New research pushes back against charge that Google search engine creates partisan ‘filter bubble’

Is Google’s search engine a neutral arbiter for information, providing a diverse set of sources for any given query, or is it deliberately steering users toward content that aligns with their beliefs?

That’s the focus of new Northeastern-led research published this week in Nature, which focused on trying to parse whether the world’s most visited search engine creates a so-called filter bubble around users in the context of political news or users themselves seek partisan information on their own without significant algorithmic interference.

As part of the study, researchers monitored the online behavior of internet users during the 2018 and 2020 U.S. election cycles through a custom web browser extension. The monitoring tool was designed to measure two specific data points: exposure, or what news sources users encounter when they search for a topic on the Google engine; and engagement, or what news sources users interact with following a search.

The results are based on 102,114 search results for 275 participants analyzed in 2018, and 226,035 search results for 418 participants analyzed in 2020.

The researchers found that the participants’ political leanings, which they acquired through surveys, had a “small and inconsistent relationship” on the number of partisan and unreliable news sources they were exposed to on Google Search, and “a more consistent relationship with the search results they chose to follow.” In other words, there was little to no evidence of a filter bubble.

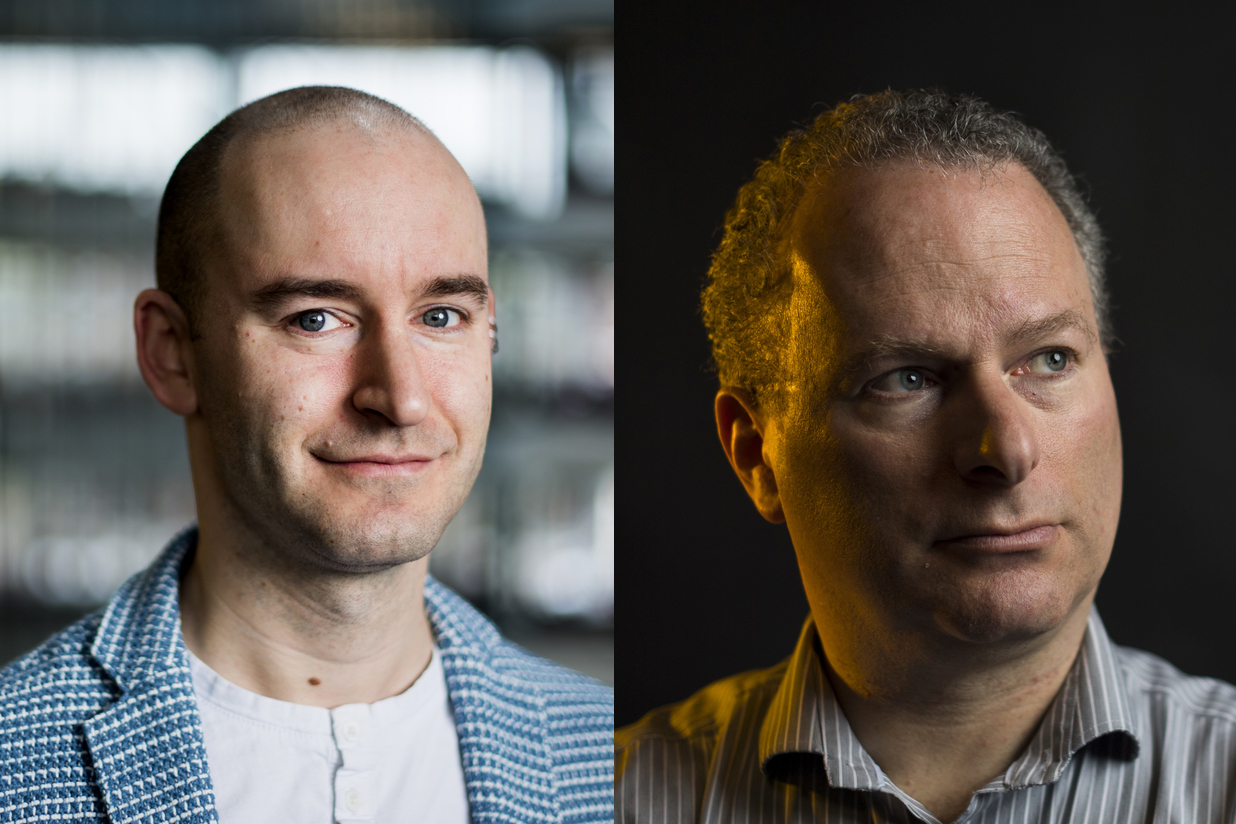

But when the researchers examined what users chose to engage with, they found that people would seek out content that aligned with their viewpoints. “It’s as you would expect,” says Christo Wilson, associate professor of computer sciences and co-author of the paper. “People tend to read news sources that are congruent with their own beliefs.”

The researchers noted that while there have been a great many studies examining the role social media companies have played in steering users toward content that confirms their viewpoints, “further research is needed” as it pertains to popular search engines.

“These findings shed light on the role of Google Search in leading its users to partisan and unreliable news, highlight the importance of measuring both user choice and algorithmic curation when studying online platforms, and are consistent with prior work on general web browsing, and Facebook’s News Feed,” the researchers wrote.

The results are noteworthy because it appears to counter the charge that Google has had a filter bubble problem in which it’s been alleged that the company uses users’ private data to personalize search results. The tech giant has said that it sees no use for personalization.

Additionally, Google told CNBC that it doesn’t make public all of the factors that make up its search ranking system because “it doesn’t want people to try to use that information to game the system.”

“It’s quite plausible that Google could just say, we know what kind of news websites you frequent, and so we’re going to prioritize them in our search results; and people might be happier that way,” says David Lazer, university distinguished professor of political science and computer sciences and co-author of the paper. “But they don’t. They tend to show diverse content, diverse choices.”

Concerns surrounding the potential for bias in Google’s systems speaks to a broader conversation about how to better regulate big tech companies at a time when misinformation and disinformation are rampant. Talk about the harms of social media companies amplifying divisive content reached fever pitch last election cycle, when a trove of information was leaked about how Facecbook’s algorithms, in particular, promoted hateful, damaging and problematic content at the expense of its users.

While the research sheds new light on how Google’s ranking system functions, researchers said it doesn’t mean that the company’s search algorithms are “normatively unproblematic.” They point out that some participants were exposed to “highly partisan and unreliable news,” noting that even “limited … exposures can have substantial negative impacts.”

“We’ve just never found this effect of Google strongly personalizing the things they show people based on partisanship,” Wilson says. “We just don’t see it.”

Those findings date back to 2013, when Northeastern researchers first began looking into the possibility of a Google Search “filter bubble.”

“In some sense, this is just the latest iteration of that same finding, but with the best techniques we have available,” he added.

“When you look at it independently, it doesn’t seem to be happening,” Wilson says. “And so that means we should probably be focusing on other kinds of problems.”

Tanner Stening is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at t.stening@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @tstening90.