This award-winning concept could help millions of diabetics shop smarter

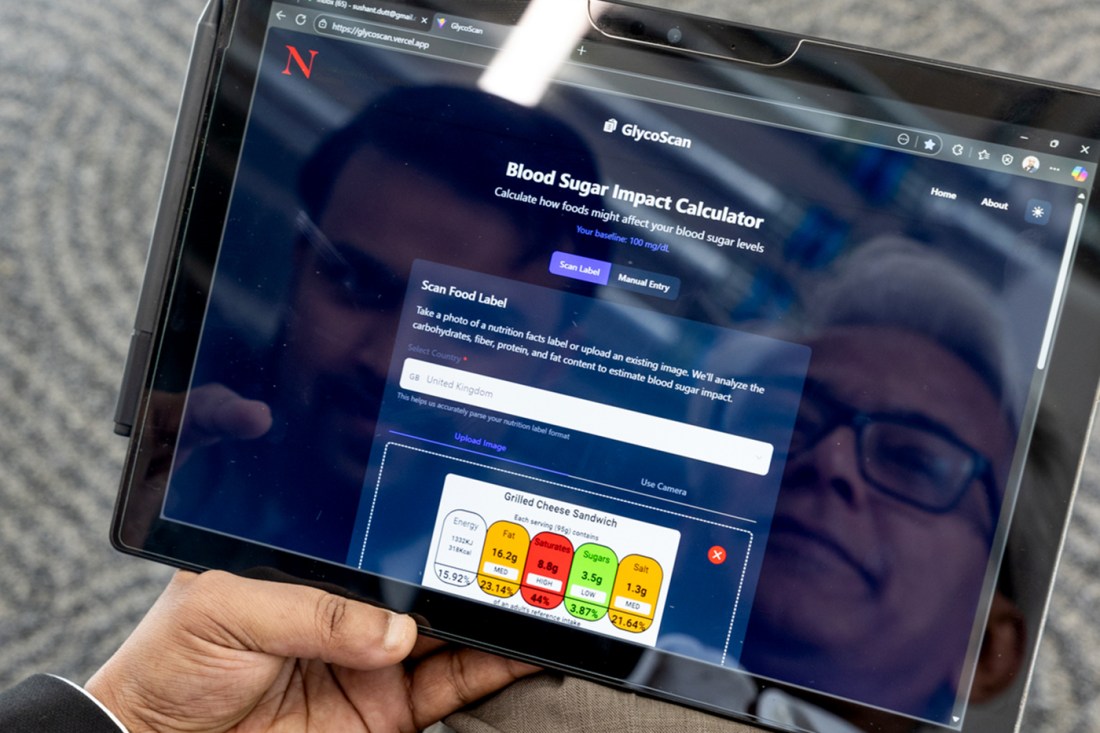

GlycoScan, an app designed by graduate Sushant Dutt that shows users how a shop-bought food product could spike their blood sugar levels, won a Globee innovation award.

LONDON — When the diagnosis arrived, Sushant Dutt could not quite believe what he was hearing.

The doctor was telling him that he was officially one of 4.6 million people in the United Kingdom living with diabetes. The condition is caused when blood glucose levels become too high.

“That was a surprise to me,” says Dutt, a Northeastern University graduate. “I said ‘Really?’ And they said yes — you can’t eat this, this and this. My life actually changed that day.”

The type 2 diagnosis acted as a trigger for what Dutt, who was studying for a master’s degree in artificial intelligence and technology leadership in London at the time, did next.

The 50-year-old’s next few visits to the supermarket proved frustrating and confusing as he strived to alter his diet and avoid foods that could cause his blood sugar levels to jump dramatically. As he squinted at food packaging labels, Dutt had an idea: What if AI could do this for people like me?

“I started asking,” explains Dutt, “can we use anything in advanced technology, like artificial intelligence or deep learning or anything in the large language models, to help these people? Even if it is just 1%, it doesn’t matter. I don’t want to be a game-changer necessarily but just to provide a little help. And that’s how the whole project was conceived.”

Out of that idea, GlycoScan was born. Dutt used Google’s open source Vision AI to create software that could scan product labels and extract their health data. An in-built AI algorithm then is able to process the information to tell the user within seconds whether its contents are likely to spike glycogen levels in their blood and, if consumed, how long it will take for those levels to return to their usual levels.

The concept was the central part of Dutt’s master’s dissertation thesis — “Predicting and preventing glycaemic spikes utilizing AI Vision” — and, after testing it with the public as part of his research, he is currently looking to bring it to market.

The graduate’s invention has not taken long to be noticed. The father of one, who originally hails from Kolkata in India but lived in the United States for eight years before moving to London, was diagnosed with diabetes in January, submitted his thesis in the summer and by September was receiving global recognition.

He was named “Social Innovation Entrepreneur of the Year” at the 2025 Golden Bridge Awards — also known as the Globee Awards — for Innovation. His dissertation supervisor, associate professor in project management Muhammad Khan, was also named as an awardee.

Editor’s Picks

The eight-hour time difference between the Globee’s base on the West Coast of the United States and the U.K. meant someone called Dutt at 3 a.m. to tell him he was a gold award winner.

Dutt recalls that, in his half-awake state, his initial reaction was one of disbelief. “I couldn’t believe it because I never imagined that this was going to happen,” he says. “For me, it was just an academic project.”

It was when seeing the comments made by the judges, made up of industry experts, that it sunk in. “That made me reflect that I might have underestimated this product,” Dutt adds.

According to Globee, the gold award “honors the recipient’s remarkable accomplishments and sets a benchmark of excellence for peers across industries,” adding: “It is a testament to the winner’s hard work, vision, and lasting impact in their field.”

Khan, who was involved in fine-tuning the product, says GlycoScan has potential to reap health benefits for a large swath of people. “I think that this technology can, or has the potential, to save lives,” he says.

The academic explains that when testing the app on shop products, the pair were shocked to find that a sandwich registered as having a more dramatic effect on blood sugar levels than a slice of pizza.

“For me, the award was completely unexpected but it was so encouraging,” Khan continues. “This has served as a provocation to really push on.”

Dutt, who previously co-founded his own technology company and worked on Wall Street for an investment bank, feels the same way as he and Khan now collaborate to turn GlycoScan into a commercial reality. The hope is that millions of diabetics who have smartphones could use this product to improve their day-to-day lives.

He believes it could bring hefty cost savings to the National Health Service in Britain, where he is currently focusing his efforts. But the market could be even larger.

In the United States, 11% of the population was estimated to have diabetes in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The World Health Organization says the number of people living with diabetes rose from 200 million in 1990 to 830 million in 2022.

“The future is extremely bright,” says Dutt. “I look at the future of the GlycoScan and I think that it can be easily commercialized.”