Northeastern engineering students named inventors on groundbreaking patent that removes PFAS from water

Two Northeastern University chemical engineering students have helped develop a new method of removing potentially harmful PFAS — known as “forever chemicals”— from drinking water, a discovery that could have major implications in providing clean water for thousands of communities throughout the United States and the world.

The discovery was made while the two were chemical engineering co-ops at Practical Applications Inc., a wastewater treatment facility in Woburn, Massachusetts. They were working on the method with Practical Applications CEO Gary Broberg, a Northeastern graduate.

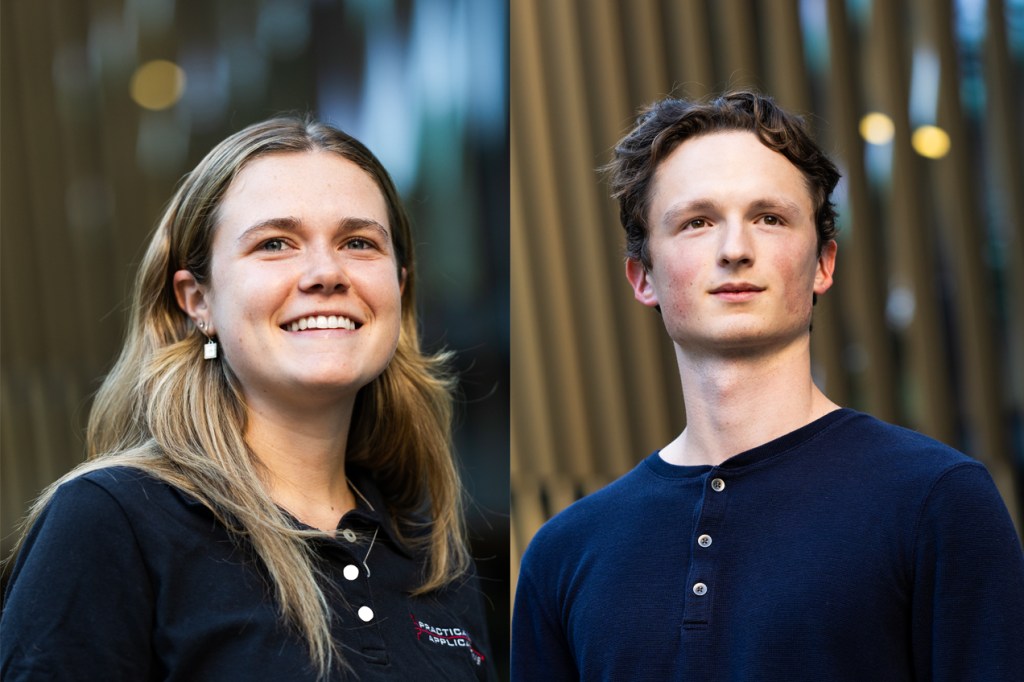

Graham MacDonald and Hannah Giusti, third-year students at Northeastern, say the process is more cost effective and less energy intensive than conventional treatments used today.

MacDonald, Giusti and Broberg have been named innovators on a provisional patent documenting that process. The trio say the process can bring concentrations of PFAS in water bodies below the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s detection limit of 0.82 parts per trillion.

“Truthfully the way I feel is lucky,” MacDonald says. “The entire team was very motivated. It was fun to work on, especially when the results were good. I was introduced to a lot of things I wouldn’t have otherwise.”

Giusti says the experience has greatly influenced the field she wants to work in after graduation.

“I’ve always been into environmental science, and this project is a really great motivator and confirmed it would be a really good field for me because it’s something I’m really passionate about and interested in,” she says.

PFAS is short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. They are known as forever chemicals because they can take upwards of a thousand years to dissolve in the environment. These man-made chemicals were used in the development of clothing, cookware, furniture and industrial machinery up until around the early 2000s.

Featured Posts

In recent years, PFAS have made national and international headlines as communities have learned that these substances have found their way into drinking water sources and can be harmful to human health, even in extremely small amounts.

“The health effect is that it attacks your digestive system, so that’s pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, intestinal cancer, colon cancer — all those cancers are believed to be related to exposure to PFAS at the parts-per-trillion level,” says Broberg, who graduated from Northeastern in 1989.

The way water companies remove PFAS from drinking water today involves using activated carbon to extract the substances from the water. The extracted PFAS have historically been then discharged back into the sewer system, but increasingly municipalities are requiring the PFAS to be incinerated to prevent these substances from going back into the environment.

What Broberg and the students have developed is a process of breaking down PFAS to their “elemental compounds” without the need for incineration.

“Our process takes that waste and treats it completely so there is no residual,” Broberg says. “That’s really the key difference. That’s a cost savings, but it also prevents it from going back into the environment, so it’s breaking that cycle.”

“What we hope it will do because it is so much less expensive, it will be available to any municipality,” he adds.

Broberg first became interested in treating PFAS after hearing Phil Brown, a Northeastern university distinguished professor of sociology and health sciences and the director of the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute at Northeastern, speak about PFAS at one of his seminars at Harvard University.

Over the years, Broberg has worked with multiple Northeastern students on co-op on this research. Together, Giusti, MacDonald and Broberg made the breakthrough.

“We really stumbled upon a solution,” says Broberg, who couldn’t fully disclose how they developed the process since the patent is still going through the approval process. “We were really just playing in the lab trying different things, and we stumbled upon this.”

“Hannah and Graham did hundreds of samples to just prove the process and get the results that we got,” he says. “They were awesome.”