Squid are some of nature’s best camouflagers. Researchers have a new explanation for why

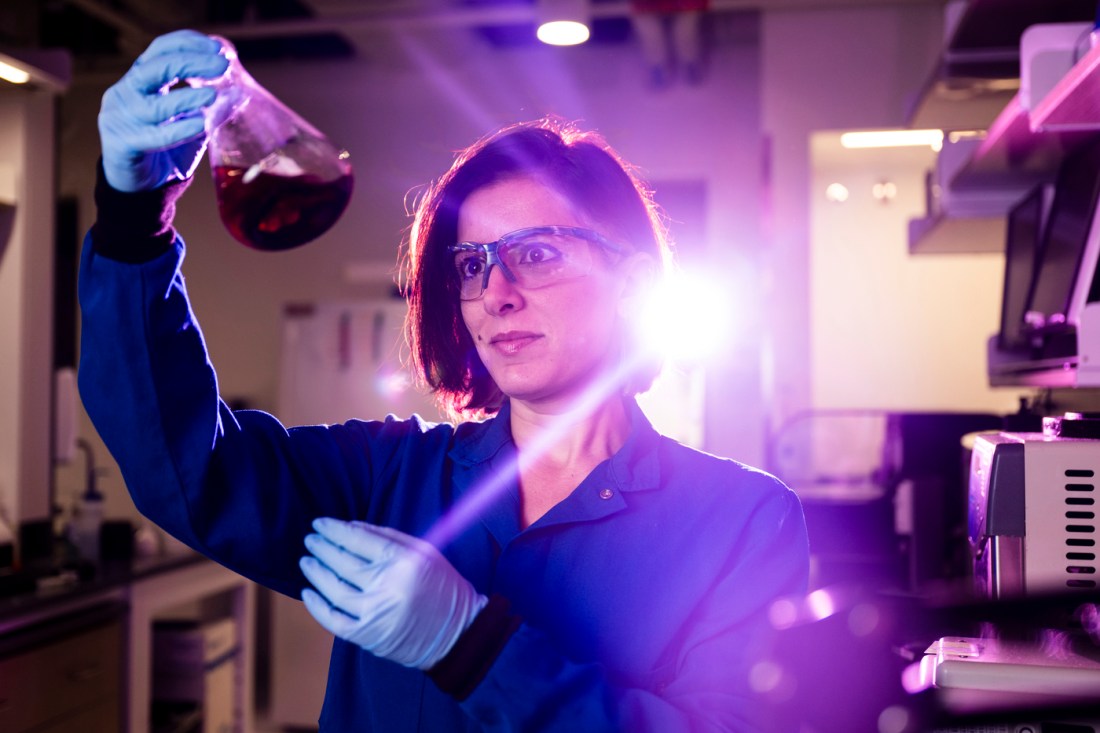

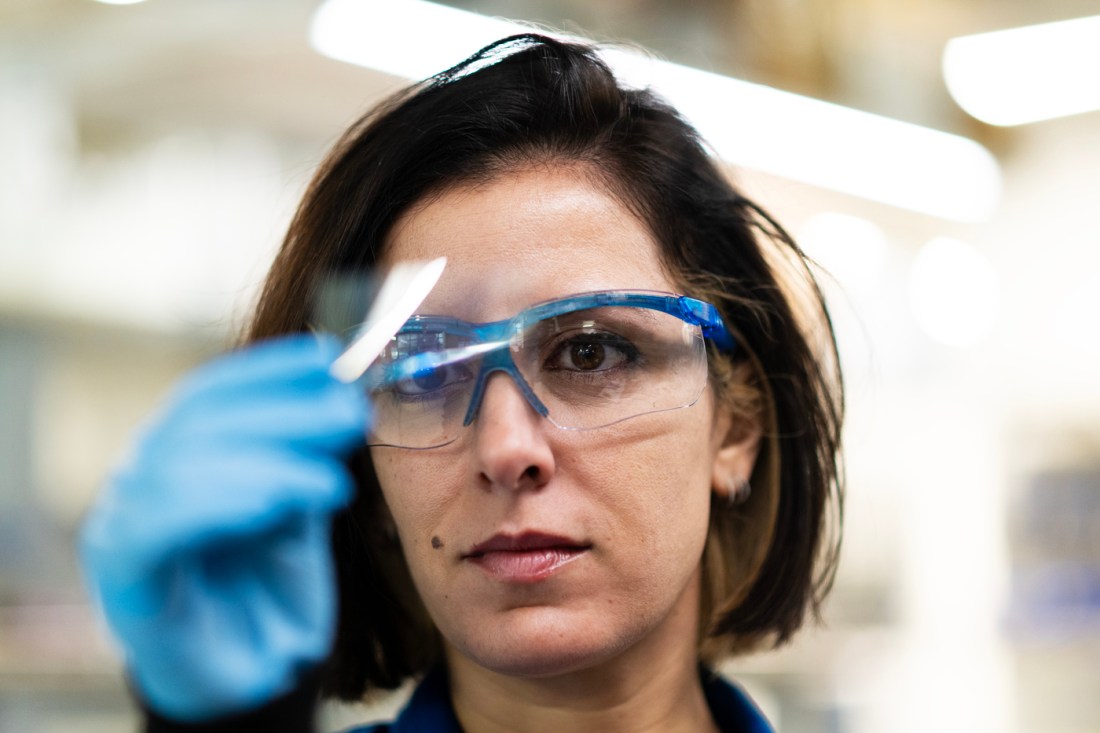

Northeastern’s Leila Deravi found new evidence that chromatophores, pigmented organs in the bodies of squid that help them camouflage, are like organic solar cells that the animals use as hyper-efficient light sensors.

Nature is full of masters of disguise. From the chameleon to arctic hare, natural camouflage is a common yet powerful way to survive in the wild. But one animal might surprise you with its camouflage capabilities: the squid.

Capable of changing color within the blink of an eye, squid, along with their cephalopod relatives octopi and cuttlefish, have used their natural camouflage to survive since the age of the dinosaurs. However, scientists still know very little about how it all works.

Leila Deravi aims to change that.

An associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Northeastern University, Deravi’s recently published paper in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C sheds new light on how squid use organs that essentially function as organic solar cells to help power their camouflage abilities. Deravi says it’s a breakthrough in how humans understand these “super-charged animals,” one that could impact how we humans interact with the world.

Deravi has long been fascinated by cephalopods, particularly squid. Her Biomaterials Design Group at Northeastern is focused on investigating how these animals camouflage, with the aim of using those natural mechanisms to create new biomaterials.

More recently, her lab has been looking at the one specific part of squid biology — chromatophores — which is where the latest discovery was made.

Chromatophores are pigmented organs that sit all over the squid’s skin. They have muscle fibers on the outside that are filled with neurons, allowing the animal to neuromuscularly open and control these pigment sacks based on what’s in their environment.

Together with iridophores, which act as a kind of photo filter, adding greens and blues to the chromatophores’ reds, yellows and browns, they give squid the ability to change color within hundreds of milliseconds, distributing the color all over their body.

“To have something sense the colors around it and distribute [them] within hundreds of milliseconds is really insane,” Deravi says. “It’s not something that’s easy to do, especially in a living system that’s under water.”

It has been commonly understood that chromatophores are a kind of colorant that operate similar to pixels in a TV display, but Deravi found that they are much more. Her latest research reveals that chromatophores are light sensors that help power squid and their natural camouflage.

“It can see whatever light is on the outside and convert that light into energy and then harvest that energy to help distribute camouflage,” Deravi says.

To test this idea, Deravi and her team built a squid-powered solar cell. They used conductive glass, semiconductors, electrolytes and the chromatophores’ pigmented nanoparticles taken from dissected squid to create a circuit. By focusing solar simulated light on the glass, they activated the circuit and measured how much energy it was putting out.

“We found that the more granules you put into there, the higher the photocurrent response is,” Deravi says. “It’s a direct indication that the pieces of the chromatophore are actually converting the light from the sun simulated light to the voltage, which can complete the circuit and then be harvested, potentially, for a power supply in the animal.”

Featured Posts

The discovery marks the first time anyone has made a connection between the chromatophores in a cephalopod and their ability to generate current.

Uncovering the secrets behind how cephalopods camouflage has a number of applications for humans. Deravi’s lab has already used its findings to design wearable UV sensors that can help prevent skin cancer and produce more environmentally and human-friendly sunscreen, as Deravi has done with her startup, Seaspire.

What’s particularly remarkable, she says, is how efficient this biological system is. Squid are able to change color and distribute that change over their entire body while under water using very little energy.

Understanding more about how squid use their organic solar cells could help a burgeoning field like wearable electronics where size, weight and power distribution are constant concerns. The squid might be the key to developing a truly “living digital skin,” she says.

“If you think about fully wearable stuff, you just have to think about how to make it the most energetically favorable in order to be fully interactive with the surroundings,” Deravi says. “We’re trying to tap into what the blueprint is that the animal uses to do this and how that correlates to adapting to the environment as well.”