A 109-year-old Japanese American film is finally getting a world premiere at the Academy Museum thanks to a Northeastern professor

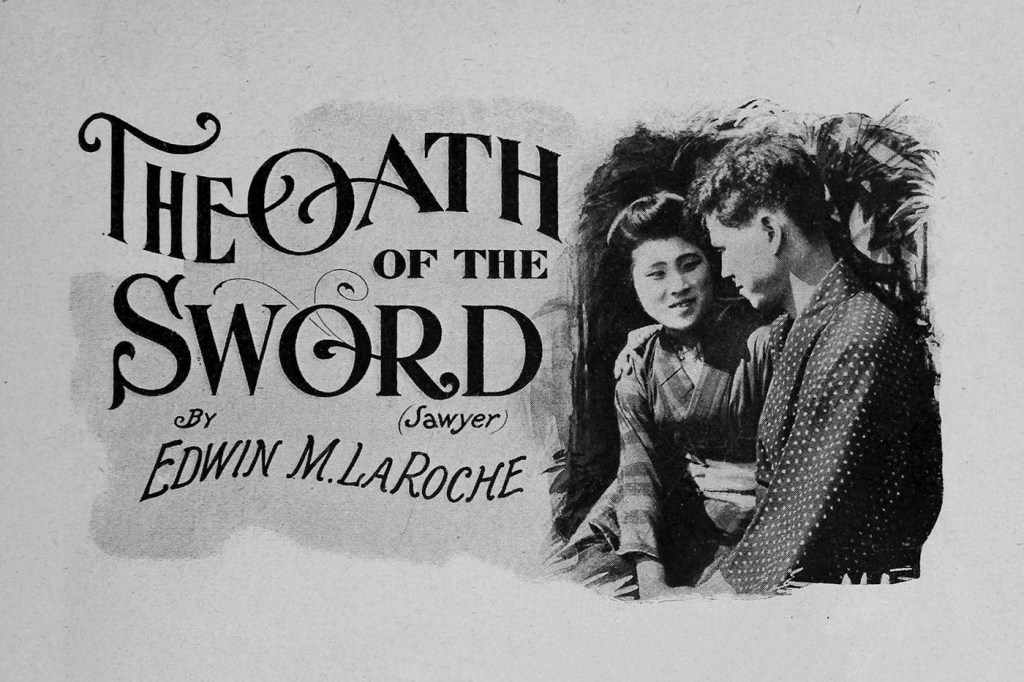

“The Oath of the Sword,” the earliest known Asian American film, never found an audience when it was released in 1914. Now, more than a century later, this historically significant silent film will, against all odds, get a world premiere at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on May 28.

For Denise Khor, the Northeastern University associate professor of Asian American and visual studies who helped re-discover the film, thinking about what this moment means is enough to take her breath away.

“This film and the films like it, these films that were made by Japanese Americans during this early juncture in American film history, never found an audience,” Khor says. “I love the idea of this film finally finding its audience in this era, 2023.”

The film’s world premiere, presented by the Japanese American National Museum, will be screened in the Academy Museum’s Ted Mann Theater, a 277-seat venue that regularly hosts special screenings of Oscar-winning films, family films and rare or historical films. The film will also have a premiere in Boston later this year.

Khor discovered “The Oath of the Sword” in the archives of Rochester, New York’s George Eastman Museum, where the original print had been stored and taken care of for decades. With a grant funded by the National Film Preservation Foundation and co-sponsored and co-written by GEM, the Japanese American National Museum and Khor, they set out to preserve this piece of cinematic history.

“The Oath of the Sword” tells the story of Masao, who leaves Japan to study at University of California Berkeley. In crossing the Pacific, he leaves behind the only home he’s known, along with his lover, Hisa. Masao finds success as a college athlete, but Hisa struggles alone back in Japan.

When he eventually returns to Japan, Masao finds that Hisa has married and had a child with a white American ship captain. The story ultimately ends in tragedy, with the captain dead by Masao’s hand and Hisa committing suicide out of shame.

Produced by the Los Angeles-based Japanese American Film Company, “The Oath of the Sword” is similar to many of the upstart Asian American film productions of this era. Khor calls it an “aspirational cinema.” The filmmakers had big dreams––they wanted to find an audience and fill theaters––but lacked the resources or distribution channels their white counterparts had.

Khor hopes the screening later this month will not only bring “The Oath of the Sword” out of the archives and onto the screen but help raise awareness about this piece of cinematic history.

The version of “The Oath of the Sword” that filmgoers see this month will be remarkably close to the original, Khor says. The original film print was too delicate for preservation work to be done on it directly, so the restored 35mm print is based on a safety print that was created in 1980. Certain elements of the film, like the title and credits, were missing, but the rest of it is miraculously intact.

The screening at the Academy Museum, which is co-sponsored by Northeastern’s College of Social Sciences and Humanities and College of Arts, Media and Design, will also be accompanied by a live performance from pianist and composer Naomi Nakanishi that will evoke the experience that moviegoers had in the early 20th century. Although this period of cinematic history is known as the silent film era, “the audience at the time never experienced it in silence,” Khor says. Movies were always accompanied by a musician, narrator or even lecturer. In Japan, these performers, known as benshi, became so beloved they were sometimes more famous than the movies themselves.

When people came from Japan to the United States, they brought that tradition with them and benshi became like “quasi-celebrities” for Japanese Americans cinemagoers as well. Khor says Nakanishi’s accompanying performance will evoke that history while also bringing it into the present, harkening back to a very different kind of moviegoing experience.

“It’s a way of staying true to the kind of medium it was and how audiences of that time really experienced the cinema,” Khor says. “Some people could see the same film, and that live performative element to it would make it a different film. That, to me, is always so wild.”

After 109 years, the fact that “The Oath of the Sword” is coming to the big screen, courtesy of the Academy no less, makes Khor hopeful about the future of film preservation work. Groups like JANM have been opening up the scope of what films are considered worth preserving since the 1980s and 1990s. Prior to that, only the work of the “great auteurs” was part of the protected film canon. But more recently preservation work like what was done with “The Oath of the Sword” has helped fill in the gaps of the silent film era, which historically hasn’t included films from people of color.

“If you think about a film like this, an independent film that didn’t find an audience in 1914 that had inadequate channels of distribution that’s run by these Japanese Americans in Los Angeles, it falls so far out of the [typical] range [of preservation],” Khor says. “[Film] is one of the only channels for people of color to be able to have access to telling their own stories.”

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.