From garage roof to racetrack, Northeastern Electric Racing drives hand-built car that tops out at 100 mph

It was a chilly November night and Matthew McCauley’s breath was billowing out in front of him when he took hold of the wheel and put pedal to the metal.

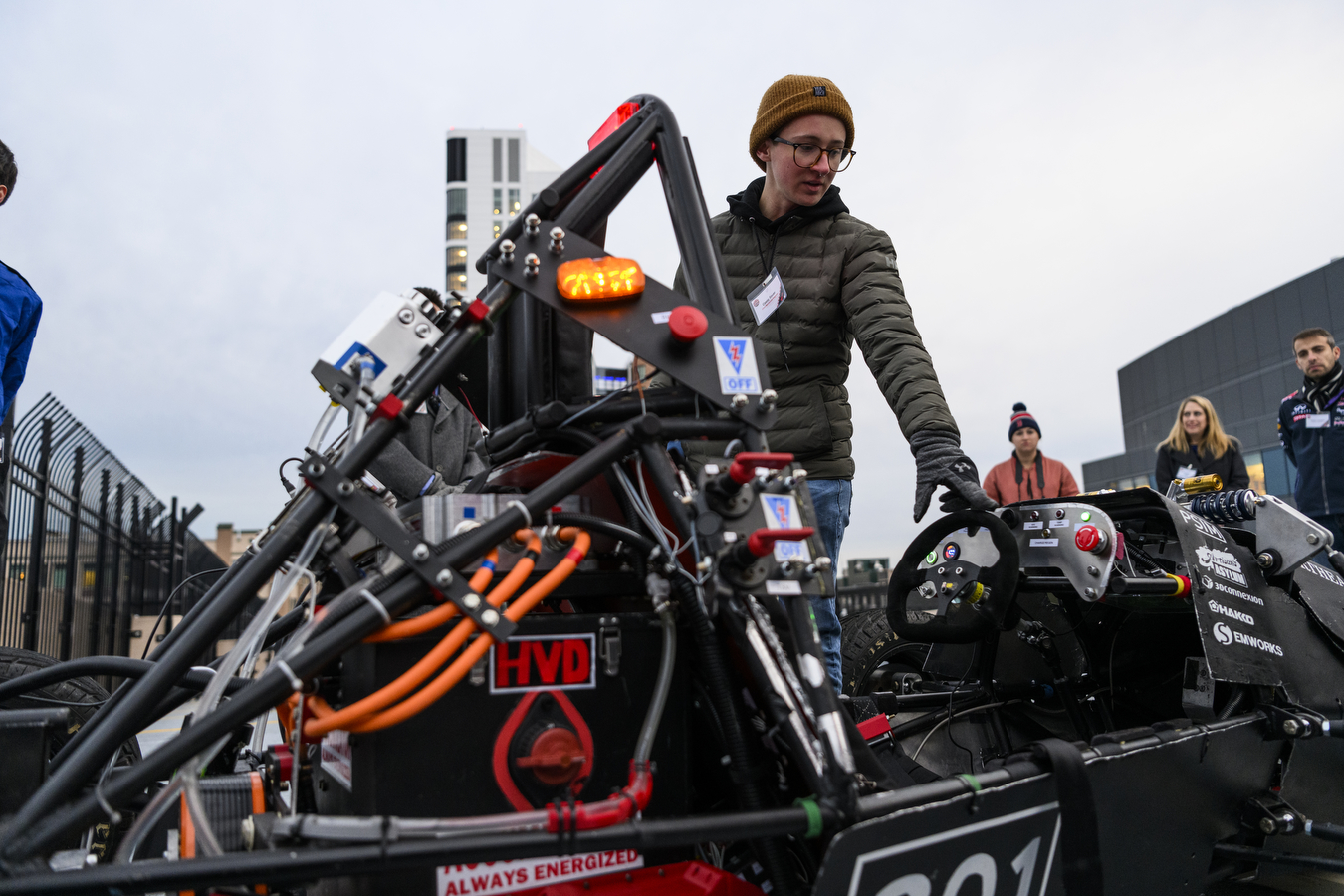

Accelerating down straightaways and taking corners with finesse, it’s easy to forget McCauley, in his blue racing jacket and jet black helmet, is racing laps around the roof of Columbus Parking Garage on Northeastern’s Boston campus. But that’s the reality of Northeastern Electric Racing, a student club that has made due and found massive success in the world of electric racing despite its relative rookie status.

McCauley, NER’s chief electrical engineer, has seen the club’s car, Cinnamon, go from a 5-foot drive test to hitting 60 miles per hour in competitions.

“It’s a go-kart that has 110 kilowatts of power, 109 kilowatts of power,” says McCauley, a fourth-year electrical and computer engineering student. “That’s over 100 horsepower.”

Because of November temperatures, the power level on display during a drive day event on Tuesday was less than 50% of the car’s full capability, McCauley admits. It was more than enough for President Joseph E. Aoun and Northeastern administrators to take a test drive, but at its best Cinnamon is capable of hitting a max speed of 100 miles per hour.

After the drive day, NER plans to completely disassemble the car to install several upgrades, including a thermal management system. That’s the story of NER throughout its relatively short five-year history: Perform, upgrade, then hit the road again.

NER competes in Formula Hybrid+Electric, an annual engineering competition held at New Hampshire Motor Speedway that pits teams of undergraduate and graduate racing teams against one another. NER competes in the full electric category, which has hit new levels of popularity alongside Formula E, the professional electric racing circuit that launched in 2014 in partnership with Formula One, and electric automakers like Tesla and Rivien entering the mainstream. Despite its relative rookie status in the world of electric racing, NER hit the ground at high speeds, taking second place in New Hampshire last year.

James Chang-Davidson, president of NER and a fourth-year computer science student, is proud of how far the club has come in just five years. He remembers when the club was “just a couple guys working on some metal.”

“I’ve seen the team go from a small team of engineers, maybe just about 25, 30, 40, all the way up to now where we have over 200 active members across 11 different teams and a really strong team atmosphere building the car, building software and growing the team to learn all these different skills,” Chang-Davidson told a crowd of Northeastern administrators and NER sponsors and members during the event.

The team NER has assembled stretches across the university’s Boston campus, from the College of Engineering and Khoury College of Computer Sciences to the D’Amore-McKim School of Business and College of Arts, Media and Design. Most of the students in NER have never worked on cars before. Success comes from team members working together to bring their own perspectives, skill sets and enthusiasm to a truly collaborative challenge.

“Working on a team like this, we are extremely heavily emphasized that you don’t need any background, any experience, any skill level really coming in,” Chang-Davidson says. “It’s all about your willingness to participate and contribute and be involved in what’s going on.”

Cinnamon is NER’s first car, but it’s experienced a few face-lifts over the years. It’s been a steady process of designing, prototyping and testing to get to this point. The steering wheel alone went through at least 12 different iterations. But the crown jewel of the car is the battery, a completely custom piece of technology.

The battery is made up of 504 lithium ion cells, each one twice the size of a AA battery, that students had to source from scraps pulled from battery packs. McCauley says that for NER’s next car, which will be ready for competition in 2024, Tesla has already donated 1,000 cells to help power the vehicle.

The event this week was an opportunity for NER to showcase the countless hours of work it has put into its electric race car, but Catherine Kennedy, president of NER, says it’s also a chance to emphasize the importance of moving toward an electric future that relies less on gas-guzzling vehicles.

“Major manufacturers are now pushing towards it, and it’s just the infrastructure that’s catching up more than the tech because obviously charging an electric car is currently more difficult than getting gas at a gas station,” Kennedy says. “But the hope is that that will change.”

The club is also looking to its own future. With its second car, the club hopes to transition from the Formula Hybrid+Election competition to Formula SAE, a larger design competition that has both national and international reach. Chang-Davidson admits “pipe dreams are my thing,” but, as he nears the end of his time as club president, he says he has high hopes for NER’s future.

“I want to see the team continue to develop, because we’ve been told that we have the level of organization that rivals many companies,” Chang-Davidson says. “I want to see us be able to challenge on the national stage, challenge on the international stage and ideally get to that point where we can be one of those teams breaking world records, but, like I said, pipe dreams.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.