From medieval times to the present, London’s migrant history celebrated in new book

A magician from India, discovery at St. Paul’s Cathedral and Vincent Van Gogh’s time on Hackford Road among the many stories in “Cultures of London: Legacies of Migration.”

LONDON — In July 1813, “something next to miraculous” happened in Pall Mall in Central London.

Ramo Samee, described by some as the most famous Indian magician of the time, and his troupe of jugglers migrated to London from British India to try their hand at entertaining a new audience.

They succeeded in Pall Mall, at least in the eyes of essayist William Hazlitt.

“The chief of the Indian Jugglers begins with tossing up two brass balls, which is what any of us could do, and concludes with keeping up four at the same time, which is what none of us could do to save our lives,” Hazlitt wrote of the performance.

Samee performed in London for more than three decades before dying in poverty.

Now, his story is a highlight of London’s diverse history in a new book out of Northeastern University’s London campus that celebrates migrant communities and their role in forming the city’s unique culture.

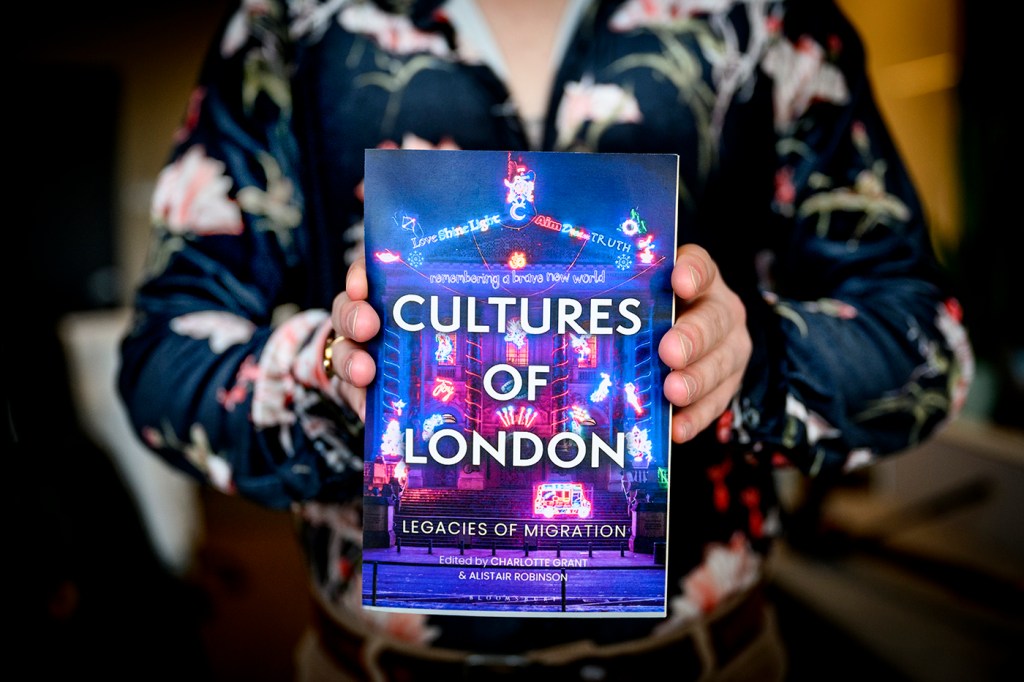

“Cultures of London: Legacies of Migration,” edited by Charlotte Grant, associate professor of English, and Alistair Robinson, an assistant professor, is in bookstores now. A book launch will be held at Northeastern’s Devon House on Jan. 18.

Bringing together 35 authors — including academics, artists and curators, each with unique perspectives on London’s diverse history — the book forms a “kaleidoscopic” image of London from medieval times to the present, with the theme of migration at its center. Nine of the essays are written by Northeastern faculty or graduates in a volume that Robinson says is a celebration of migration and a rejection of recent hostility toward migrants.

Its inspiration came from the Cultures of London course, a core requirement for students studying on Northeastern’s London campus. Originally fashioned as a literature course, Cultures of London has since morphed into an experiential learning class in which students dissect a variety of texts and make visits to cultural centers of London, including the Globe Theatre and the Foundling Museum.

The course opens up students’ minds to a London they may not have imagined.

“The course helps them see aspects of London that they might not have seen, or helps explain some aspects of London that they might not have a narrative to explain,” Grant says.

Migration has emerged as a theme, “an undercurrent of the course,” Grant says, noting that most of the students are visiting scholars and therefore have movement on the mind; they also bring in a plurality of perspectives that enrich the campus environment.

While the book was inspired by the course and “resonates” with it, Grant says, it isn’t tied to it. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Grant and Robinson, who has also taught the course, decided to develop the volume together, using their existing networks to solicit papers while also bringing in unknown voices. Many of the contributors are academics, but some are curators, artists and Northeastern graduates.

“It’s trying to tell different stories from different perspectives,” Grant says.

London’s history is marked by conquest, growth and trade. As the book outlines, it was founded as Londinium by the Romans in the first century A.D., and abandoned in the fifth century, though the Saxons took over an area about a kilometer north. The Norman Conquest in 1066 ushered in a new era of trade. By the 18th century, London had become a major colonial power dependant on the slave trade. In the 19th century it grew considerably in both population and size. Much of it was destroyed during World War II but was rebuilt.

But the book is not a comprehensive history of London, and it doesn’t try to be. Instead, it consists of snapshots of people, places and things forming a “palimpsest of different migrant stories,” Robinson says. It includes well-known figures like William Shakespeare, but also dives into unexpected stories that normally don’t get told.

In one essay, a 14th-century poem describes an unexpected discovery at St. Paul’s Cathedral and challenges Londoners to rethink their past. One tells the story of Vincent Van Gogh’s time spent on Hackford Road in the south of London in the 1870s. Another explores the life of Ignatius Sancho, a Black Londoner known for his letter writing and for rubbing elbows with some of the city’s elite residents. Another outlines the role of beggars and vagrants in early 19th-century London. Yet another explores the history of 19 Princelet St., a house in Spitalfield, and its inhabitants.

What ties all of these topics together? Throughout London’s history, one thing has remained constant: an influx of migrants, many coming for economic opportunities, and some escaping political persecution.

“London is a city built upon waves and waves of different migrant communities coming together,” Robinson says.

The book explores migration of humans that have made up the diverse cultures of the city, but also the animals, plants, objects and ideas that make their way through the global hub. Two chapters focus on water and how the city’s expansion impacted its water infrastructure in the early 17th century; one tells the story of waste management in the mid-19th century; one tells the story of the bus and access to the city in the 20th century; another outlines horticulture moving into the city.

According to the introduction, in this way the book “celebrates the plurality of the capital’s cultures and affirms the importance of migration in the making of the modern city.”

This has become more important in recent years, Robinson says, as the stark reality of racial tensions in the United Kingdom became clear during the pandemic and after the murder of George Floyd in the United States.

Featured Posts

“The importance of migrant communities to the city became starkly visible during the period of the pandemic,” Robinson says, noting that their role in keeping the U.K. National Health Service and transportation sectors functioning was outsized.

At the same time, right-wing anti-immigrant rhetoric has taken hold in the country.

“[The book’s] timeliness was already evident given the rise of nationalistic and new-right rhetoric in the U.K. and Europe, with its unashamed scapegoating and vilification of migrant communities,” reads the introduction.

In the U.K., conservatives have discussed plans to reduce immigration and even to send migrants to Rwanda. At the same time, as the book notes, over 100,000 Ukrainian people have come into the U.K. since February 2022.

One of the book’s goals is to “push against that kind of hostility,” Robinson says.

Instead, it proves that the city’s diversity is what gives it its strength. The book’s introduction highlights a carving in the Museum of London from the Temple of Mithras during the Roman period. As Robinson notes, the stone that makes up the carving is from Italy, the craftsman was likely from Roman Gaul, and the iconography comes from the Persian Empire.

“The carving is not notably skilful and depicts a commonplace scene, but the story that it tells us about London as a city shaped physically, demographically and ideologically by its place in a global network underlies this volume,” reads the introduction.

“It is a story that will surface again and again.”