This Northeastern researcher has been tracking activists’ efforts inside Communist China

The Great Translation Movement on X is using social media to “challenge the authoritarian regime” in Beijing, according to assistant professor Chunyan Wu.

LONDON — Activist journalists living outside China’s censoring-regime are successfully using social media to “challenge” Beijing’s “authoritarian regime,” a paper by a Northeastern University researcher has found.

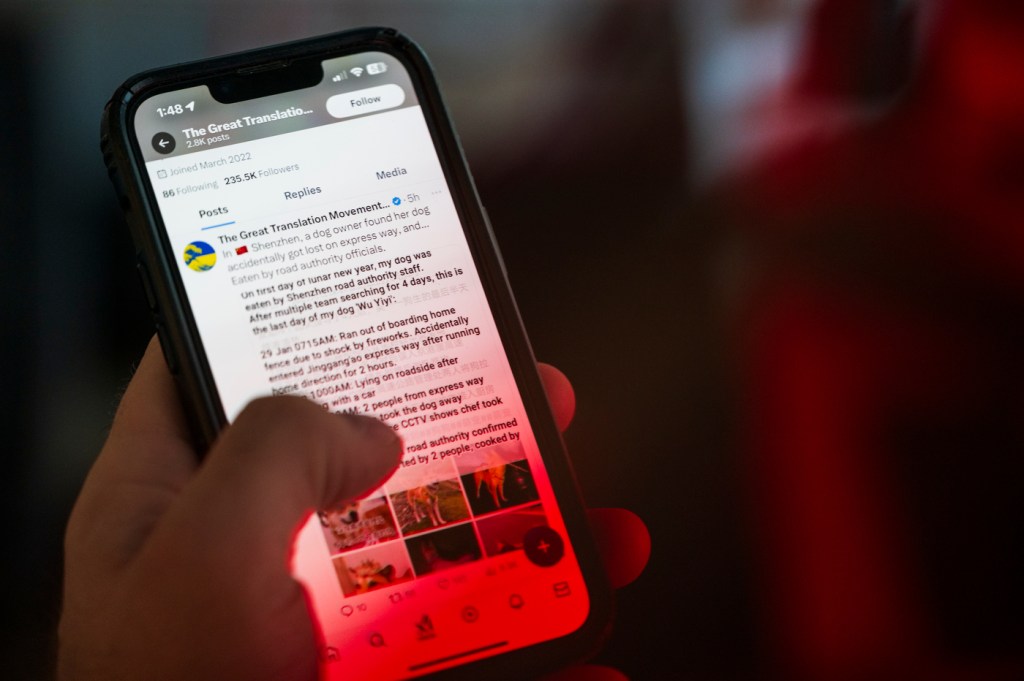

Chunyan Wu, assistant professor in communication studies at Northeastern in London, was part of an effort to analyze tweets by The Great Translation Movement, an account on X (formerly Twitter) that she says combines journalism and advocacy to highlight what is happening inside China to a global audience.

The academic says the international initiative, which has more than 235,000 followers, is part of a reaction to President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party’s tight control of the internet and media in China.

“China’s current political climate has become increasingly restrictive,” says Wu.

“The government’s strict censorship and also state-driven propaganda have limited free speech on domestic platforms, creating an online echo chamber that supports official narratives. At the same time, pro-government internet users actively report dissenting opinions and promote state rhetoric.

“In response to these restrictions, some activists inside China use censorship-circumventing strategies, and those living abroad have turned to global platforms — such as X, for example — to make their voices heard.”

For their paper, “Curating activist journalism to defy China’s ‘mainstream’ narrative on X (Twitter)” published in the Critical Discourse Studies journal, Wu and her U.K.-based colleagues — Altman Yuzhu Peng from the University of Warwick and Yu Sun from the University of Glasgow — combed through posts published by The Great Translation Movement between March and December 2022.

During that period, they found that the dissidents running the account had looked to expose how the Chinese government was “aligned” with the narrative of Russia — another communist state — when it came to domestic commentary about Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, which started Feb. 24, 2022.

That is despite Beijing stressing in public statements at the time that it was a neutral player in the conflict, stating that the “sovereignty of all countries” must be respected.

The 23-page paper highlights how The Great Translation Movement shared what was being said about the invasion on Chinese state-controlled television, including falsely claiming that Ukrainian soldiers and anti-war protesters were actors being paid by Kyiv.

Wu says the activists, by sharing screenshots accompanied with English translations, were able to “highlight the extremist undertones” in Chinese reporting of the conflict in Eastern Europe, while also “creating a sharp contrast between the factual critiques and the emotionally charged nationalist rhetoric.”

Another tactic used by the account was to share articles produced by trusted news websites, including the BBC, that were reporting on what was happening socially in China, ranging from incidents of violence against women to the impact of life under strict COVID-19 restrictions.

“These events were widely censored on domestic platforms [in China],” Wu continues. “So the activists created vivid visuals and then offered a factual description on international social media to expose these injustices globally.”

Editor’s Picks

Wu says their analysis shows that The Great Translation Movement has been successful at creating a “public space for addressing critical issues such as authoritarian control, disinformation and social injustice” — discussions that tend to be censored on domestic platforms in China.

Those behind it, she argues, have been able to use a global online platform to “challenge the dominant narratives” in communist-controlled China, amplify marginalized voices and “transform domestic Chinese concerns into visible international conversations.”

But the account is not without its “shortcomings,” the academic points out. The Great Translation Movement can be guilty of offering a “simplified representation” of the Chinese people, with some posts equating pro-government internet users “with the entire Chinese population.”

“This over-simplification risks ignoring the complexity of Chinese civil society, including the dissenting or ambivalent voices within the country,” Wu says. “Such framing can exaggerate the xenophobic sentiments, particularly in a global context where anti-China rhetoric is mobilized for political gain.”

In that respect, Wu says the account is in danger of “mirroring the tactics of the information campaign seen in authoritarian propaganda,” which looks to smear whole populations by tarring it with the actions of extremists.

Without addressing such concerns, The Great Translation Movement risks undermining the “progressive goals” that its activists claim to represent, Wu states.