Northeastern grad’s new foundation provides menstrual products for those in disaster zones

The Fihri Foundation, led by Northeastern grad Ceylan Rowe, has shipped more than 250,000 products to people in need in the U.S. and 16 other countries.

Northeastern graduate Ceylan Rowe is on a mission to ensure that women and girls in disaster zones have access to safe, hygienic menstrual products.

Since Rowe launched the Fihri Foundation last year, she says, the organization has shipped more than 250,000 pads, tampons and other menstrual products to 17 countries, including to survivors of floods in Bangladesh, earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, and hurricanes in the United States.

Rowe, who graduated from Northeastern in 2003, says the nonprofit fills a gap in disaster relief.

“There are a lot of great organizations that focus on food and shelter, rightfully so, but our focus is on period products. We’re trying to fill that void,” she says.

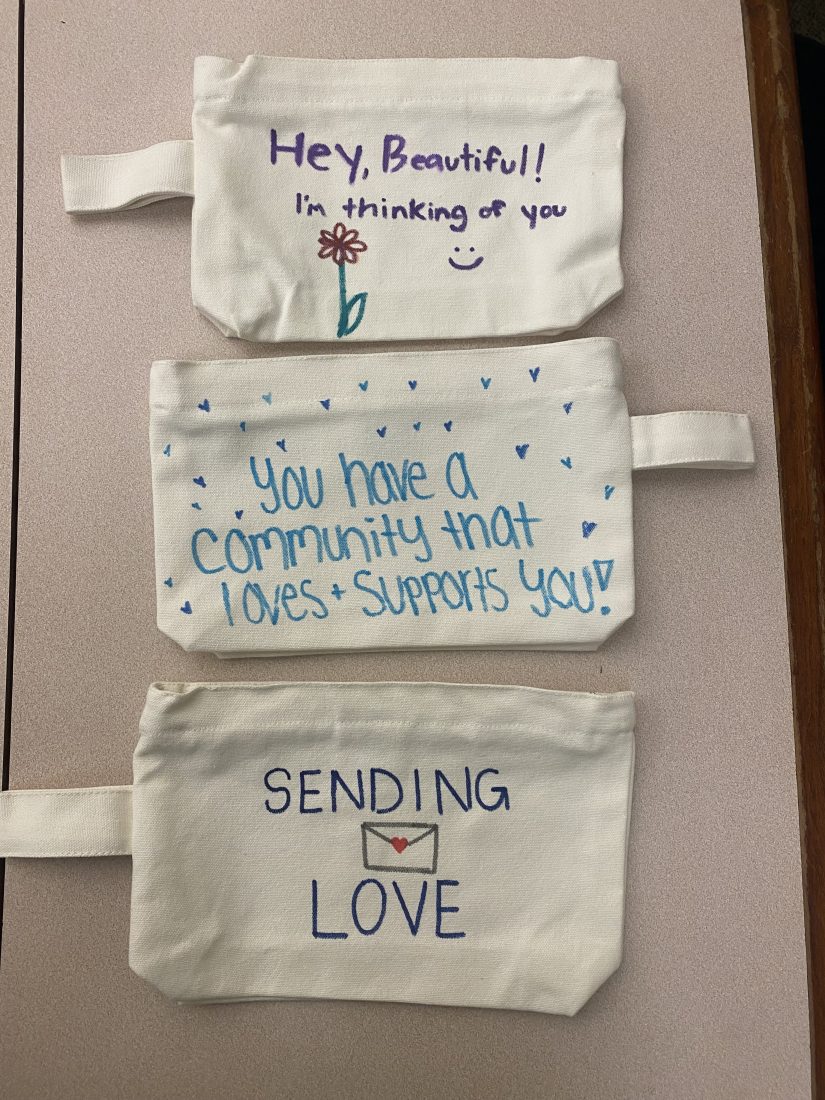

The need for menstrual products does not end because of a natural disaster, Rowe says. “In the worst moments of these women’s lives, we just want to provide hope. This is very much a question of comfort and dignity.”

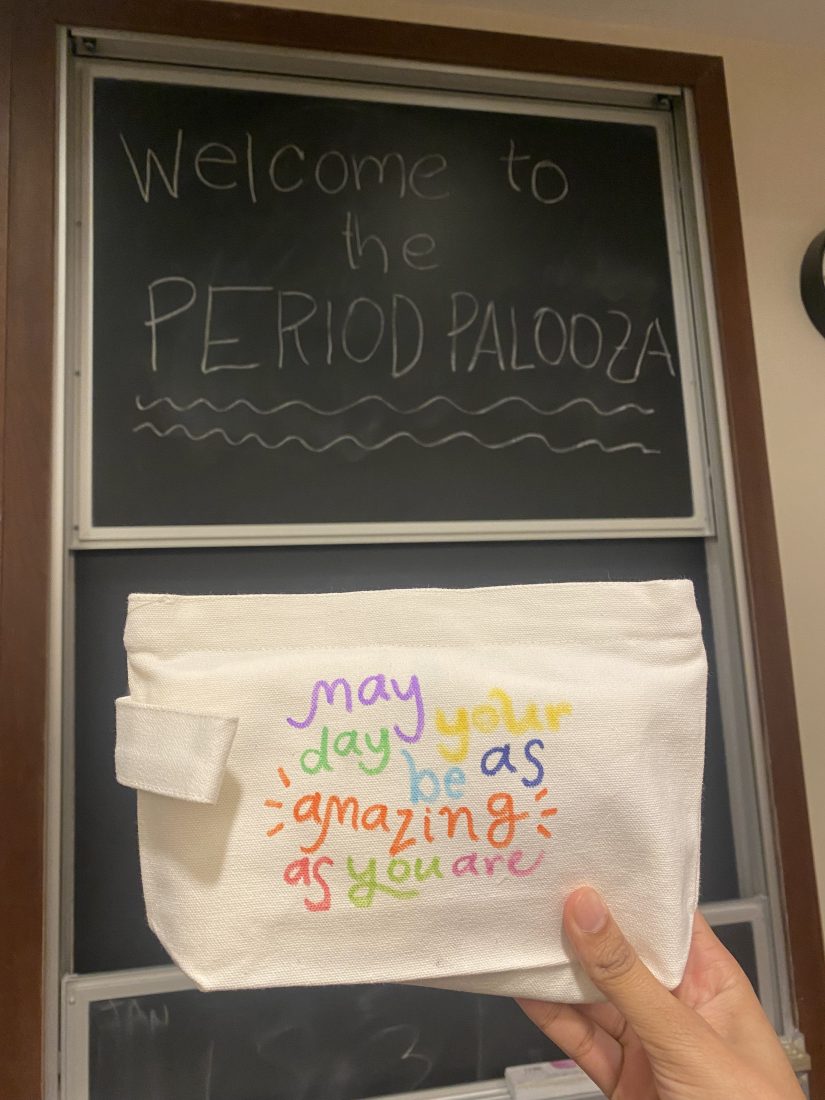

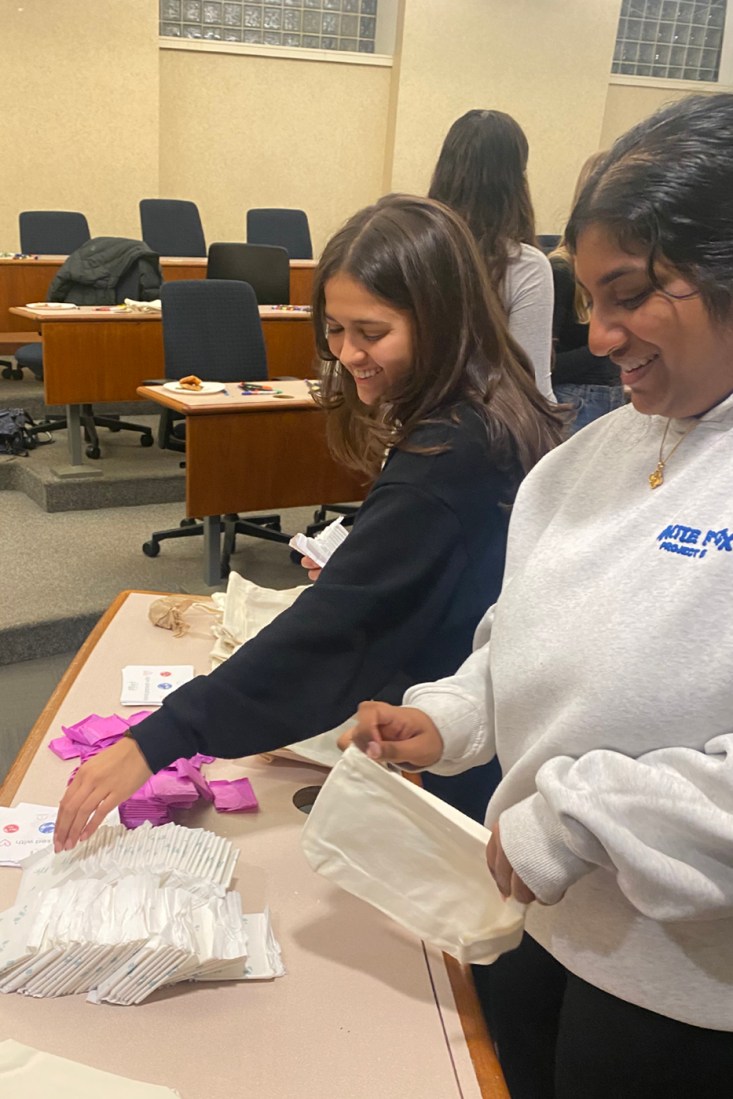

Volunteers pack white canvas kits with menstruation products and handwritten messages of hope during hygiene health collaborations, including one in November at Northeastern at which students put together 300 kits for victims of hurricanes Milton and Helene.

Another such event is scheduled from 6 to 7 p.m., Feb. 27, at Room 112 in Hastings Hall for victims of the Los Angeles wildfires.

“I grew up in a conservative town in Indiana. Periods were never talked about, nevermind period poverty,” says third-year Northeastern student Prachi Patel, who is co-founder of the Menstrual Equity Club, which is helping sponsor the Feb. 27 event.

But “this is an issue that affects so many people across the world,” Patel says.

The kits usually contain a mix of pads and tampons and panty liners, Rowe says.

“Overseas, we found the request has been for pads. We usually put a month’s worth of period products in each kit. We’ve sent period underwear and cups as well when they’ve been requested,” she says.

The kits have made their way to refugee camps in the Middle East, as well as to food pantries in the United States and the United Kingdom.

“We strongly believe women should not be using tent pieces, mattress pieces or dirty rags to manage their period,” Rowe says. “We’re here to make sure that they have products that are better for their bodies and that are sanitary and hygienic.”

As a teenager visiting family in Turkey, she saw firsthand what it was like for women and families to live in tents after a major earthquake hit the area and killed more than 17,000 people.

“I saw people who had really just lost everything,” Rowe says.

She says that the association between poverty and lack of menstruation products was made clear to her when she served on the MetroWest Commission on the Status of Women.

During a women’s advocacy day at the Statehouse, Rowe says she heard about eighth graders teaching sixth graders how to use toilet paper as a menstrual pad.

“I said, ‘How is this happening in Massachusetts?’ I did not realize at the time that this is a local issue,” she says. “In fact, one out of four students misses school in the U.S. because they don’t have period products.”

Globally, 500 million women and girls lack access to menstrual products each month, Rowe says.

After an unsuccessful run for state representative five years ago, she turned her attention to starting the foundation to advocate for women across the globe.

The mother of a 17-year-old son and 15-year-old daughter, Rowe says she wanted her daughter and her peers to have access to sustainable products.

“I launched Fihri as a mom who wants to make sure that not just my daughter but all of our daughters throughout the world have access to education, access to financial stability and access to a fulfilled life,” she says.

“Women and girls need access to period products so that they can go to school, go to work, have financial stability,” says Rowe, who named the Fihri Foundation after a ninth-century Arab woman, Fatima Al-Fihri, who started a mosque that evolved into a university.

Rowe says her interest in advocacy work stems from her time at Northeastern, where she studied political science and international affairs and had former Gov. Michael Dukakis as her adviser.

Editor’s Picks

She’s heartened by how comfortable the current generation of students is talking about menstruation and menstrual equity.

“That has not been the case in my generation and before,” Rowe says.

Maria Restrepo, co-founder of Northeastern’s Menstrual Equity Club, says she was inspired to take on the challenge of addressing this “poverty” after researching the subject during a Dialogue of Civilizations trip to South Africa.

“I learned that menstruation is often taboo and often dealt with in unsanitary ways, and I knew something had to change,” she says.

“Partnering with Fihri has allowed the Menstrual Equity Club to merge our passion for accessible period care with their expertise in advocacy, policy change and service, empowering us to advance our mission and create a lasting systemic impact both on campus as well as communities in need,” Restrepo says.

Rowe says she loves working with college and high school students “because they are really the ones pushing the menstrual equity conversation forward by asking their schools to supply free menstrual products. If there’s free toilet paper, why shouldn’t there be free period products?”

Rowe says there’s a cost to not addressing this poverty of menstrual products.