization principles, at least in relation to the brain’s architecture, would prove completely groundless.

Math and the human brain

Csaba Both, a network science Ph.D. candidate and co-author on the project, says physical systems simply don’t optimize for their total wiring length. What scientists had previously failed to account for was the fact that neurons, no matter how small they are, are still “physical objects made of material,” and that material restricts how the network is capable of forming.

Barabási and his team developed a new methodology they call surface minimization, which suggested that instead of simply trying to minimize length, physical networks minimize their surfaces, “which naturally explains their branching geometry and connectivity,” Both continues.

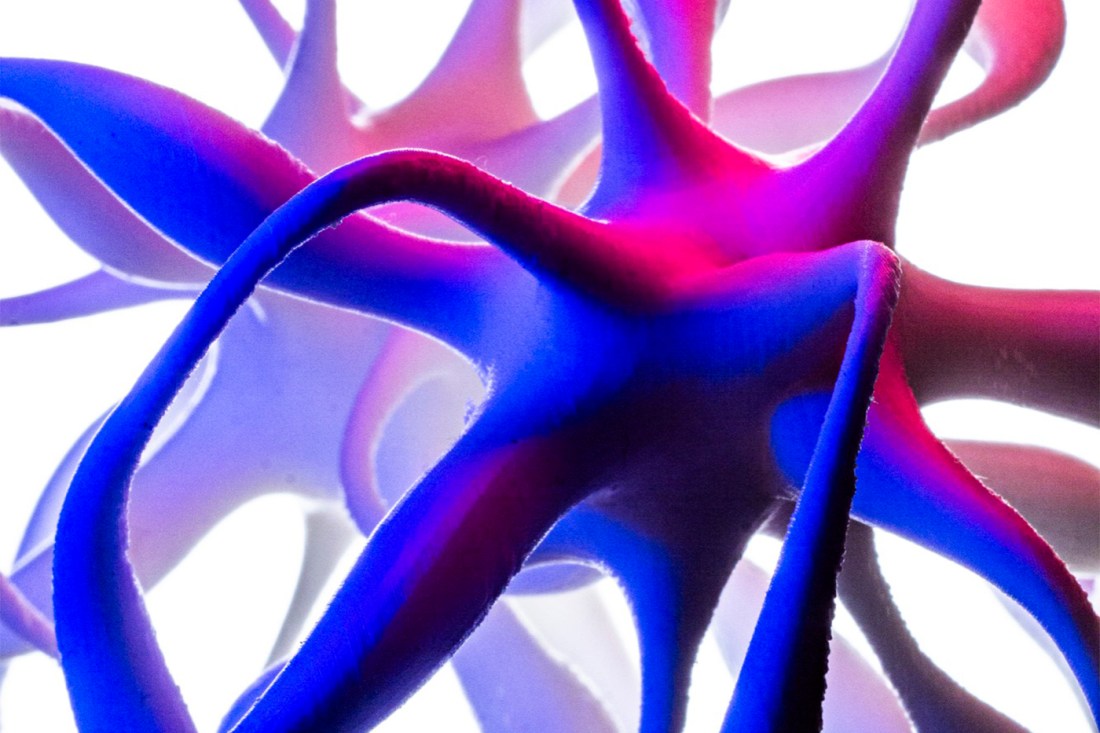

The research article, “Surface Optimization Governs the Local Design of Physical Networks,” graced the cover of Nature Magazine.

Barabási likens it to a mosaic made of many small patches.

“It’s a mathematically very, very, very, very complicated problem,” he opines, “because surfaces are very complicated.” But they were in for a breakthrough, a realization that the mathematical approach to solving the problem already existed, albeit in a different discipline: string theory.

String theory is the sometimes-controversial — as it’s so difficult to verify experimentally — attempt to explain the strange quantum world that undergirds reality, according to Space.com. It imagines the smallest subatomic particles (smaller than protons or neutrons, smaller even than the quarks that make up those other particles) not as particles at all, but as vibrating one-dimensional “strings.”

The breakthrough came from Xiangyi Meng, the first author on the story and Barabási’s former post-doctoral student, now an assistant professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, who recalled that the strings in string theory “are effectively three-dimensional trees whose surface needs to be minimized,” Barabási says. In modeling string theory, astrophysicists and cosmologists rely on something called Feynman diagrams, named for physicist Richard Feynman, a Nobel Prize laureate, to do just that.

Editor’s Picks

They found that the same mathematical toolkits developed by string theorists in dealing with Feynman diagrams, when applied to both the brain and other kinds of physical systems, could predict with a high degree of accuracy how neurons connect.

A cosmological mind?

“We’re not saying that string theory and the brain are similar,” Barabási notes, heading off at the pass any claims that the brain might be a macrocosm of the quantum world. Rather, it’s the math that functions on both scales. “They have to minimize surfaces,” he says, referring to his string theorist colleagues, “we have to minimize surfaces.”

Barabási cautions that this is fundamental research and that real-world applications of their discovery are likely still years away. They have, however, laid the groundwork for a better understanding of how the brain develops, potentially providing “deeper insight into how networks balance efficiency with functional demands,” Both says.

Future research, Both continues, will try to understand how surface minimization impacts the actual function of physical systems, and not just in the brain. The math, he says, seems to apply to physical systems from the brain to the vascular system to coral reefs.

“The biggest surprise is the very existence of this relationship between the string theory field and the surface minimization problem,” Barabási says, “and how it solves an almost 80-year-old mystery.”

The solution to this mystery is now possible because “only in the last five years have we started to have accurate, three-dimensional maps of individual neurons,” he says.

This is really “frontier research,” Barabási adds.