Patagonian ‘living rocks’ trace their origins to the beginning of life on Earth

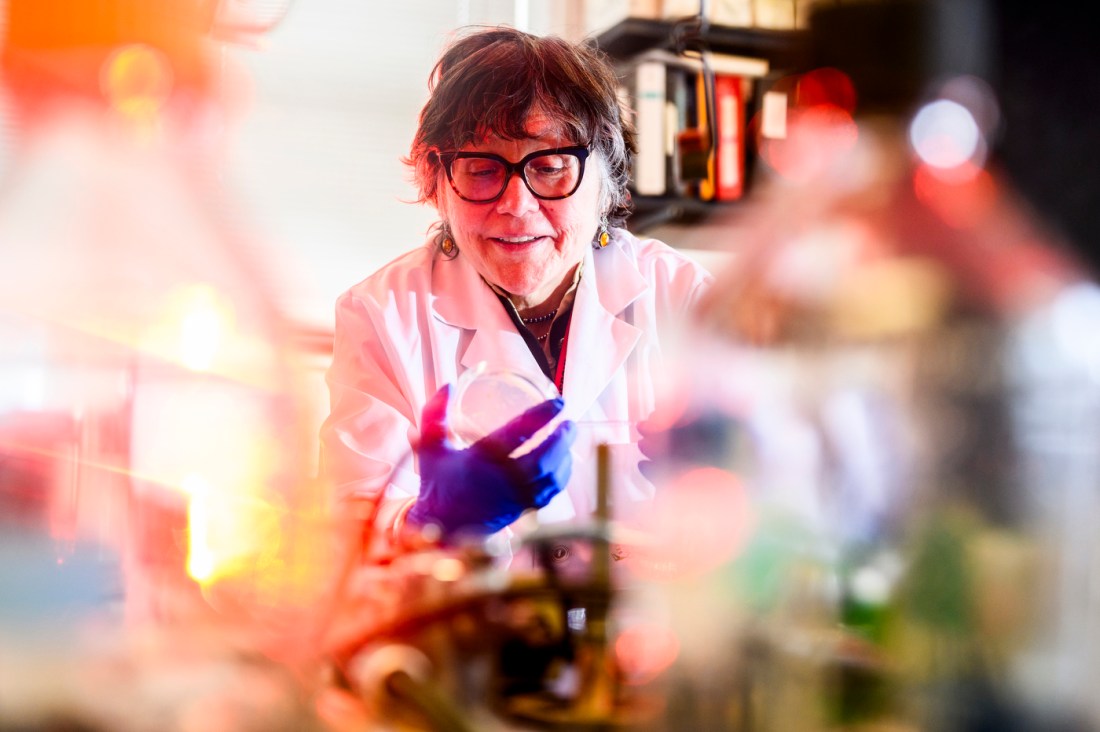

Associate professor of biology Veronica Godoy-Carter has sequenced the genome of a bacteria discovered during a Northeastern University Dialogue of Civilizations excursion to Patagonia.

In the Patagonia region of southern Chile, there are “living rocks.”

While that’s what the locals say, Veronica Godoy-Carter, associate professor of biology and biochemistry at Northeastern University, says it’s a little more complicated than that.

“They’re actually little mountains,” she says, of “giant biofilms that are billions of years old. Literally billions.”

To put that in perspective, the Earth is thought to be about 4.5 billion years old, which means these “rocks” — really bacterial biofilms (a sheet of bacteria only a few cells thick) — have been around a long, long time.

Over the eons, these biofilms have piled up and calcified into forms that look like rocks called stromatolites.

They predate humans, our primate ancestors, maybe even multicellular life itself.

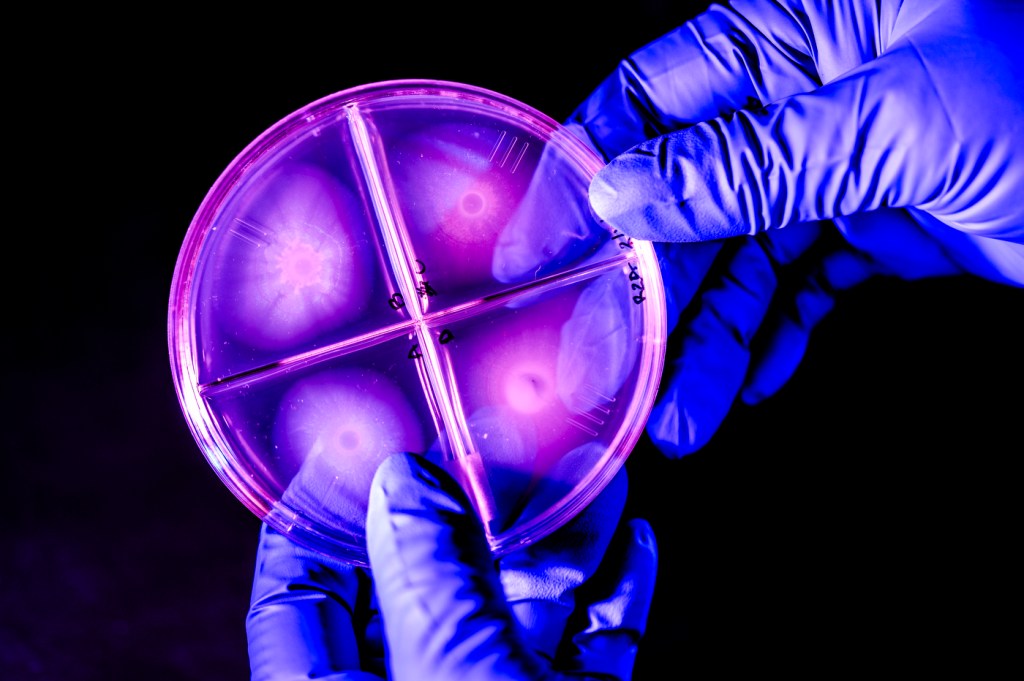

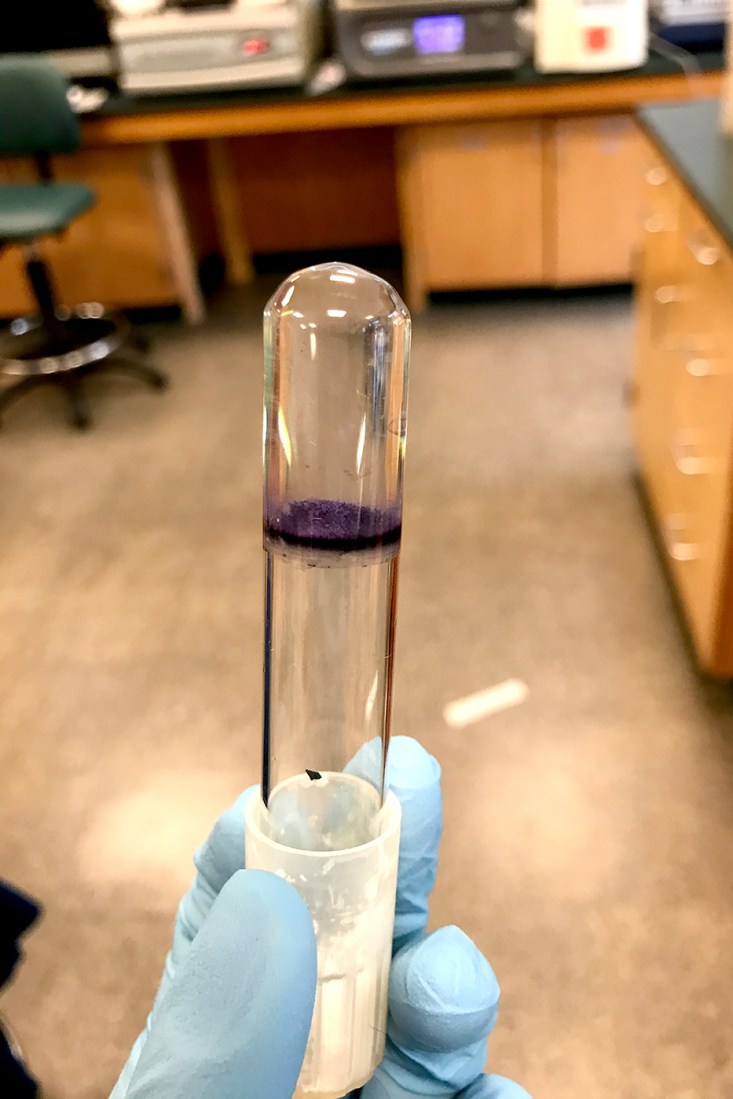

Now Godoy-Carter has sequenced the genome of one of these bacterial colonies, a species within a genus called Janthinobacterium, which is found in soil and water and has a distinctive violet color.

A Patagonian expedition

Godoy-Carter’s excitement is infectious. “Bacteria are the most awesome organisms on Earth. They can live without us, but we cannot live without them.”

Her research focuses on how bacteria adapt to changes in their environment, especially their response to DNA damage and the mutations that may — or may not — occur in response to that damage.

In 2018, Godoy-Carter led a group of Northeastern students and researchers on a Dialogue of Civilizations trip to Patagonia, where they visited these “living rocks” and went hunting for unique bacteria.

Editor’s Picks

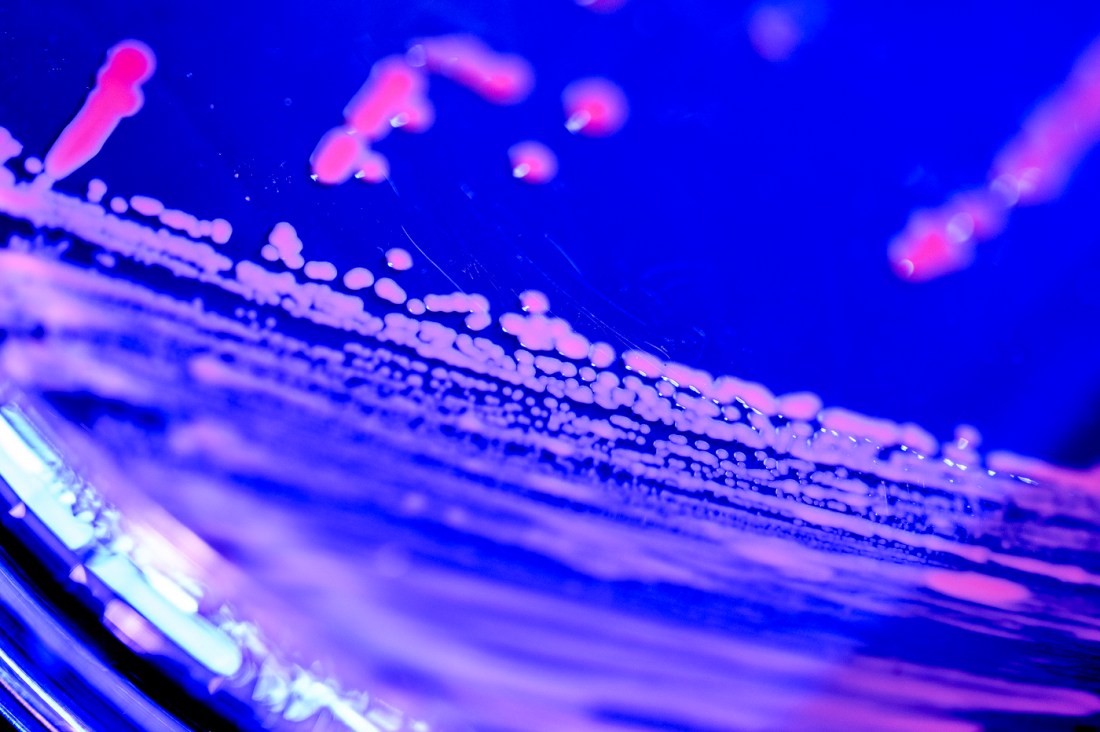

What they found was a brilliantly colored bacteria whose biofilm was strong enough to act like a lid over a test tube, holding back the liquid inside.

The Janthinobacterium Godoy-Carter and her team isolated is also an extremophile, which survives despite being subjected to freezing temperatures.

Janthinobacterium “makes these multicellular communities that are incredibly robust,” Godoy-Carter says. “These types of formations made by bacteria are believed to be, pretty much, the first living cells, organized cells, on Earth.”

While their work is still in the early stages, there’s still “so much fun stuff to do,” she says. “With the biofilms, we can make new plastics, new textiles, maybe we can make the textiles with the pigment, and maybe the pigment protects from UV light.”

A purple bacterium

These multicellular communities were maybe the most obvious reason to pursue this genus, but Godoy-Carter had another: “I love purple,” she says with a laugh.

“My dream was to get a purple bacterium, and I did.”

The pigment likely helps the bacterium protect itself against ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

“The next thing is to know, can we molecularly work with the original bacterium?” Godoy-Carter continues. Bacteria extracted from outside environments “are very difficult to work with, because they have their own systems, and they are not familiar to the lab. They tend to change, they shut off.

“They’re like, ‘Man, I’m not going to cooperate.’”

Now that Godoy-Carter and her team have sequenced Janthinobacterium’s genome, however, they’ll be able to isolate the particular genes they’re most interested in studying, and can effectively plug those genes into other, more laboratory friendly bacteria.

“This Janthino[bacterium] doesn’t want to cooperate,” she says, “so we need to move it to a different background.”

Systems biologists call these host bacteria chassis, like the frame of a car to which other parts can be mounted. “We need to find a good chassis,” Godoy-Carter says. “And I think we have one.”

Godoy-Carter says that her whole expedition team was excited by the discovery and what they found in the lab. The same undergraduate researchers — and others who accompanied her to Patagonia — worked with the Janthinobacterium back in the United States.

The students “feel that they are contributing to the science — and they are,” she says.