French railway company’s involvement in Holocaust revealed in Northeastern grad’s podcast

“Covering Their Tracks” details a Holocaust survivor’s daring escape from an Auschwitz-bound train and his decades-long attempt to hold the rail company accountable.

On Nov. 6, 1942, Leo Bretholz, 21, was stuffed into a French train, rushing through the night, bound for Auschwitz-Birkenau. As the reality of the situation dawned on Bretholz –– death was at the end of the line –– he made a decision that would save his life: He jumped.

Jumping from the moving train and into the dark of the night, Bretholz and his friend, Manfred Silberwasser, escaped the horrors of Auschwitz. Out of the more than 1,000 Jews and others on that train, Bretholz was one of four to survive the Holocaust.

That’s only part of the story told in a new five-part podcast, “Covering Their Tracks,” which chronicles Bretholz’s escape and later attempts to hold SNCF, the French national railway company responsible for deporting him to Auschwitz, accountable. Of the 76,000 Jews and others who SNCF transported on its trains, only 2,000 survived.

Created by Matthew Slutsky, who graduated from Northeastern University in 2003 with a degree in political science and a passion for storytelling, the podcast is a story of courage, persistence in the face of horror and the frustrating imperfection of justice and accountability.

“Leo was part of [this lineage] and he told his story, and by taking up the mantle and creating a podcast that would have not been created otherwise, I am helping to extend that lineage in a small way,” Slutsky says. “That feels, especially after Oct. 7 and in this current moment, very important, far more important than I ever could have imagined when we started the project.”

Slutsky has been obsessed with telling stories in one form or another since he graduated from Northeastern with the intent of hitting the campaign trail with Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry. With a career spanning political campaigning, advocacy work –– he co-founded the social issue petition site Change.org –– and documentary filmmaking, Slutsky was captivated when he first heard Bretholz’s story in 2011.

The details of his escape were incredible enough. “If you were writing a movie script about a superhero, it would be his story,” Slutsky says. But the details of SNCF’s involvement were more shocking.

“I had already heard the very traditional narrative that the French were conscripted by the Germans and that they had to, at gunpoint, go and execute the Germans’ vision for the annihilation of Jews,” Slutsky says. “This story turned that on its head.”

Slutsky obtained invoices SNCF sent to the Germans, showing it was “paid per head per kilometer for every person they transported to a camp,” Slutsky says. Internal communications show SNCF debating whether it would be more profitable to transport humans or beets.

But the story of SNCF and Bretholz doesn’t end after World War II –– that’s only half the story of “Covering Their Tracks.”

Featured Posts

After years spent on the run in Europe, Bretholz eventually moved to the United States, settling in Maryland in 1947. Years later, SNCF followed suit. In 2011, Keolis, an American subsidiary of SNCF, was bidding to operate commuter trains in Maryland. Bretholz was outraged.

Working with other survivors and Raphael Prober, the attorney who first told Slutsky about this story, Bretholz launched a lawsuit and campaign to block the company from securing a contract with the state.

He found some measure of success: Due to the advocacy of Bretholz and other survivors, then-Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley signed a bill, the first of its kind, requiring the company to disclose the role it played in the Holocaust if it wanted to secure a contract with the state.

Then, in 2014, Bretholz learned that Keolis was angling to land a $6 billion contract from the state of Maryland to build a light rail system. Bretholz once again made it his mission to block the company from operating in the state, unless it owned up and paid reparations to the remaining survivors it had transported to the camps.

Later that year, Bretholz died at the age of 93.

In the end, some measure of justice was accomplished, even though Bretholz was not there to see it. A 2014 agreement between France and the U.S. established $60 million in reparations for those deported by French trains to concentration camps. The French government started making payments in 2019.

However, Slutsky says the thing Bretholz and so many other survivors really wanted –– an honest apology from SNCF –– still hasn’t happened. French President Emmanuel Macron acknowledged the country’s role in the Holocaust in a 2017 speech, but SNCF “has still not apologized,” Slutsky says.

“It is imperfect justice because you can’t have perfect justice when you’re talking about millions of people dying,” Slutsky says of the reparations settlement. “Ultimately, what these people wanted was an acknowledgement of the pain they or their relatives went through. It was imperfect and it was not a perfect settlement, but it was a step that they never thought they would get to.”

In some ways, this story remains unresolved. Slutsky hopes the podcast shines a light not only on SNCF’s history but the importance of people like Bretholz who never stop leaping into the dark in search of justice.

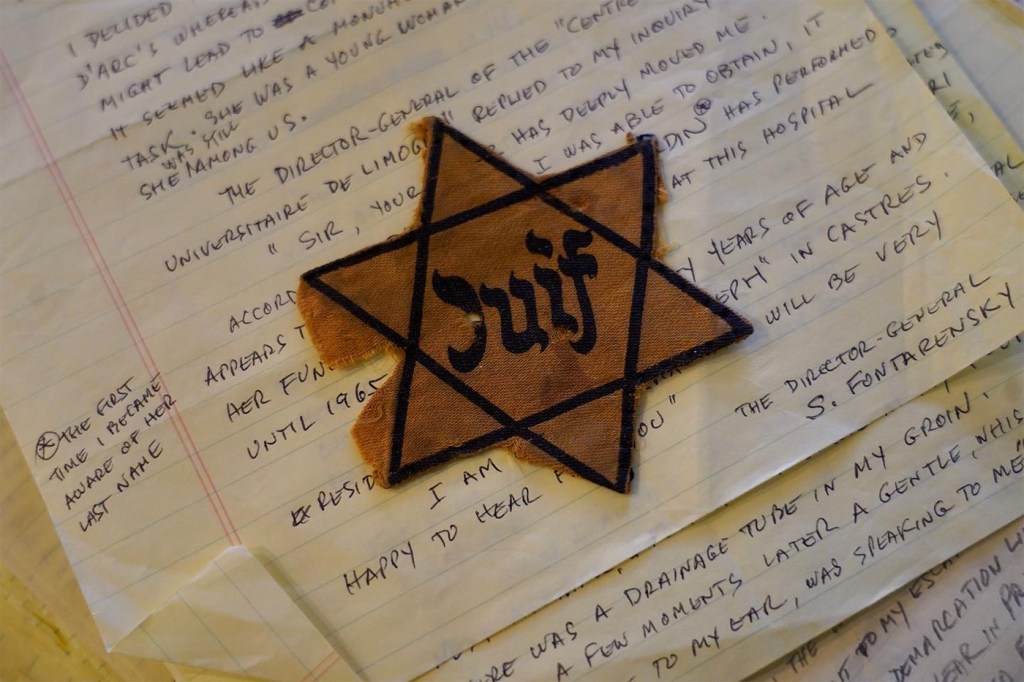

Bretholz famously carried two things with him at all times. One was the Star of David badge that was sown on the shirts of all Jews under the Nazi regime. The other was a massive book that was a detailed log of every person deported to a concentration camp by SNCF. Under “Convoy 42,” Bretholz is listed as deceased.

“He would carry it around and say, ‘This is me. I was supposed to be dead, but I got off,’” Slutsky says.

“He’s such a fascinating example of someone who could have kept his mouth shut,” Slutsky adds. “At the end of his life, in the last year or two, everyone I talked to said that this process of testifying in Congress and doing media was weighing on him … and he went on and continued to do this because he felt obligated to do it.”