Northeastern grad takes on China’s monopoly of rare earth metals with thriving clean startup

China controls more than 90% of the world’s rare earth metal production. With Phoenix Tailings, Nick Myers found a way to process them more cleanly and in the U.S.

You might not know them by name — and even if you do, you might not be able to pronounce them — but rare earth metals are in every part of your life.

These 17 materials are in everything from cellphones, computers and TVs to electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators and missile guidance systems. They are so valuable that they’re at the center of U.S.-China trade relations, as China, which processes more than 90% of the world’s rare earth metals, agreed to export them to the U.S.

But China isn’t the only place where these precious metals are processed.

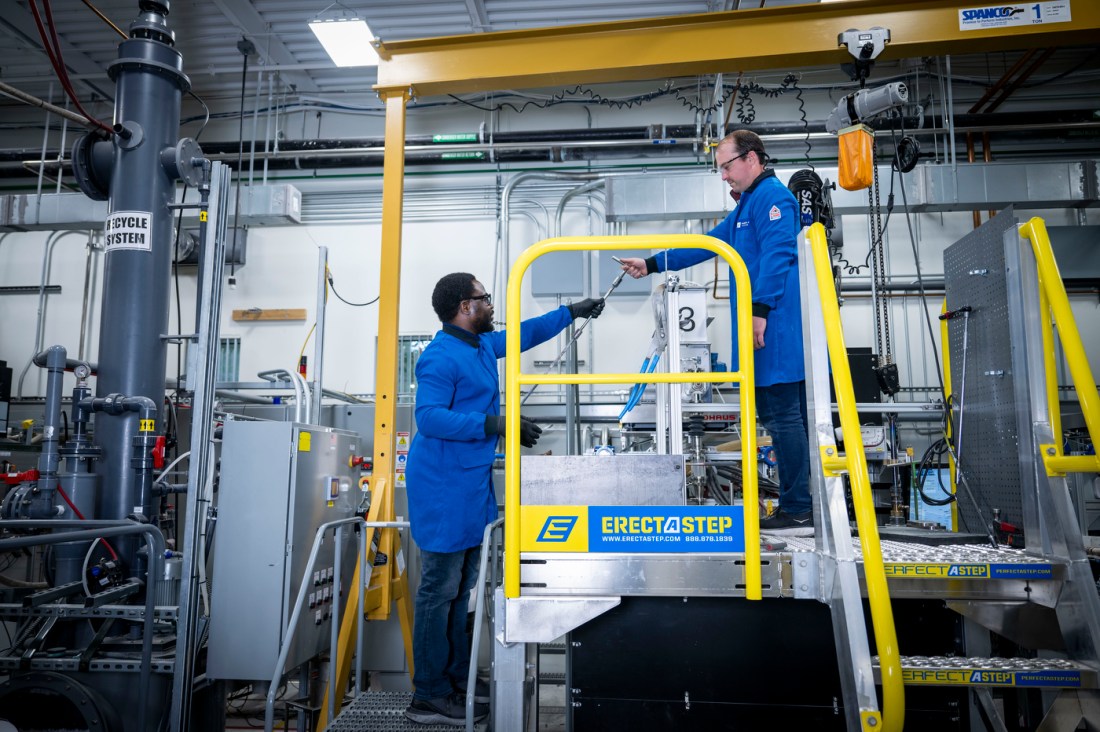

“There’s 97% of the world’s supply chain [in China], and we’re one of the only producers in the Western world, and we operate in Burlington, Massachusetts, producing and shipping out commercial grade rare earth metals,” says Nick Myers, CEO and co-founder of Phoenix Tailings.

Myers, who graduated from Northeastern University with an MBA in 2017, and his team hope to do something very few others in the world of rare earth metals are doing: clean it up. Myers says the dirty secret in the process of rare earth metal production is that mining these 17 metals produces a lot of toxic waste and carbon emissions.

Early on, Myers and his co-founder and CTO, Thomas Villalón, realized this was a huge problem for the industry and the planet. They set out to find a solution, which turned into Phoenix Tailings’ refining process.

“Honestly, we just wanted to find a way to help the world,” Myers says. “If we could make them here, cost competitively without the waste, wouldn’t people really want that?”

At first, the answer from investors was firmly, “No.” However, in talking with customers, Myers realized there was an appetite for the idea.

They created an initial prototype for the refining process in a Cambridge backyard with $7,000. Phoenix Tailings uses a model called predictive complexation, an algorithm-based approach to understanding which chemicals will react with which system in the refining process. It allows the engineers to understand which chemical reactions will produce toxic emissions and which won’t.

The whole process is built on tailings, the materials that are left over after separating valuable ore from the rest of the mined material. Phoenix Tailings takes these leftovers, pulls out rare earth concentrates and then separates each rare earth metal, turning them into a powder-like oxide. That powder is then processed into the final metal.

This year, Phoenix Tailings raised around $80 million in its most recent round of funding, with hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts already lined up.

“Turns out people do want a supply chain that’s not reliant on one country and doesn’t have super toxic waste,” Myers says.

Myers admits that building Phoenix Tailings has been laced with Myers’ experience at and connections to Northeastern.

He was able to take the initial concept for Phoenix Tailings through IDEA, the university’s student-led venture accelerator. His experience founding the Huntington Angels Network, a student-run organization that connects startups with angel investors, also became key to the company’s early success.

The company’s leadership team is also made up of Northeastern graduates, and it routinely takes on Northeastern co-ops. More foundationally, Myers took what he calls “the Northeastern mindset” and applied it to his business. It’s an approach that they still use today.

“We work through everything,” he says. “We troubleshoot, we identify problems, we fail fast and we grow from that. That’s the way we’ve been able to be successful. We’re the grittiest people around –– we don’t give up.”

That iterative, nimble approach has helped the company scale production from 40 metric tons per year in its Burlington facility to 400 metric tons per year in its larger New Hampshire-based operation. For context, the Department of Defense uses about 500 metric tons per year, and U.S. demand tops 10,000 tons.

Myers is heartened by the U.S. government finally catching on to what he and his team have been doing. The news around the rare earths deal struck with China only highlights the need for more diverse sources and more domestic production, he says. The need to do it cleaner is the next step.

“Ninety-seven percent of anything coming from one place is horrible, and the fact that it’s used in everything is a big problem,” Myers says. “That’s just a monopoly. The first rule you learn in business class is monopolies crush innovation, they crush competition, they hurt the end consumer.”