Northeastern archivist contributes to exhibit on desegregation of Boston Public Schools

Northeastern archivist Molly Brown pulled over 100 pieces of material for an exhibit spearheaded by the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the landmark court decision.

“It’s not the bus, it’s us.”

This is how Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee co-founder Julian Bond described the racist violence he and other students experienced after Boston was forced to desegregate their public schools through court-mandated busing of students to different neighborhood schools. It quickly became a motto to sum up the movement.

The years of activist work that led to the landmark 1974 decision from Judge Wendel Arthur Garrity and the aftermath of it are often forgotten. A new exhibit at the Boston Public Library is looking to change that.

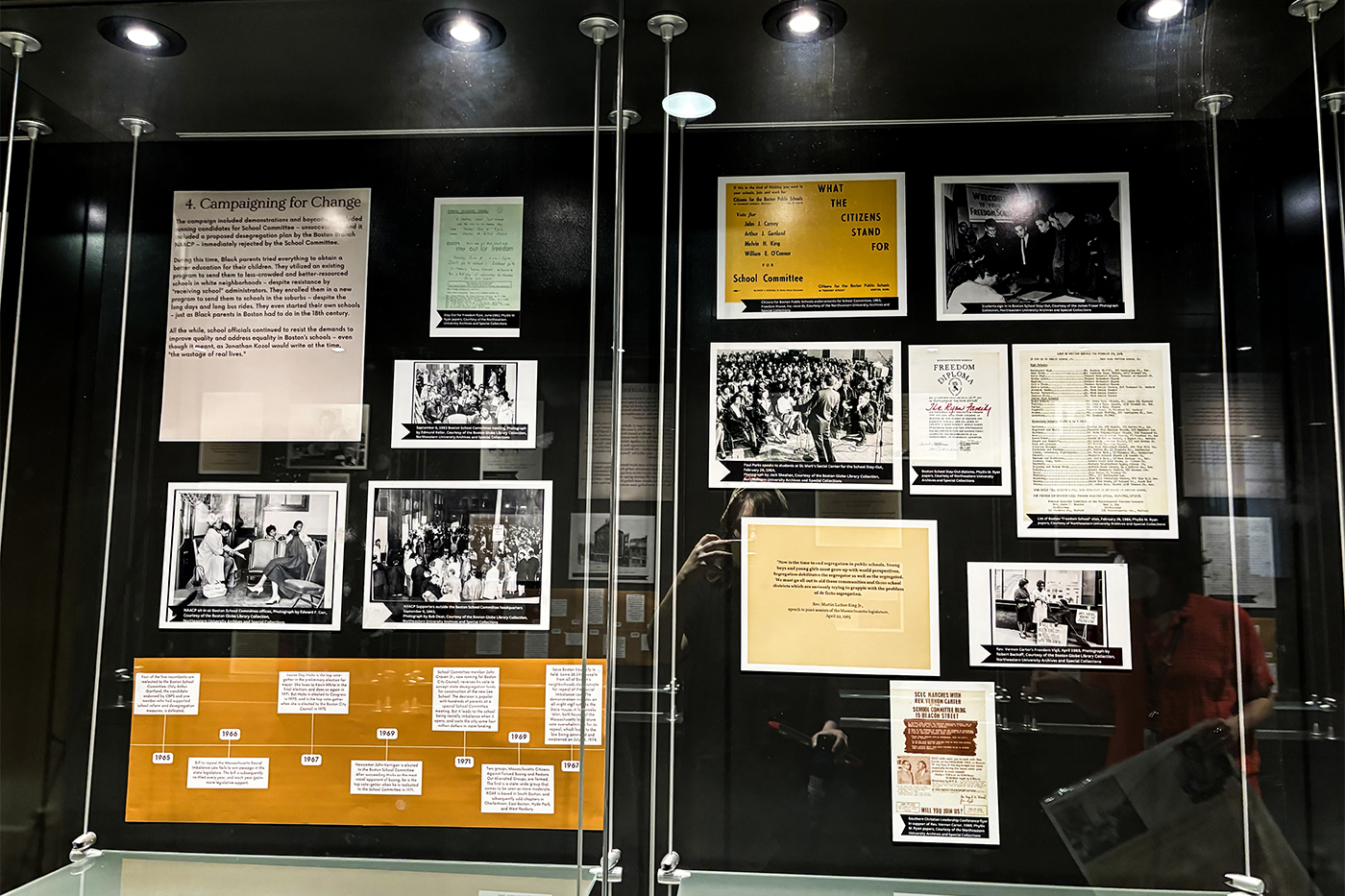

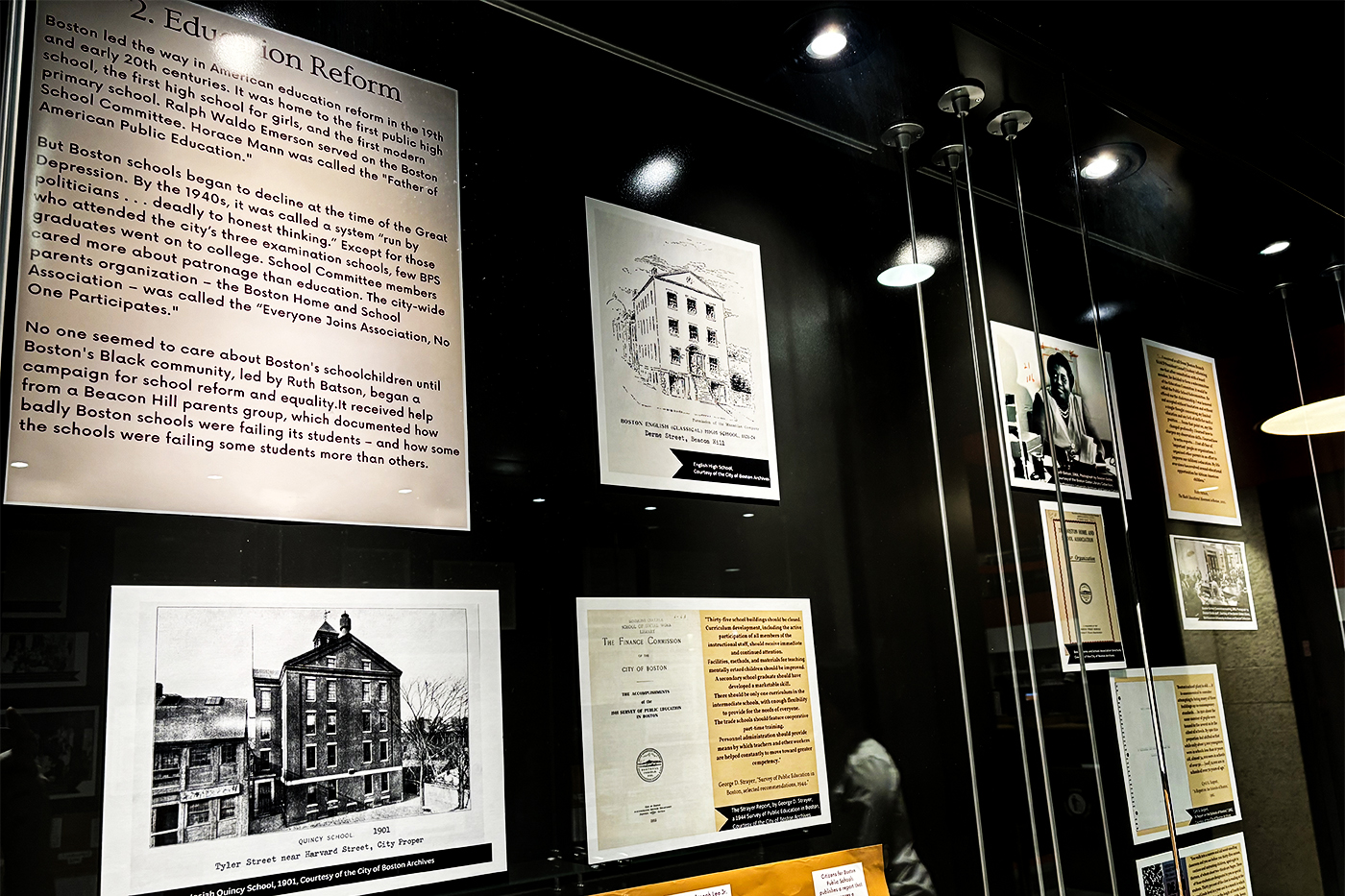

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Garrity decision, the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative put together a 20-case exhibit titled “A History of Public Education Reform and Desegregation in Boston,” in part with Northeastern University reference and outreach archivist Molly Brown.

Brown, who has been working in the Northeastern archive for nearly seven years, was already working with the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative to provide reproductions of records about the history of school desegregation for them to bring to events. Lew Finfer, one of the co-leaders of the initiative, then came up with the idea of a larger exhibit in a public space where people could learn more about this “long and complicated” history in honor of the anniversary of the ruling, Brown said.

“Even though it’s the 50th anniversary of the Garrity decision … there was so much (activism) that predated that, in particular by Boston’s Black community,” she added. “It’s really important for the city of Boston, including the students that are still impacted by the reverberations of the decision today, to see that history reflected. For anybody that is new to Boston, the whole history may be surprising. 1974 was very late for desegregation to occur, and … it is so striking what a catalyst 1974 was and yet, how many other movements and catalysts there were prior to it.”

Editor’s Picks

The exhibit was curated by community historian Jim Vrabel, who came up with a narrative that includes the overlapping movements and timelines that led to the 1974 decision and the ones that followed it. Brown’s role was to find archival records to help illustrate this history. She worked with the city of Boston’s historic archives and other Boston universities to gather materials. She also utilized Northeastern’s collection, which already includes a lot of material on Boston schools’ desegregation.

Some of the records were picked by Vrabel’s request, others were volunteered by the other archivists. When they were done, Brown designed and installed the exhibit in Gallery J at Boston Public Library’s Central Branch. It opened Sept. 18 and will be up through Jan. 7.

The goal was to embody the phrase Bond uttered at the rally and find materials that brought the extent of the movement and the people involved to life. Vrabel ended up crafting an exhibit with 10 chapters looking at the history of desegregation in Boston; each chapter features an introductory narrative as well as a timeline and accompanying archival material. Overall, there are over 100 pieces of material in the exhibit.

“The initiative (felt) that looking at the actual records of the event was really helpful in catalyzing community conversation and so they wanted to have a more curated and wider breadth of materials available in the exhibit,” Brown said. “What this exhibit does is give representation to the people involved in the wider, messy history of advocacy for resources in Boston Public Schools for students of color. It’s giving space to widen the conversation and for people to themselves within it.”

The collection includes reports written during the period this was going on with certain quotes in them highlighted for visitors and several types of fliers. There’s also images from the Boston Globe’s archives, Brown said, and documents that highlight the critiques of the Boston School Committee and community responses at the time.

“Sometimes you look at photos of people protesting the buses and you think that that’s the only narrative,” Brown said. “But there were also freedom schools and other unique protests that really helped. So it was trying to find the images that could speak to that labor.”

To find the right materials, Brown leaned on Vrabel and Ruth Batson, who was a key organizer and activist throughout this and wrote a book about it that was published by Northeastern. She also tapped on her own skills as an archivist, leaning on the advice she gives students when teaching them how to use the archives: find a point that helps you connect with the history, whether it be a flier or handwritten documents.

Brown tried to include a variety of materials so everyone could find something that resonates while visiting, and to illustrate the sheer amount of work done to desegregate Boston’s schools.

While Brown has collaborated before with community organizations, she said this was a new level of involvement for her when it comes to archival work.

“It is really important for archivists to be active in helping people find the records that help tell stories,” Brown said. “We are not often the experts on the stories themselves. It is the people that are represented in the stories or the people that have done that long community organizing work within those stories. But where I can help is making sure that we get the records that can help speak to it the best.”